Articles and Features

Out of Touch and Out of Time – Fame, Delusion and the Lesson of Christian Rosa

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Volume 19

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in a recent standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

Christian Rosa is a Brazilian-born, Austrian-raised abstract painter who hit in 2013. The craze for his work and the impassive millennial machismo around it — like Sterling Ruby, or Jonas Wood, or Oscar Murillo, or Eddie Martinez — was energetic and bracing. It was muscular, ostensibly risky but ultimately certain work that picked people up. That energy is part of the story of the newly perky, recovering art market of the 2010s. This column is about Christian Rosa’s demise in 2021, and the sickness of delusion that threatens a successful artist.

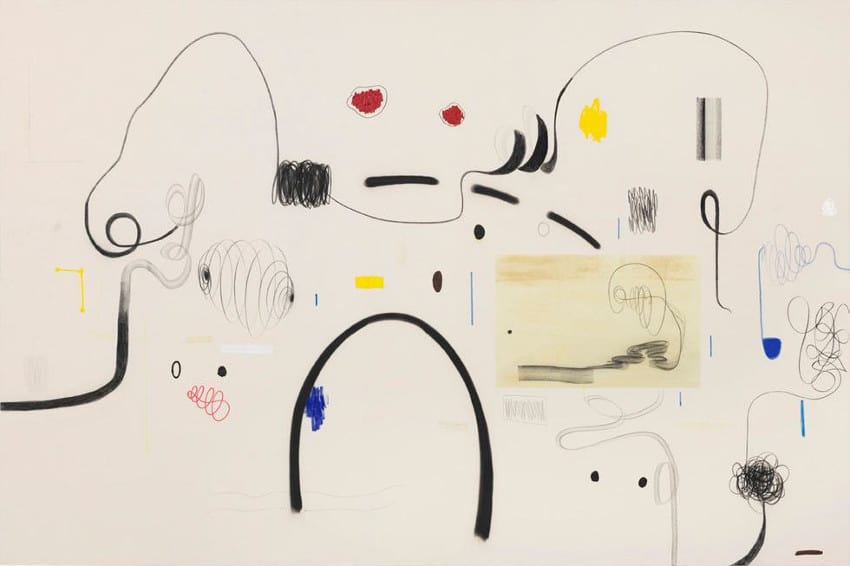

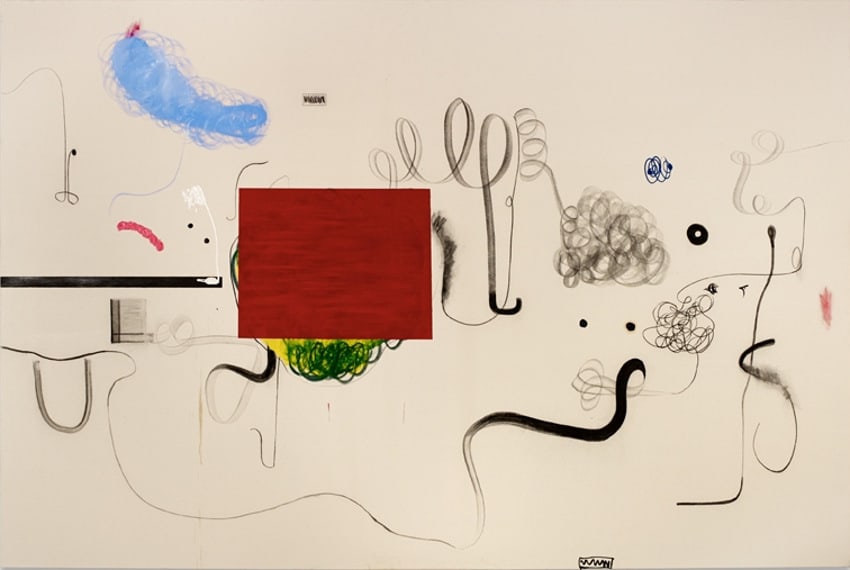

Rosa’s paintings were gigantic blank canvases filled with an executed bare minimum of information. They were lyrical doodles, akin at times to graffiti, to graphics, to the core units of geometric modernism around Joan Miró. They were at times automatic or unconscious, in the realm of ideas fully staked out a hundred years ago in Paris. Scrawls and squiggles and shapes. Comparisons to Cy Twombly were, let’s be honest, a bit of a reach. Rosa’s paintings weren’t bookish or even particularly literate. They were impulse.

The creation of his paintings was all about flow, a skimming over creation. Transitions from sequence to sequence, stringing things together. Make the wobbly line go into the blob, then balance it with the other blob. Fill this amount of space in this amount of time. Figure it out. He was not good at talking about his paintings. It was either low-dose bromides, talking balance and inspiration and poise, or near-meaningless description. “For me it becomes easier to do a long stroke than to do small lines,” says a pull quote from a 2017 feature for an online lifestyle site. “It feels more natural to do bigger strokes.” This was the best stuff on the tape, I guess, after he did his requisite bit about how he met his friend Leonardo DiCaprio.

Depending on how real you saw him to be — I have never met Rosa, so can’t say — this mentality of dogged presence, the eternal now, could almost be justified as a religion and a total lifestyle. In his image and on the canvas he sold the character of a fully qualified bad boy, taking risks, figuring stuff out as he went. Life and painting according to Christian Rosa was about thinking on your feet, knowing when to pivot, knowing when to stop, knowing when to keep it moving. His thinking was reactive and relative, all in the name of staying in the moment, being of the moment. Punk, basically. Not being told what to do. Trusting yourself.

Rosa’s thing lasted only a few years. He came out super undercooked and that was always going to catch up with him. He made a lot of noise in a short space of time and hit his marks around the world, hoovering up the loot of local collectors. Good-looking guy getting his picture taken. He shut down Berlin Gallery Weekend in 2014. Christie’s hit a wild record price for a painting. An airless, slightly sad 2015 exhibition on the ground floor gallery of White Cube’s spaceship in London’s Mason’s Yard suggested that Rosa could not continue a pantomime of greatness. People with short attention spans moved on. Flippers and speculators and investment bros hung Rosa out to dry. A few wacky, cruel auctions torpedoed his market. That’s all it takes, and that was that. This happens all the time, especially in today’s fast and trendy financialized art market. This happened to a lot of artists. And for that reason, I hadn’t thought about Rosa in five years. If pressed, I would have guessed that he’d bought a house and was doing fine. And then he came back.

This past January, in an Artnet News scoop of such quality that reporter Nate Freeman has since landed a Dominick Dunne spot at Vanity Fair, we learned of bad, obviously wrong Raymond Pettibon works that were going around the back channels of the secondary market. They looked unfinished, altered, far from official. Rosa was tangled up in this hot merchandise; everything led back to him. Rosa had painted on unfinished Raymond Pettibon wave drawings, likely purloined or — even worse — gifted from Pettibon, who he knew well. He’d sold four of them by the time the scam fell apart. He even forged certificates of authenticity. Fairly large sums of money were involved in these extremely illegal deals. It was a scandal. The plot thickened in October, when the FBI issued a ferocious statement urging Rosa to face justice. Rosa had slipped out of the country while the story was still coalescing this spring. Outrageous emails came out from the final days, in which Rosa impaled himself repeatedly, blurting out his criminality alongside ‘bummer dude’ shrugs. Last weekend, Freeman broke the news that Rosa had been fingered by the feds in Portugal, and is in the process of being extradited back to the US.

That’s where we’re at. Rosa might go to jail; the identity theft charge has a two-year mandatory minimum. Art people can go to jail. Mary Boone, one of the biggest New York dealers of the ’80s, just got out of jail, she did 13 months. He might get off. Some people are out some money, which they’ll probably eventually get back now that Rosa has been apprehended. Nobody got killed. This hasn’t hurt Raymond Pettibon’s career, he has a good team insulating his reputation from this nonsense. And Rosa’s act of desperation and overreach may fade into Americana, LA dark folklore, like John Holmes or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. This whole thing may ultimately be better remembered in the society pages than in the police blotter and as something more poetic than evil.

I want to remember something else about Rosa’s dumb hustle, however, and that’s that it’s a madness. This is important. The laissez-faire philosophy of Christian Rosa says “take it as it comes.” Take a surfer’s eye at the canvas, adjusting to the breaks. This elevated perpetual nowness is charismatic, it sparkles. But it is not strong, as the Pettibon scam proves. Rosa’s provisional, passive reality drifted to the point where he, nominally a punk, tried to rob from a punk mentor, and then rob someone else. How do you get to the point of thinking that was a good idea? How do you square that with your supposed identity, your supposed values? Relativism doesn’t work for everything. It is important to have anchors in your decision-making, certain philosophies or traditions that keep you away from some dumb hustle. It is important to have principles in your practice because without them you’ll have no idea what you are doing. Without them, you’re not making art.

This is the final Standards & Practices column, and it might sum up the voice of this project pretty well. Being an artist or an art lover means looking closely and sticking at it, because being serious and working hard is the answer. It’s harder than being Christian Rosa, but you’ll get more out of it. If you have enjoyed S&P, thank you for sharing the past two years with this moral narrator, and if you are a new reader, please enjoy the archives. We’re starting a new column next month.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol. 14: A Mellowing Dictator. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jonathan Meese

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol. 15: Yours For the Taking: Justine Kurland’s Continuing Story of Freedom in America

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol. 16: Cooler Heads. Yue Minjun and the Lessons of the Recent Past

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol. 17: New Thoughts on Ugliness. Information, Visualisation, and Hans Haacke’s Dream

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol. 18: Tell Me Everything: Honesty in the Art World, the Armory Show, and the New Work of Richard Prince