Articles and Features

The Fear Of Art: Contemporary Art Censorship

By Adam Hencz

Tampered photographs, removed paintings, destroyed sculptures, detained artists, and silenced opinions. Censorship is the most common violation of artistic freedom.

Contemporary art and artists are unduly censored due to their creative content, which is opposed by governments, political and religious groups, social media platforms, museums, or by private individuals. Artists and advocates of artistic freedom are often silenced for questioning social and religious norms or expressing political views that oppose dominant narratives. Even so, regardless of the censors’ rationale behind removing or oppressing art, their actions potentially justify its meaning even more.

Reality has always been, from the beginnings of artistic expression, an essential vehicle for creation. The depiction of what the eyes see, and what humans feel and think, is one of the main themes for art. Nevertheless, artistic production never solely replicated reality —even during Realism it had its purpose of showing the brutality or beauty of everyday life to viewers— and neither has art ever been just a personal reflection of an artist, unengaged from the world. Its interpretation is confounded within a web of contextual meanings, exposing it to vulnerability when forced into an artificial context.

Museums

Recent acts of art censorship in museums, against works or exhibitions from renowned artists, have been interpreted by many as proof of dangerous political correctness and total disregard of the value of the pieces. Works of artists from the 19th and 20th centuries were recently deemed offensive either by museums or the public and consequently removed from display. Among others, the Manchester Art Gallery took down John William Waterhouse’s painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1896); Egon Schiele’s centennial exhibition advertisements suffered censorship in London and Germany; and, on the occasion of the show Balthus: Cats and Girls – Paintings and Provocations, a petition was signed by many to convince New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to control the way people look at Balhus’ Thérèse Dreaming (1938).

Museums were established to protect artistic freedom and defend the right of art to shock and unsettle and defend the right of the viewer to be unsettled. However, institutions also tend to censor works of art on political grounds and stimulate debates. The recent case of postponing Philip Guston’s retrospect which was scheduled to be opened in 2020 shows clear implications for the involved museums. The reasons for the postponement had little to do with Guston’s work itself and much more to do with the institutions’ lack of faith in their curators and lack of belief in the intellect of the general public’s ability to navigate the subtleties of Guston’s oeuvre. The cancellation caused a backlash from the artistic community and locked the museum world in a heated debate over race, self-censorship, social justice, appropriation and ‘cancel culture’.

Governments

Dominant forms of political narratives polarise us around the world and leave no mercy to theaters, novelists, museums and musicians who find themselves under attack for being critical of the government and governing ideologies. Forms of nationalism – or religious nationalism – have been used in Poland and Hungary, but also in India, where governments institutionalised religious bodies play a growing role in determining what is deemed appropriate in the public space. This tendency adds to the growing global trend of underfunding culture to make it vulnerable. The appointment of unprepared and unprofessional persons in key cultural positions has thus become a systemic issue.

As the largest independent international organisation defending freedom of artistic expression Freemuse reports, the Turkish, Russian, and Chinese governments abuse counterterror laws against artists, who therefore face censorship, harassment, threats, or imprisonment, accused of being close to terrorist groups or because their artwork was interpreted as a threat to the nation. The case of Turkish artist and journalist Zehra Doğan sparked media attention from human rights advocacy groups and arts communities in 2017 when she was sentenced to two years and 10 months.

She was jailed, together with her work as a journalist, for a painting depicting a town in the majority-Kurdish south-east of the country that was destroyed in a Turkish military operation in 2015.

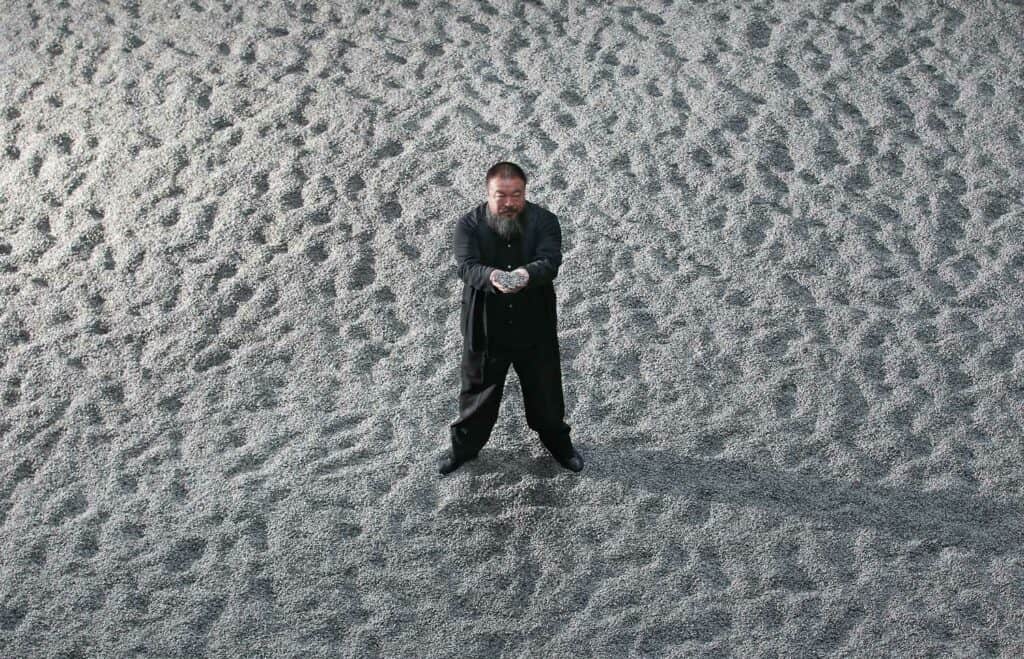

Ai Weiwei is an artist who today is known not only for his art and activism, but also his crusade against the Chinese government. Ai Weiwei uses his creative work as a vehicle to speak out against censorship, the gentrification of the art market, and to criticise China’s ruling government. In 2011 he was detained after police had searched his studio, confiscated computers, and questioned assistants. Shortly after his 81-day detention, followed by four years of de-facto house arrest, his studio in Shanghai was demolished. However, the demolition appeared to be a byproduct of Beijing’s latest urban development plans, even though it is still widely believed to be in retaliation for the artist’s criticism of the government. In 2014, days before the government-operated Power Station of Art in Shanghai was to stage an exhibition devoted to the winners of the Chinese Contemporary Art Award, officials in the city dropped his name from the artist list —removing his renowned work Sunflower Seeds from display— due to his outspoken criticism of systematic censorship.

“In the end, those who seek to censor and destroy art testify to its power, whether the work is seen as a symbol of something hated or disliked, or simply as a vessel of form.”

David Freedberg

Every act of censorship is related to a larger pattern of pressure being brought against education, the press, film, and the freedom of speech. These efforts cast a shadow of fear on the public that leads to voluntary curtailment of expression by those who seek to avoid controversy and eventually fail to provide clues to the social use and function of images. However, it is key to keep David Freedberg’s words in mind during the clashes between artistic freedom and forms of silencing, that “in the end, those who seek to censor and destroy art, testify to its power —whether the work is seen as a symbol of something hated or disliked, or simply as a vessel of form”.

Relevant sources to learn more

Find more cases in Freemuse‘s The state of artistic freedom reports

Censorpedia: An Interactive Database of Art Censorship Incidents

10 Controversial Art Pieces That Shook the Art World