Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The Ninth Street Show

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider the history of art exhibitions themselves? Landmark shows of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices.

For this week’s edition of ‘The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History’ series, our focus shift back to the Big Apple to examine the exhibition that would definitely establish New York as the global capital of the art world: the 1951 Ninth Street Art Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture – also come to be known just as the Ninth Street Show.

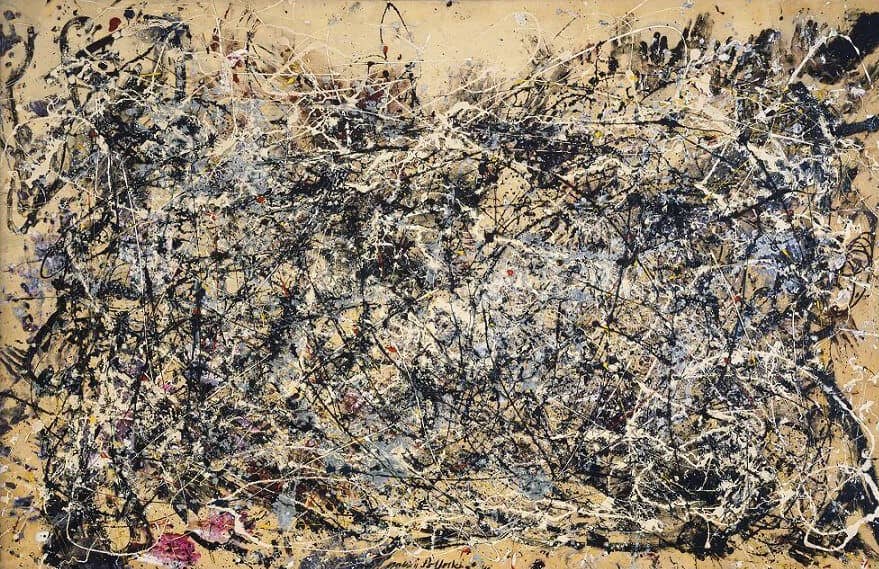

Thirty-eight years after the introduction of European Avant-garde to a dumbfounded American audience by the Armory Show, this pivotal exhibition marked a fundamental step in the path of American modern art, launching the first specifically American movement to achieve international resonance, Abstract Expressionism.

The background

By the 1930s, the New York art scene began to be further exposed to European modernism. On the one hand, prestigious institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Non-Objective Painting — soon-to-be Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum — opened their doors, respectively in 1929 and 1939. On the other, following the French and British entrance into World War II, European artists and intellectuals sought refuge in the United States, where modernist ideas found renewal and opened up new possibilities. Among them were leading Surrealist figures as Dalí, Ernst, Breton, but also celebrated Cubists and abstract artists – Mondrian, Chagall, Léger, and many others.

Inspired by many aspects of the European Avant-garde – from the Surrealist interest in the unconscious to the emotional subjectivity of German Expressionism – young American artists shifted the art world’s focus towards abstraction, developing several individual styles of painting today pigeonholed into the Abstract Expressionism movement. However, they also felt intimidated by the arrival on American shores of such iconic artists, and, united by the desire for a style that was uniquely American, began to organise informal gatherings around the vibrant Greenwich Village to discuss modern art.

This loosely affiliated group of radical artists – and intellectuals too – belonged to the so-called New York School and, mostly revolving around the 8th Street Club, soon began to be known also as ‘the Club’.

Although ‘the Club’ was the centre of the intellectual life in post-war New York, their work was too radical and in opposition to both the market trends and the general taste to be showcased and recognised by museums and galleries. The Ninth Street Show would mark the turning point in the emergence and ultimate acceptance of Abstract Expressionism, the definitive breakthrough in the development of quintessential American modern art.

The show

When thinking of art shows that went down in history, one may envision exhibitions planned to perfection by esteemed curators in fancy venues; this was not the case with the Ninth Street Show. The story goes that after a night out, the painter Milton Resnick came back home to his partner at the time, fellow artist Jean Steubling, and, befuddled by alcohol, began complaining about his miserable career as a struggling artist. Tired of such self-pity, Steubling took over the situation and dealt with the owner of an abandoned building nearby, at 60 East Ninth Street in Greenwich Village, thus securing a space to house an extemporary art exhibition.

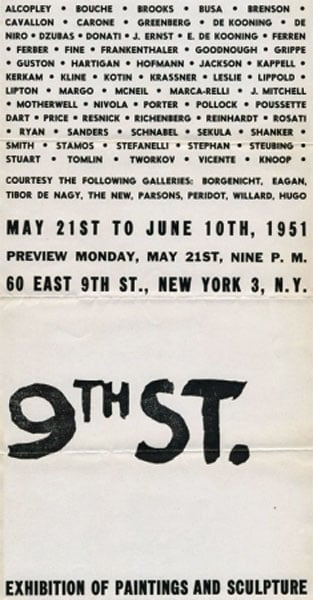

Leo Castelli, fledgling art dealer of Italian origin – as well as one of the very few non-artist members of the Club – hung the show as his first American curatorial effort, also investing in the event by covering the expenses: $70 for the rent, plus the cost for paint and repairs. The artists did all the rest. From transforming the rather decrepit venue – the building would be demolished shortly after the show – into a makeshift art gallery to designing the promotional materials for the event, including the historic poster that gave the show its name.

The Ninth Street Show took place in the ground floor and basement of the building for three weeks, from May 21 to June 10, 1951, and featured the work of seventy-two artists, of whom only around sixty are mentioned in the poster.

With the exception of a few painters, such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, that were already legends in the underground art scene, the others shared the same condition as Milton Resnick, always seeing their work unrewarded and rejected by art institutions due to its radical nature. Struggling to gain critical recognition, none of them wanted to miss the opportunity to exhibit their art, and the rush to join the exhibition reached the point that each artist was limited to a single piece.

The majority of them would remain unnoticed and never achieve the coveted acclaim; Steubing herself abandoned the art world entirely; others left the city. However, a handful of those then little known artists gained increased recognition, and today their names sound instantly recognisable as the ones belonging to the most illustrious proponents of American painting; among them, Robert Rauschenberg, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell.

Apart from some pictures taken by Aaron Siskind, member of the New York School himself, not much documentation of the show remains to date, neither a catalogue nor a list of artworks displayed, a fact that arguably has conferred an aura of myth to the Ninth Street Show, making this hastily arranged exhibition the stuff of legend.

The women of the Ninth Street Show

If it is true that the New York School struggled to gain critical recognition, this is even more so for its female members who, in addition to the challenges presented by cultural institutions, had to face the obstacles posed by society.

The Ninth Street Show, even if extremely radical in some respects, did not dismantle the chauvinism of the time. On the contrary, initial discussions addressed the issue of whether featuring women artists in the exhibition would have reduced the chance of being taken seriously.

Eventually, out of seventy-two participants, only eleven were women. Besides being outnumbered and often overlooked, their work has been often belittled by considering it only by reason of the artists’ status as women rather than their talent and personal artistic research. Tired of the persistent sexist comments, when asked if a male artist ever told her she painted as well as a man, Grace Hartigan once replied sharply: “Not twice”.

Some of these eleven artists have never the less found their rightful place in the contemporary art pantheon – despite being overshadowed by their celebrated artist-husbands for most of their lives. This was, for example, the case of Elaine De Kooning, married to the more famous Willem, as well as for Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner. The latter, most passionate advocate of her husband’s genius, prioritised his work over her own ambitions to the point that her career only flourished after Pollock’s death in 1956. Yet, she once stated in self-admission: “I’m always going to be Mrs. Jackson Pollock – that’s a matter of fact – but I painted before Pollock, during Pollock, after Pollock”.

Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, and Joan Mitchell have also received international recognition, as well as Perle Fine and Anne Ryan, on account of their idiosyncratic interpretations of Abstract Expressionism.

Others have remained rather unknown, like sculptor Day Schnabel, and poet and painter Sonia Sekula. But this is arguably bound to change.

In fact, the last decade has seen a couple of retrospectives re-examining the impact of all these artists and giving them the well-deserved attention: the Denver Art Museum’s show Women of Abstract Expressionism in 2016, and Sparkling Amazon: Abstract Expressionist Women of the 9th St Show, held at the Katonah Museum of Art in 2019.

Moreover, in 2018 acclaimed writer Mary Gabriel published Ninth Street Women, a chronicle of this pivotal exhibition’s protagonists, which is also being developed as a television series production to show the general public how did these talented artists have positively impacted the course of art history and tear up the prevailing social code, challenging at once the aesthetic and the social status quo – at times at a high cost.

Recognition and Legacy

With hardly any artwork sold, the Ninth Street Show did not exactly correspond to the traditional idea of success; nonetheless, it was deemed as a real breakthrough as it reached the goal of drawing the interest of a sceptical audience, especially art critics and gallery owners. Soon Abstract Expressionism received praise from curators, critics, and collectors, figures of the calibre of Alfred H. Barr, Clement Greenberg, and Peggy Guggenheim. As Bruce Altshuler commented, “It appeared as though a line had been crossed, a step into a larger art world whose future was bright with possibility”.

Following the exhibition, the artists continued to organise the Art Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture as a yearly event at the uptown Stable Gallery from 1953 to 1957.

The Ninth Street Show is now regarded as the launch of Abstract Expressionism but it has also been pointed out how its spontaneous character represented the celebration of an active artistic community – rather than a painting style.

As a symbolic twentieth-century counterpart of the Salon des Refusés, artists united by communal spirit overstepped external recognition by official institutions to expose and promote their art. A venture that resulted in the ultimate shift of the centre of the art world from Paris to New York.

Relevant sources to learn more

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

The Salon Des Refusés

The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’

The Armory Show

Nazi Censorship And The ‘Degenerate Art’ Exhibition of 1937

The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938