Articles and Features

Pioneer of Space – Alexander Archipenko’s Spatial Cubism

By Shira Wolfe

“Traditionally there was a belief that sculpture begins where material touches space. Thus space was understood as a kind of frame around the mass. (…) Ignoring this tradition, I experimented, using the reverse idea, and concluded that sculpture may begin where space is encircled by the material.” – Alexander Archipenko

Boundary-breaking sculptors are those, who in his or her own way pushed the medium of sculpture forwards into new, unique territories. Last edition featured one of the pioneers of modernist sculpture, Constantin Brancusi. This week, we discuss the work of Alexander Archipenko, one of the first artists to apply the principles of Cubism to architecture.

Alexander Archipenko – A Ukrainian in Paris

Born in Kiev in 1887, Alexander Archipenko was one of the many artists born in the Russian Empire to move to Western Europe. He left his home country, today known as Ukraine, in 1908, pursuing a specific aim in his artistic practice: to depict modern life in revolutionary ways and discover new modes of abstraction. Between 1910 and 1920, he lived in Paris, where he became part of the avant-garde circle and cultivated a distinct visual language, becoming one of the first artists to apply the principles of Cubism to sculpture. Between 1910 and 1914, dance became a prevalent theme in his sculptures. At the time, dance was a symbol of modernism, and also a place for the creative investigation of body, space and movement, all topics of interest for Archipenko. In his sculpture Dance from 1912, Archipenko creates a dialogue between bodies and space, as two dancers embrace an immaterial zone. He wrote the following about this piece: “In another experiment I encircled space with the material forms of two figures.”

The Materiality of the Non-Existent

Archipenko’s understanding of spatial volumes can be traced back to his childhood. He spoke of watching his parents place two candleholders next to each other, which created a third, inverted form in the negative space. Another source of influence was the Chinese philosopher Laozi, who described the importance of immaterial space. It was this “materiality of the non-existent” that became a fundamental notion for Archipenko. Previously, the conventions of sculpture had demanded that figures be represented in mass. Archipenko was after something totally different – he began to replace solid volume, such as heads and torsos, with voids. Yet, in line with the philosophy of Henri Bergson, who was greatly beloved in avant-garde circles of the time, Archipenko did not regard the non-existing shape as an actual void, but rather as a symbol for the missing form which cannot be materialised and is retained purely in memory. As such, the absent form was imbued with great creative potential.

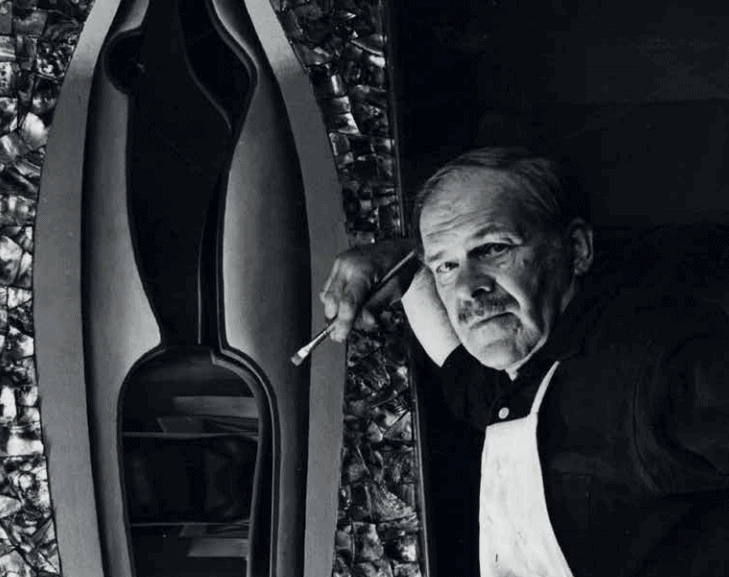

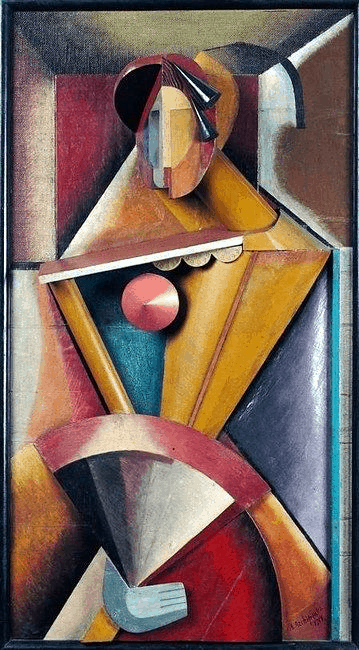

Sculpto-Paintings

An important element in the artistic practice of Archipenko is his sculpto-painting, a special type of fusing painting and sculpture which earned him the title of “spatial cubist”. For his early sculpto-paintings, made during his time in Paris, Archipenko mostly used concave and convex shapes that he painted polychrome in order to create illusions and dissolve spatial boundaries. Archipenko revisited the sculpto-painting again in the 1950s, this time with a more organic and curvilinear approach and using more contemporaneous materials.

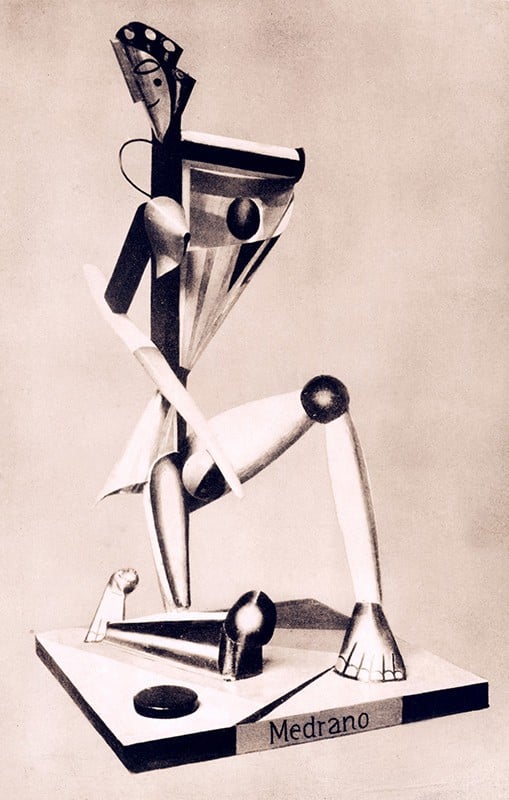

Movement in Space

In the 1910s, Archipenko made a significant breakthrough, introducing actual movement into his sculptures. In 1912, he implemented this in his construction Medrano, assembled from glass, wood and metal, which had an adjustable arm. Next, he made Woman Walking (1912-1918), a dynamic female figure that suggests forward motion. For Archipenko, immaterial space was a virtual form that represented universal change and spiritual energy. He was sculpting motion, space and time.

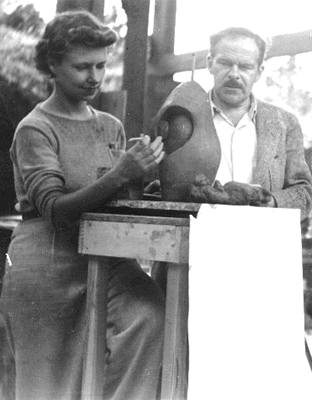

Berlin – Time, Space, Movement and Light

In 1921, Archipenko married German sculptor Angelica Forster, and the couple relocated to Berlin. During his time here, Archipenko became part of the vibrant artistic community and connected with the Eastern European avant-garde, including László Moholy-Nagy, with whom he shared an interest in topics surrounding the integration of time, space, movement and light.

“Sculpture must have a significance beyond its form to become a symbol and produce association and relativity fixed by stylistic transformations. This sublimates the sculpture into the metaphysical realm. This is the mission of art.” – Alexander Archipenko

Constant Developments – Archipenko in the United States

Archipenko moved again in 1923, this time relocating to New York, where he opened an art school (as he had previously done in Paris and Berlin) and started the annual summer art program in Woodstock, NY, which continued until his death. Though he initially struggled with the immigrant life in New York, receiving far less recognition than he had enjoyed in Europe, he continued to expand on his ideas and worked and taught extensively across the United States.

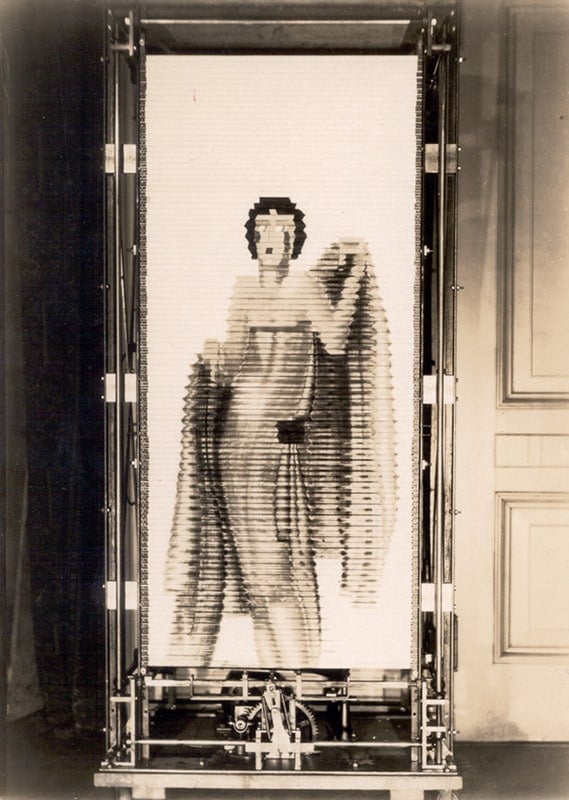

In 1927, Archipenko patented Archipentura, a mechanical system for applying paint to small strips of canvas that could be moved to create a complete image. Art, Archipenko believed, should reflect the dynamism of modern life, and this invention was a natural extension of his philosophy.

In 1936, Archipenko was included in the MoMA exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, and in 1937, upon invitation by László Moholy-Nagy, he moved to Chicago to teach at the New Bauhaus. The last decades of his life were spent mostly based in New York, while teaching and lecturing around the country and experimenting with new industrial materials such as Formica and Bakelite. He used these materials for his sculptures and sculpto-paintings of the period, works that were often brightly coloured and ambitious in scale. It is important to note Archipenko’s penchant for using colour in his sculptures, since historically, colour was not commonly used by artists working in the medium.

Archipenko died in 1964 in New York, leaving behind a vast legacy and having just published his book Archipenko: Fifty Creative Years, 1908-1958 in 1960. The last work he ever made was King Solomon (1963). Fittingly, this was also the only piece that he ever conceived as a monumental sculpture. Abstract shapes come together to create the figure of the king, with tall prongs suggesting a crown and the intersecting triangles evoking an imposing costume.

Relevant sources to learn more

For other boundary-breaking 20th century sculptors, see: