Articles & Features

Life by Design: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Iconic Style

By Tori Campbell

“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way – things I had no words for.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

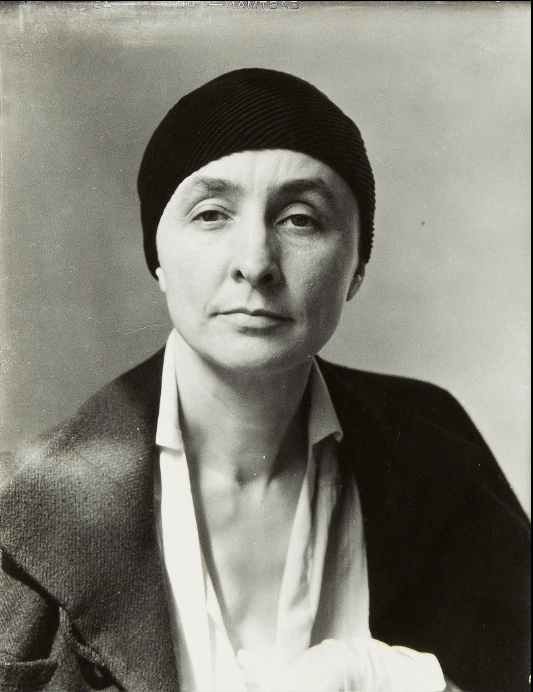

Though often recognised as the “Mother of American modernism” Georgia O’Keeffe spent much of her life intentionally downplaying her femininity in public in order to be taken seriously as an artist. Aware that perceptions of her as a person would inform her audience’s reception of her work, Georgia O’Keeffe’s style was carefully crafted to form a coherent picture of the woman she wanted us to see.

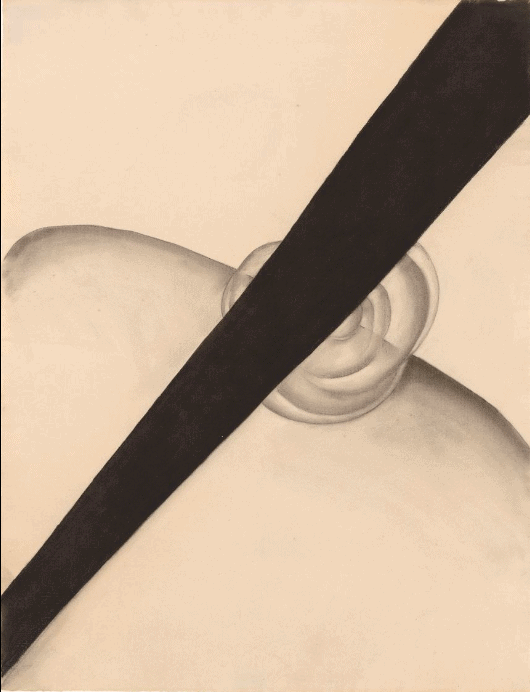

Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 2003.01.006. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In 2017, guest curator and art historian Wanda M. Corn put together the exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern at the Brooklyn Museum: a phenomenal collection that explored how, through looking at her clothing and objects, not only her artwork, we may be able to understand Georgia O’Keeffe, the woman.

“There’s something about black, you feel hidden away in it.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe: Early Life

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe was born in 1887, to a late-Victorian family from which she learned to draw, paint, and sew from a young age. By 1905, O’Keeffe had begun her formal art training at the Art Institute of Chicago, later moving to study at the Art Students League of New York. In 1908, she took up teaching in order to make ends meet financially and continue to live away from home and outside of the watchful eye of her family.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

During this time, O’Keeffe studied art during the summer and was introduced to the work of Arthur Wesley Dow, who focused more on personal style and interpretation rather than representation. O’Keeffe’s style was heavily influenced by this discovery, and she crafted arresting charcoal drawings that grabbed the attention of art dealer and photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Personal Life

In 1918, Stieglitz offered O’Keeffe the financial backing for an apartment and studio space in New York City. Their relationship quickly turned personal, and Stieglitz moved in with O’Keeffe while they also worked together professionally. It was early in their relationship, and before their tumultuous marriage, that Stieglitz would take and exhibit deeply sensuous nude photographs of O’Keeffe.

These works, though only a small portion of the portraiture that Stieglitz would capture of O’Keeffe throughout their lives together, would end up deeply affecting O’Keeffe’s own work. Her abstract paintings of flowers, rendered from an extremely close perspective, are often compared to female genitalia and women’s sexuality – an intention that O’Keeffe would deny and come to resent (though Stieglitz encouraged these rumours of representation). O’Keeffe would be the subject of over 300 portraits by Stieglitz but, perhaps because of this loss of control over her own work or the overt sexualisation by her photographer and lover, O’Keeffe would only very rarely reappear nude again.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Style

A fairly minimalist dresser from her youth, O’Keeffe truly embraced a black-and-white palette all-but-devoid of ornamentation when living in New York City from the 1920s to 1930s. This was in stark contrast to the rich colours adorning her paintings of skyscrapers and flowers, and it has been thought that she clothed herself with the photographer’s lens in mind.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Indeed, the architectural composition of her body, while she stares directly into the lens, leads us to believe that she knew the power of knowing how to be photographed. Additionally, the lack of colour involved in her dress would translate well in Stieglitz’s black and white photographs, and O’Keeffe’s playfulness with proportion turned her body into a modernist canvas.

Her boxy, white blouses (often made by her own hand) in contrast to her more fitted black suits showed her awareness of scale and form, and she was clearly just as meticulous about the clothing that she purchased. The Brooklyn Museum exhibition displayed rows upon rows of the same shoes in multiple colours, illustrating that once O’Keeffe found something that suited her in both fit and function, she was a loyal devotee to that style, creating the sense of the cohesion and coherence which is central to modernism.

O’Keeffe was also an avid collector of kimonos, found both in the United States and abroad, adopting a popular wave of ‘Japonisme’ at the time. Though her obsession could arguably be seen as appropriative at worst, and touristic at best, the silhouettes of the garments had a great impact on her personal style as both the utility and form of the kimono well suited her minimalist and modernist personal aesthetic.

Her appearance was often affected by her immediate surroundings to the point that, in her later years, after Stieglitz’s death and O’Keeffe’s move to New Mexico, her style changed accordingly.

Bruce Weber and Nan Bush Collection, New York. © Bruce Weber

In response to the surrounding Southwestern topography, O’Keeffe’s clothing took on a self-referential approach with her take on a modern, artful cowgirl, echoing the colours and sensibilities found in desert landscapes. Notably, at this time she was no longer being photographed by Stieglitz, but by younger photographers who sought to capture her as the icon of American modernism that she had become to be known as: a world-renowned artist and a woman who was thoughtfully in control of how she was seen and perceived.

George F. Mobley/National Geographic Creative

O’Keeffe led a complex and vibrant personal life, one that could take years of study to understand. However, by exploring her style and how she chose to present herself to the world, we can begin to see how she became a true icon of modernism in every sense: from her art, to her clothing, and her performance.

Relevant sources to learn more

Hear curator Wanda M Corn talk about the exhibition and meeting O’Keeffe on The Great Women Artists Podcast — and find more art podcasts to listen to!

The New Yorker and New Republic have also considered the style and clothing of O’Keeffe

Take a look inside O’Keeffe’s home with Incredible Artist Homes: Part II. The Modern Pioneers