Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Margaret Watkins, the Photographer Who Left a Mystery Behind

By Adam Hencz

In the early 1970s Joseph Mulholland received a present in a form of a box from his front door neighbor Margaret Watkins. He did not know yet that its content was going to fundamentally change the course of both of their lives. Watkins handed over the gift under one condition, that Mulholland was not to open the box until after her death. The large box, a mini version of the traditional Saratoga trunk, wrapped in brown paper, sealed with red strings, kept guarding almost 700 rolls of film and many photographs for another decade before Mulholland found it again after a few years of Ms. Watkins’ passing. She left a mystery behind and the young man rose to the challenge to give detail to that mystery.

One of the finest collections of artistic work achieved by the camera in the interwar era came out of that box, an intriguing story of a strong woman, whose photographs constituted a bridge between pictorialism and modernism in photography and who was also one of the earliest art photographers in advertising. Both the discovery of her pictorial sensitivity and inspiring life as a single woman resonates with the work of Vivian Maier. In the past decade, several exhibitions of Margaret Watkins’ works were mounted internationally, and her inspiring oeuvre is now revived due to the efforts of Mr. Mulholland and French curator Anne Morin.

The Life and Hidden Treasure of Margaret Watkins

Born into a wealthy family, Margaret Watkins spent her childhood in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Her father, Frederick W. Watkins was a prominent merchant in the city, owning a large dry goods store, while her mother, Marion Anderson, was a Scottish immigrant, born in Glasgow into a prominent family. Her aunt and her four sisters took turns coming to live in Hamilton with the family, looking after the house, and helping to bring up the Watkins kids, who learned much about arts and crafts from their aunts. By the age of 15, Margaret was selling her own crafts in her father’s department store, just when he filed for bankruptcy. Margaret became the savior of the family by producing works, inventing, and making objects and costumes with her hands.

Pictorialism in the United States

In 1908, Watkins left Ontario and her bourgeois home to join the Roycroft Arts and Crafts Community and the Sidney Lanier Camp, two rural utopian communities where she learned about photography. As an itinerant artist, Watkins never had a place of her own, was taking precarious jobs working hard, but with little or often no pay. She began working closely with photography in 1913 when she moved to Boston and started working as an assistant in a portrait and commercial photography studio. In 1914, she borrowed money to go to Clarence H. White’s summer school, where her interest in working with photography solidified. Her early works reflect the school’s prominent approach to photography as well as the pictorialist influence of photographers and artists like Arthur Wesley Dow and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Portraits

In 1915, Watkins moved to Greenwich Village, New York, and landed a job with photographer Alice Boughton. She began studying under Clarence H. White at his schools in New York and Maine. While an assistant in New York, she developed her own method of portrait photography, taking an approach that references renaissance paintings and psychological portraits with soft focus, delicate lighting, and intimate resemblance to photographs of Nadar from the late 19th century. After completing her formal training she continued to stay at CHW School as a teaching assistant from 1917 until 1920 when she became a full-time educator.

Success in New York

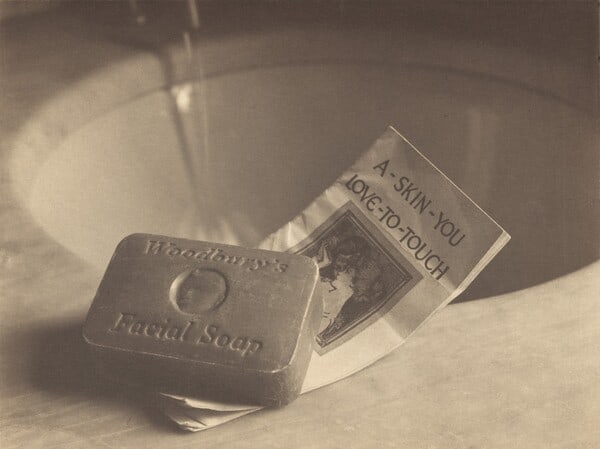

The 1920s was the height of Watkins’ career as an artist and professional photographer. In 1920 she opened a studio and started working as a freelance photographer, working in advertising with clients like the Vanity Fair magazine and The New Yorker, as well as receiving commissions and steady contracts from Macy’s Department Store and the J. Walter Thompson Company. She became a sought-after photographer, who revolutionized advertising photography, creating photographs marked by strict geometric forms, precise design, and composition. Watkins’ particular interest in the home and the inheritance of the home and its objects led to the reformulation of modernist photographic images, ready to be caught by the new advertising at the time. Her images of soaps, pots and pans, knives, and many other everyday objects helped to reframe the image of domestic commodities and led to the artistic documentation of the home as well as raising questions around home labor and women’s domestic and gender roles.

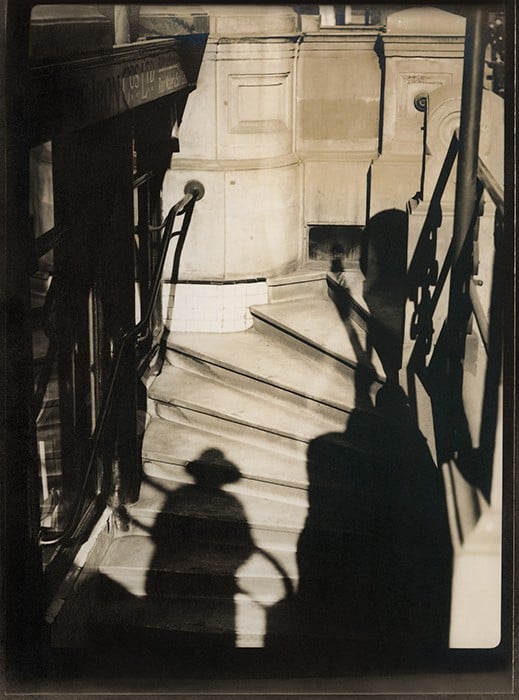

Her fine art photographs, with a clear focus on forms, shadows, and still-life scenes, were exhibited in San Francisco and Japan. Her series titled Domestic Symphonies is considered one of the most celebrated collections of her photographs. With this series of still-life photographs, Watkins received critical acclaim and set new standards of acceptability with the appropriation of everyday objects into the art world.

Street Photography in Europe

In 1928, Watkins left New York for what was planned to be just a six-week trip to Europe but ended up lasting 40 years. She never returned to New York. Watkins arrived in Glasgow at her maternal home, inherited by three elderly aunts. The house was cavernous, with four stories, many fireplaces, and rooms as well as an attic bathroom that served as a darkroom for Watkins who tried to maintain it with photography while taking care of her elderly relatives. In the first years after her arrival in Glasgow, she constantly took short trips around Europe to maintain her connection with the art world such as a trip to Cologne’s Pressa Fair, and to take photographs in Paris, London and Moscow. She embarked on street photography, specializing in storefronts and displays. Through the 1930s, she took many streetscapes in Glasgow and recorded the city as it was back then through impersonal photos of workers and industrial structures.

Photomontages

In the 1930s, Watkins’ funds were running low. She began a series of composite photographs for carpet and textile designs which she intended to sell, but with no success. She constructed commercial designs forming geometric fractals of her photographs, creating abstract iterative photomontages. Her last years in the 1960s were spent indoors, surrounded by a large collection of books and memorabilia. She lived a hand-to-mouth life, selling items and furniture from the accumulations of her family to live.

Legacy and Discovery

A few years before her death in 1969, Watkins left a Saratoga trunk to her good friend and neighbor Joseph Mulholland, leaving a mystery about her life behind – Mulholland did not know about Watkins’ successful artistic career in North America back then. Twenty-eight years since her passing, after Mulholland’s relentless research and efforts to put Watkins’ oeuvre on the map of the art world, the National Gallery of Canada put on an exhibition of her works after years of evaluation and copyright debates. Today, a traveling retrospective exhibition titled Black Light shows 120 of her photographs from early pictorial images through domestic symphonies to abstract works.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more on similar contemporary photographers:

Vivian Maier

Francesca Woodman

Robert Mapplethorpe

Wondering where to start?