Articles & Features

What is Dadaism, Dada Art, or a Dadaist?

Originally a colloquial French term for a hobby horse, Dada, as a word, is nonsense. As a movement, however, Dadaism proved to be one of the revolutionary art movements in the early twentieth century, born as a response to the modern age.

Watch our video overview of the movement and read on to learn more about Dadaism’s key ideas, major dadaist artists, and most famous Dada art.

Know someone who would find this article interesting?

Key dates: 1916-1924

Key regions: Switzerland, Paris, New York

Keywords: Chance, luck, nonsense, anti-art, readymade

Key artists: Hugo Ball, Marcel Duchamp, Hans (Jean) Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hannah Höch, Man Ray, Francois Picabia

Key characteristics: Humoristic, tending towards the absurd, satirical attitude towards authority

Dadaism: Origins and Key Ideas of the Art Movement

During the First World War, countless artists, writers, and intellectuals who opposed the war sought refuge in Switzerland. Zurich, in particular, was a hub for people in exile, and it was here that Hugo Ball and Emmy Hemmings opened the Cabaret Voltaire on February 5, 1916. The Cabaret was a meeting spot for the more radical avant-garde artists. A cross between a nightclub and an arts center, artists could exhibit their work there among cutting-edge poetry, music, and dance. Hans (Jean) Arp, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco and Richard Huelsenbeck were among the original contributors to the Cabaret Voltaire. As the war raged on, their art and performances became increasingly experimental, dissident and anarchic. Together, they protested against the pointlessness and horrors of the war under the battle cry of DADA.

Reacting against the rise of capitalist culture, the war, and the concurrent degradation of art, artists in the early 1910s began to explore new art, or “anti-art”, as described by Marcel Duchamp. They wanted to contemplate the definition of art, and to do so they experimented with the laws of chance and with the found object. Theirs was an art form underpinned by humor and clever turns, but at its very foundation, the Dadaists were asking a very serious question about the role of art in the modern age. This question became even more pertinent as the reach of Dada art spread – by 1915, its ideals had been adopted by artists in New York, Paris, and beyond – and as the world was plunged into the atrocities of World War I.

Advent of the Readymade

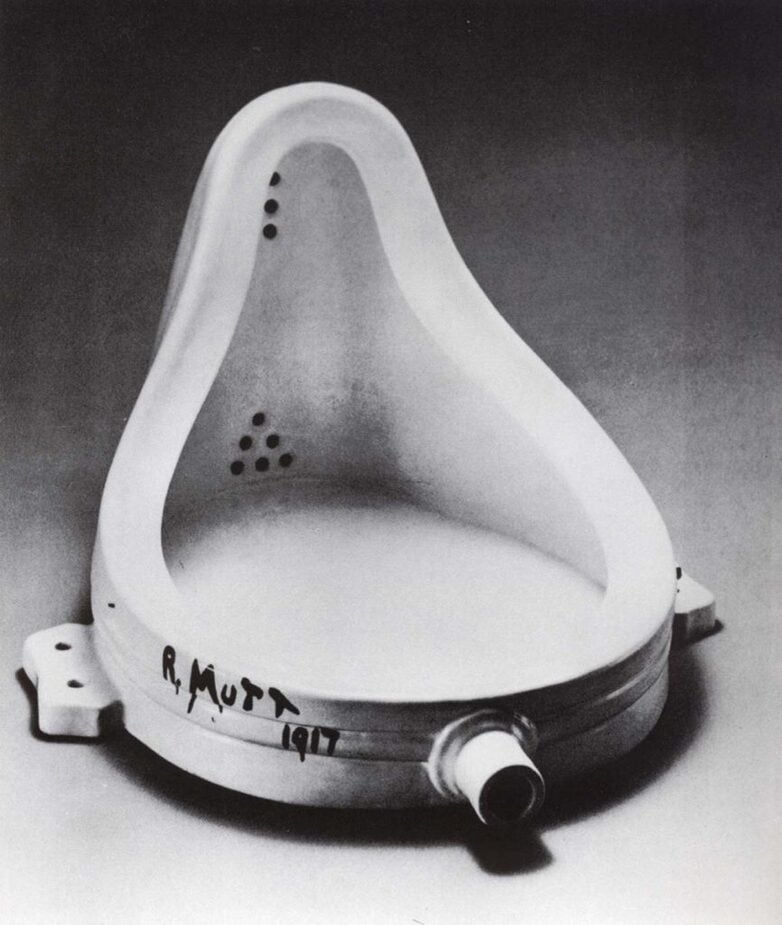

One of the most iconic forms to emerge amidst this flourish of Dadaist expression was the readymade, a sculptural form perfected by Marcel Duchamp. These were works in which Duchamp repurposed found or factory-made objects into installations. In Advance a Broken Arm (1964), for instance, involved the suspension of a snow shovel from a gallery mount; Fountain (1917), arguably Duchamp’s most recognizable readymade, incorporated a mass-produced ceramic urinal. By taking these objects out of their intended functional space and elevating them to the level of “art,” Duchamp poked fun at the art establishment while also asking the viewer to seriously contemplate how we appreciate art.

Different modes of Dadaism

As Duchamp’s readymades exemplify, the Dadaists did not shy away from experimenting with new media. For example, Jean Arp – a sculptor who pioneered dadaism – explored the art of collage and the potential for randomness in its creation. Man Ray also toyed with the arts of photography and airbrushing as practices that distanced the hand of the artist and thus incorporated collaboration with a chance. Beyond these artistic media, the Dadaists also probed the literary and performance arts. Hugo Ball, for instance, the man who penned the unifying manifesto of Dadaism in 1916, investigated the liberation of the written word. Freeing text from the conventional constraints of a published page, Ball played with the power of nonsensical syllables presented as a new form of poetry. These Dadaist poems were often transformed into performances, allowing this network of artists to move easily between media.

Examples of Famous Dada Art

The movement has brought many famous artworks. Here are a selected few examples of dadaism art:

- Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)

- Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913)

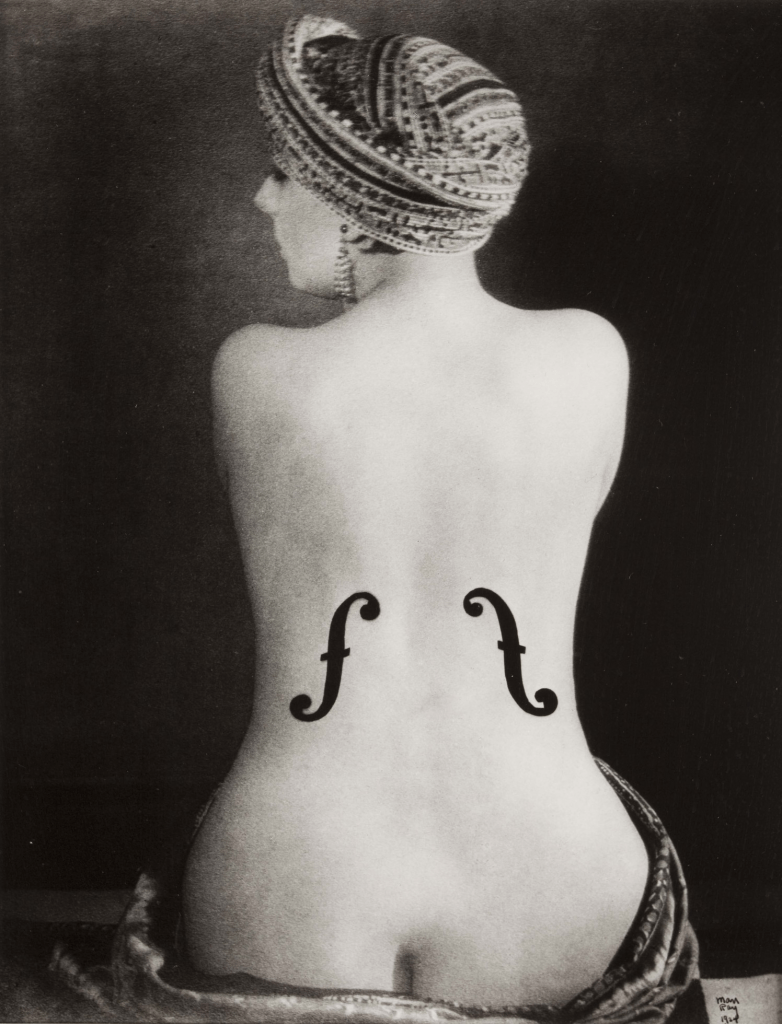

- Man Ray’s Ingres’s Violin (1924)

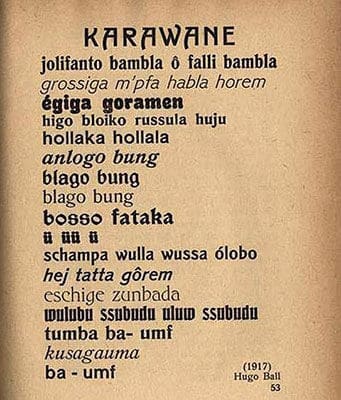

- Hugo Ball’s Sound Poem Karawane (1916)

- Raoul Hausmann’s Mechanical Head (The Spirit of our Time) (1920)

- Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919)

1. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal to the Society of Independent Artists. The Society refused Fountain because they believed it could not be considered a work of art. Duchamp’s Fountain raised countless important questions about what makes art art and is considered a major landmark in 20th-century art.

2. Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913)

“In 1913, I had the happy idea to fasten a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and watch it turn,” said Marcel Duchamp about his famous work Bicycle Wheel. Bicycle Wheel is the first of Duchamp’s readymade objects. Readymades were individual objects that Duchamp repositioned or signed and called art. He called Bicycle Wheel an “assisted readymade,” made by combining more than one utilitarian item to form a work of art.

3. Man Ray’s Ingres’s Violin (1924)

By painting f-holes of a stringed instrument onto the photographic print of his nude model Kiki de Montparnasse and rephotographing the print, Man Ray altered what was originally a classical nude. The female body was now transformed into a musical instrument. He also added the title Le Violin d’Ingres, a French idiom that means “hobby.”

4. Hugo Ball’s Sound Poem Karawane (1916)

Founder of the Cabaret Voltaire and writer of the first Dadaist Manifesto in 1916, most of Ball’s work was in the genre of sound poetry. In 1916, the same year in which the published the first Dadaist Manifesto, Ball performed the sound poem Karawane. The opening lines were:

jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

Hugo Ball

großiga m’pfa habla horem

The rest of the poem continued along the same lines. Though the poem could be confused with random, mad ramblings, sound-poetry was really a deeply considered method in experimental literature. The idea was to bring the sounds of human vocalization to the foreground by removing everything else.

5. Raoul Hausmann’s Mechanical Head (The Spirit of our Time) (1920)

Raoul Hausmann was a poet, collagist, and performance artist, who is best known for his sculpture entitled Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time). The manikin head made from a solid wooden block is a reversal of Hegel’s assertion that “everything is mind.” For Hausmann, man is empty-headed “with no more capabilities than that which chance has glued to the outside of his skull.” By raising these topics, Hausmann wanted to compose an image that would shatter the mainstream Western conventions that the head is the seat of reason.

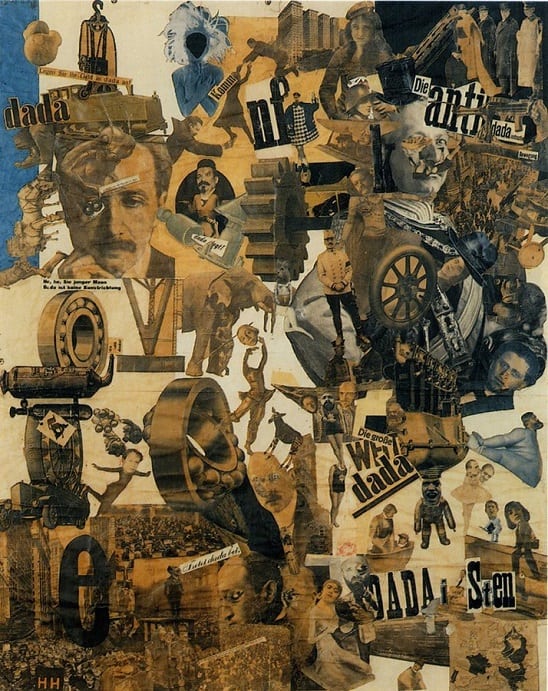

6. Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919)

Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany is a collection of Dada and “anti-dada” elements. The piece, which is made up of cuttings from newspapers and magazines, is flooded with topical images that have been merged together to show Höch’s view on Germany, dadaism, and the role of women in both contexts. Many male Dadaists had great ideas about gender equity and how to go about it but there was a dissonance between the theories and their actions. Out of frustration, Hannah Höch used her work to showcase her thoughts on the matter.

Reception, Downfall, and Dissemination of Dadaist Ideals

The bold new approaches of the Dadaists stirred controversy within contemporary culture. Their swift break from tradition, their impassioned pursuit of a new mode of expression, and their willingness to bring the revered world of “fine art” back to a more level and egalitarian playing field through both humor and inquisitive investigation allowed Dada artists to attract both fans and foes of their work. Some saw Dadaist expression as the next step forward in the avant-garde march; others missed the significance and instead saw works, such as Duchamp’s readymades, as not art but simply their constituent objects (leading to some of the originals being relegated to the refuse pile).

Dadaism gripped audiences into the 1920s, but the movement as a whole was destined to crumble. Some, like Man Ray, found their inclinations moving into the subconscious realm of Surrealism; others found the pressures on the modern European artist too weighty to bear. The rise to power of Adolf Hitler in the 1930s dealt a powerful blow to the modern art world, as the maniacal despot sought to root out the sprouts of modern art, a field he considered “degenerate.” As a result, Dada artists witnessed their works mocked or destroyed and thus chose to escape the stifling air of Europe for the more liberated artistic climate of the United States and beyond.

Though many of these initial members scattered, the ideals of Dadaism remained alive and well among contemporary artists. In many regards, one can see the threads of Dada revived. For example, during the Pop Art era, Neo-Dadaism presented motifs and cultural commentaries interpreted with a hint of Dadaist intrigue. But it was in the latter half of the twentieth century that the full impact of the Dadaist moment was realized. In addition to the two major international retrospectives dissecting the Dadaist oeuvre (one in 1967 in Paris and another in 2006 at various international venues), greater research was lavished on the comprehension and preservation of their legacy.

Collecting Dada Art

Though offering a universal appeal, Dadaist works can prove a challenge to collect. Beyond issues of authenticity, it is difficult to chart or project the prices such works will achieve, a problem owed to the sheer variety of media. That being said, one can note the consistency with which Dadaist works have exceeded expectations at auction. The notable sale of Marcel Duchamp’s Nu sur nu (1910-1911) for more than $1.4 million in June 2016 doubled the estimated sales price of between $555,000 – $775,000. François Picabia’s Ventilateur (1928) sold at Sotheby’s in February 2016 for more than $3.1 million at the higher end of its predicted sales range. What this trend seems to suggest is that the interest in Dada art expression and the Dada movement is still alive and well, with collectors knowledgeable with regards to the good deals that might pop up at auction.

Frequently asked questions about Dadaism

What is Dadaism?

Dadaism is an artistic movement from the early 20th century, predating surrealism and with its roots in a number of major European artistic capitals. Developed in response to the horrors of WW1 the dada movement rejected reason, rationality, and order of the emerging capitalist society, instead favoring chaos, nonsense, and anti-bourgeois sentiment.

Who are the main Dadaist artists?

The most renowned Dada artists are Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray in Paris, George Grosz, Otto Dix, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, Max Ernst, and Kurt Schwitters in Germany, and Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco and Jean Arp in Zurich.

Where did Dadaism originate?

There is some disagreement as to where Dada was founded. Many believe that the movement first developed in the Cabaret Voltaire, an avant-garde nightclub in Zurich, others claim a Romanian origin. What is clear is that there was a pan European sensibility emerging during WW1, especially during 1916, and that clear adherents the main themes can be identified in Zurich, Berlin, Paris, Hanover, Cologne, the Netherlands and even as far away as New York.

What are the main characteristics of dadaism?

A Dadaism is often characterized by humor and whimsy, tending towards the absurd. This kind attitude was used as a satirical critique of the prevailing societal and political systems, to which the onslaught of WWI was largely attributed to.

What does dadaism mean?

The name Dada is one derived from nonsense and irrationality. In some languages, it meant ‘yes, yes’ as a parody of the population’s senseless obedience to authority, whilst in others, it had completely different meanings and connotations. The name is attributed to Richard Huelsenbeck and Hugo Ball, although Tristan Tzara also claimed authorship – the idea being that it would have multiple nonsense meanings.

How is dadaism a reaction to WW1?

Dadaism was a movement with explicitly political overtones – a reaction to the senseless slaughter of the trenches of WWI. It essentially declared war against war, countering the absurdity of the establishment’s descent into chaos with its own kind of nonsense.

Which composer was most closely associated with dadaism?

Dada ideal also extended to the field of sound. Among others, Francis Picabia and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes realized Dada music to be performed at the 1920 Festival Dada, but also renowned composer Erik Satie also dipped into Dadaist sound experiments.

Relevant source to learn more

Read more about Art Movements and Styles Throughout History.