Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Sophie Taeuber-Arp

By Adam Hencz

“In a flower, in a beetle, every line, every form, every color has arisen from a deep necessity.”

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

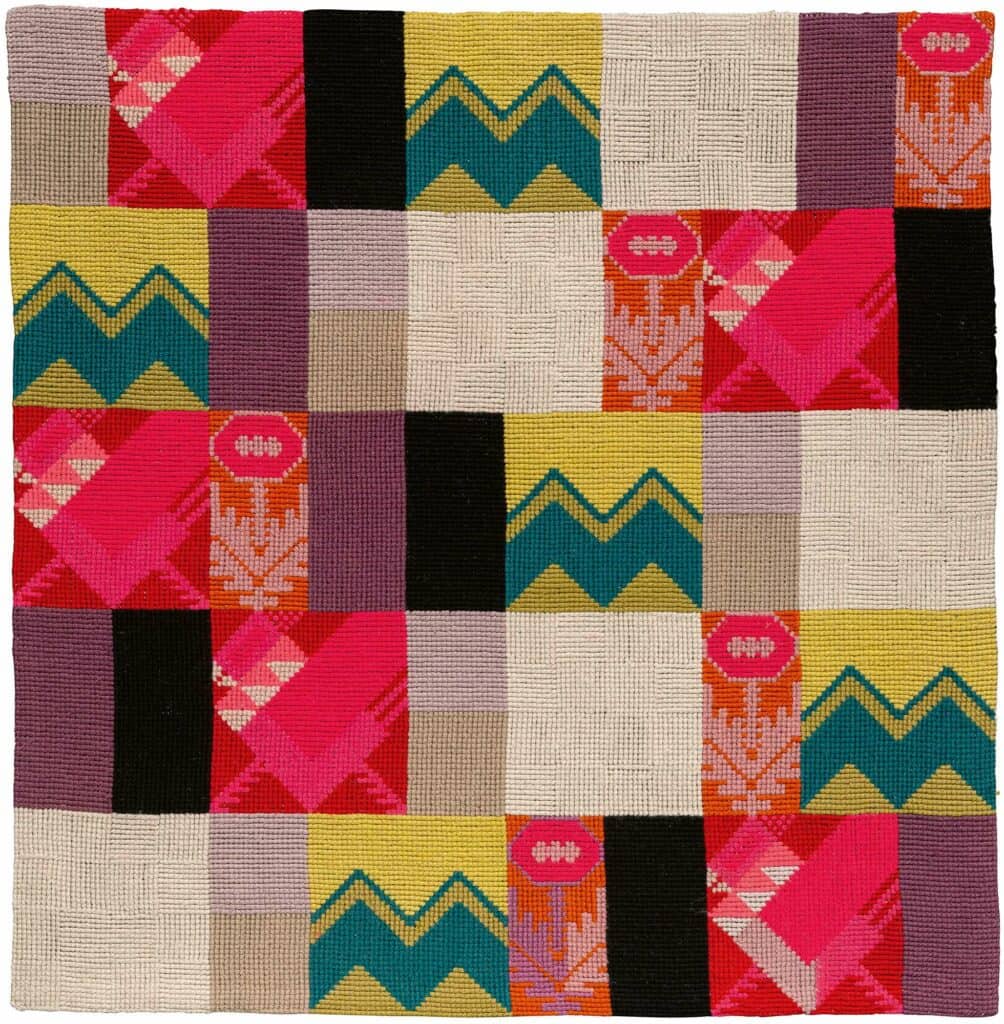

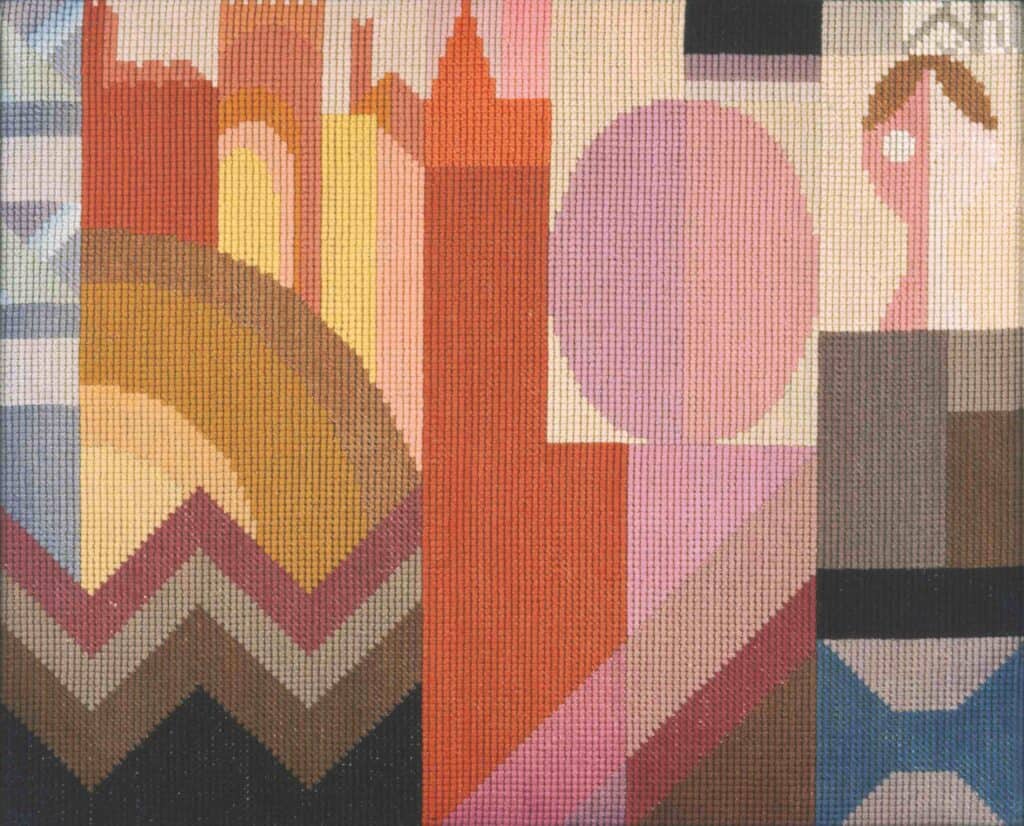

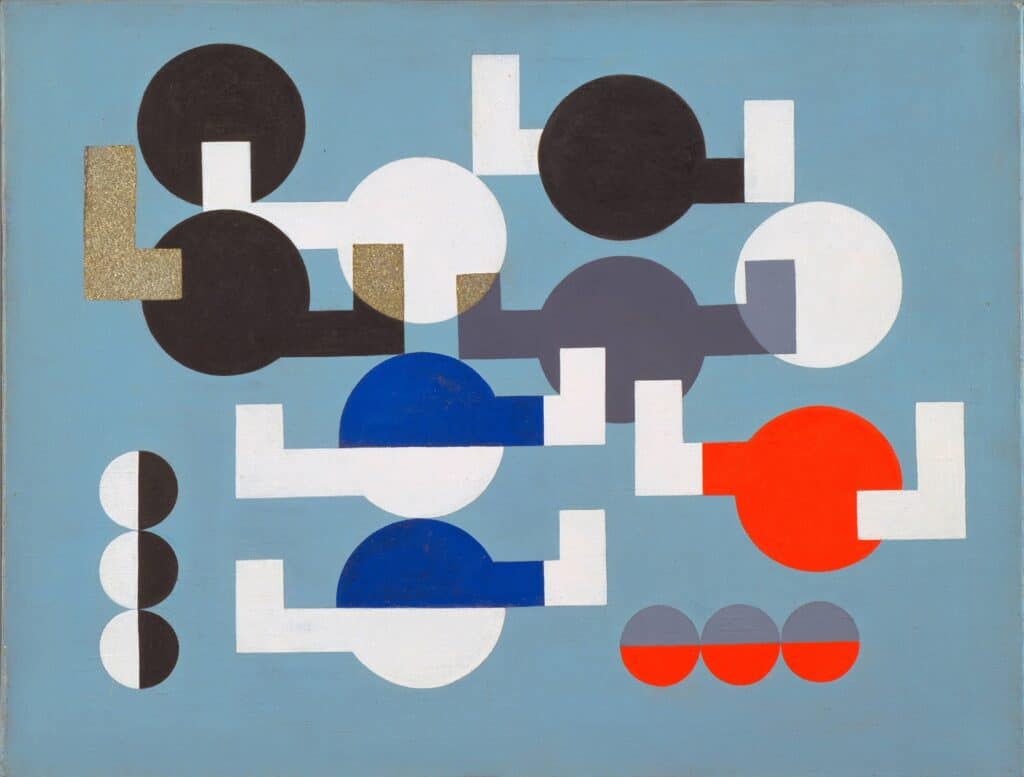

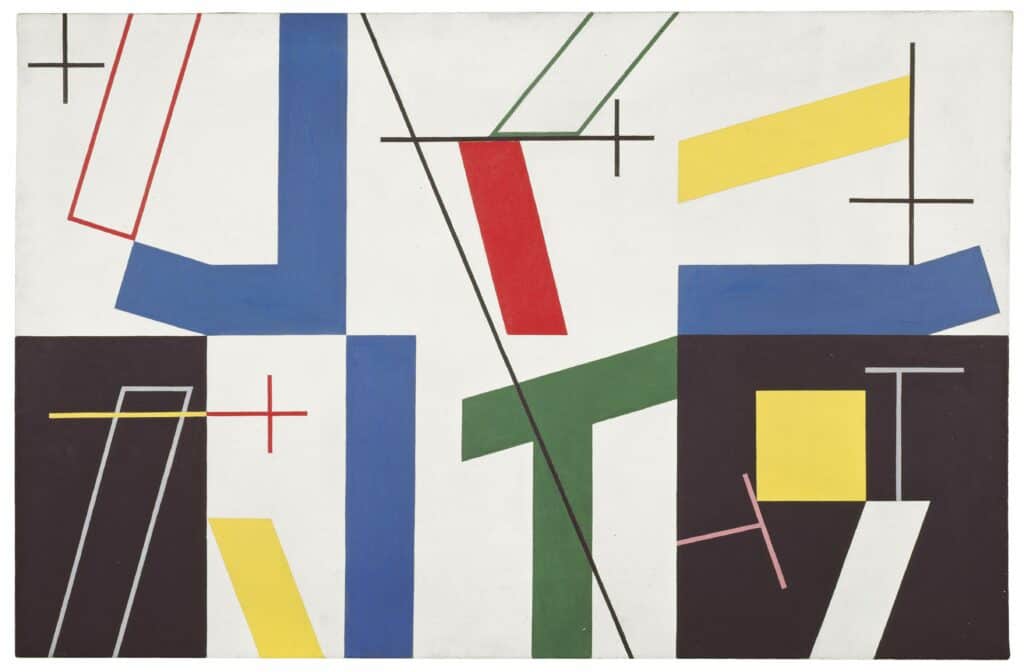

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series features artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art history books or largely invisible for most of their careers. A leading pioneer of 20th abstraction, Swiss painter, sculptress, dancer and textile artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp has long been eclipsed by other forefront artists of the century and has been unduly left outside the fine art canon. Her work uniquely combined an exploratory approach to shapes and crafted materials, works on paper, paintings, relief sculptures and an interest in dance and movement, with a love of geometric abstraction developed as a result of her work in embroidery and tapestry. At long last, a major retrospective in joint curation by Tate Modern, MoMa and Kunstmuseum Basel now celebrates her pioneering figure that forged a new path for the development of abstraction.

Studying arts and crafts

Sophie Taeuber was born in Davos and grew up in Trogen, Switzerland. After she lost her father at the age of two, her mother had to provide for the family, holding various jobs besides running a boarding house. She taught her young daughters various crafts, nurtured the children’s creativity and led a family where art and culture were part of daily life. At the age of 18, enchanted by textile design, embroidery and lacework, Sophie Taeuber enrolled at the School of Applied Arts in St. Gallen, a town that had been the centre of the textile and embroidery industries for centuries.

In the autumn of 1910, Taeuber-Arp left for Munich to attend the workshops of Wilhelm von Debschitz at his reform-oriented school, where men and women studied and attended life drawing classes together, and where the distinctions between the fine and the applied arts were dissolved under the rubric of design (Gestaltung). The training she received was heavily influenced by the English Arts-and-Crafts movement as she learnt in an environment in which fine workmanship governed. Behind the walls of these experimental studios, she learned a variety of techniques and disciplines, including woodworking and architecture. In the following years, she split her time between Munich and Hamburg, where she studied weaving at the Decorative Arts School.

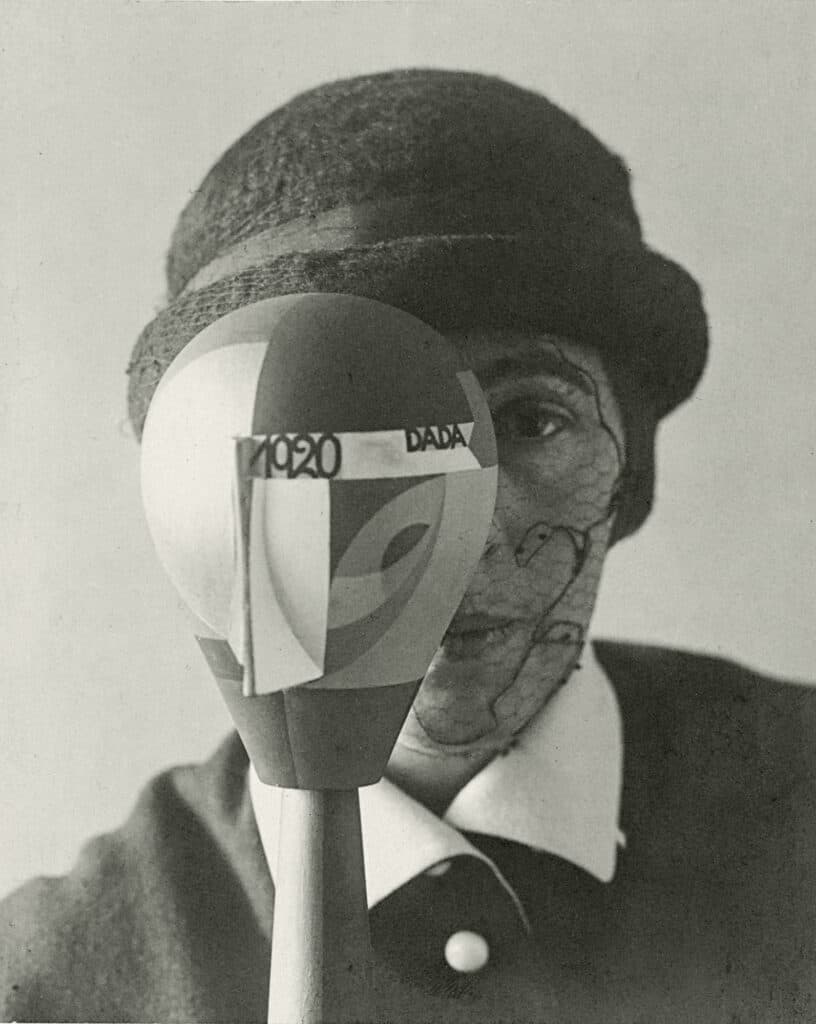

Marionettes and Dada

Once the First World War broke out in 1914, Taeuber-Arp settled in Zurich, which during the war became a refuge and international hub for the avant-garde. It was in Zurich that she met her lifelong partner, artist and poet Jean (Hans) Arp for the first time in November 1915 during the exhibition Modern tapestries, embroidery, paintings and drawings at Galerie Tanner. They soon collaborated on mutual works of art and began a creative relationship that would last for almost three decades. In Zurich Taeuber-Arp also took modern expressive dance classes at Rudolf von Laban’s influential School of Art Movement and frequently performed at the most happening place in town, the Cabaret Voltaire. Together with her future husband, she was an active member of the anti-bourgeois Dada movement by taking part in a large number of exhibitions of artistic works as well as performing on the occasion of the opening of the Galerie Dada in 1917. For the next twelve years, she taught in the arts and crafts division of Zurich’s Trade School, a job that provided her with a dependable livelihood.

Thanks to her training in applied arts, Taeuber-Arp was a skilled woodworker, a skill that she nurtured while creating a series of portrait-like wooden sculptures as well as designing the avant-garde stage set and an entire ensemble of marionettes for a new satirical version of Carlo Gozzi’s play König Hirsch (Il ré cervo) at the Swiss Marionette Theater in Zurich. These geometric-turned-wood shapes of puppets with movable limbs purely reflected Taeuber-Arp’s sensitivity for space and rhythm and her ability to combine her experience from performing arts with her craft.

Travels and interiors

In the 1920s, Arp and Taeuber travelled widely and cultivated their artistic contacts from Zurich to spend time in Paris and Ascona, and to see Rome, Naples and Pompeii. In 1922 the couple married in Pura in Ticino. They continued working on tapestries and handicrafts, but her teaching post took most of her time and energy. After being on the move, the couple relocated to Strasbourg in 1926, where Taeuber-Arp shortly built a successful career as an interior designer. She designed avant-garde architectural interiors, stained-glass windows, monumental wall murals and interior designs for private houses like André Horn’s apartment as well as for Hotel Hannong and the grandiose amusement centre Aubette. During the execution of these works, Taeuber-Arp continued to commute between Strasbourg and Zurich.

Painting and the exploration of the line

At the turn of the decade, she resigned from her teaching post in Zurich and bought a piece of land in Clamart outside Paris, where she built a home-studio based on architectural plans and interior design made by Taeuber-Arp herself. During this period, she created some of her most recognisable and strongest works in geometric paintings and abstract painted reliefs, which today are broadly classified as Constructivist. Paris also allowed her to build strong relationships with Surrealist artists, as the city became Europe’s most fashionable art hub for artists exploring non-figurative art including Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marcel Duchamp. On the rise of Surrealism Taeuber-Arp was actively involved in the movement’s main artists groups Cercle et Carré and its successor organisation Abstraction-Création. The year 1937 marked the single most important presentation of her art in her lifetime at Kunsthalle Basel, where twenty-four of her works were exhibited in the group exhibition Konstruktivisten. Even though her words were overshadowed by that of her spouse, Hans Arp, her works were sought by both museums and collectors. She exhibited in the museum in Lodz and her works were included in the museum collection as well. The collector Marguerite Hagenbach also purchased works by Taeuber-Arp on a regular basis.

The Second World War forced the couple to flee to southern France in 1940 and then later crossing over to Zurich in 1942. As the war was raging, her works became concentrated on the medium of drawing and exploration of the line. Even though drawing has always been part of her practice, it became her medium of choice primarily due to the general scarcity of art supplies. These drawings remain the last works in her multifaceted oeuvre before her tragic death. On 13 January 1943, while staying at artist Max Bill’s house, she failed to notice that the wood-burning stove’s flue was blocked, and suffered carbon monoxide poisoning in her sleep. Devastated by her death, Hans Arp retreated to a monastery, eventually beginning to create again by writing a series of poems to his deceased wife.

Rediscovery

In early 2021, the Kunstmuseum Basel dedicated a comprehensive travelling retrospective Living Abstraction to Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s oeuvre. The show is now on display at the Tate Modern between 15 July and 17 October, and will finally move to the Museum of Modern Art in November, where it will be the first major US exhibition in 40 years to explore the artist’s innovative and wide-ranging body of work.

Relevant sources to learn more

Ongoing exhibition at Tate Modern

Previous editions of the Lost (and Found) Artist Series:

Katarzyna Kobro

María Izquierdo

Seydou Keïta

Martín Ramírez

Judy Rifka

Tehching Hsieh

Sonia Gomes

Huguette Caland

Ron Gorchov

Samia Halaby

Rose Hilton

Amaranth Ehrenhalt

Bill Traylor

Hannah Ryggen

Samia Halaby

Huguette Caland

Agnes Pelton

Wondering where to start?