Articles and Features

Agents Of Change: Plastic. Or How Plastic Became An Era-Defining Material

“Materials in sculpture play one of the fundamental roles. The genesis of a sculpture is determined by its materials. Materials establish the emotional foundations of a sculpture, give it a basic accent and determine the limits of its aesthetical action”.

Naum Gabo

In a world that depends on plastics whilst simultaneously and tragically drowning in it, it sounds incredible that barely a hundred years ago plastic was the most innovative of materials.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the world of synthetic chemistry began to boom, in particular to replace expensive natural materials like horn, amber, shellac, and tortoiseshell, to later become – in the aftermath of World War II – an integral part of everyday life as well as the iconic material of the century.

Low-cost and versatile, plastics have immediately drawn the attention of artists with a penchant for the exploration of new materials and techniques to develop revolutionary means of expression. They are light, easy to cut and to shape in the most versatile ways, rigid or flexible, transparent or opaque, coloured or not; for this reason they have been extremely intriguing for sculptors whom they allow to enhance the effects of light and space. There is no synthetic compound that has not been used as a contemporary art material, whether as a support, a medium, or a component of the work.

Even though we will focus on the use of solid plastic and its three-dimensional features, we shall not forget that an even greater impact in the art world was the introduction of synthetic materials in the form of acrylic paints, an indispensable element in the development of entire artistic movements.

Plastic Pioneers

The entry of plastic materials into the art world took place in the same years in which the avant-garde movements developed, but it is mainly due to the experimentation carried out into the formalist potential of the material by rationalist artists, initially part of the constructivist movement, then participating actors of Bauhaus.

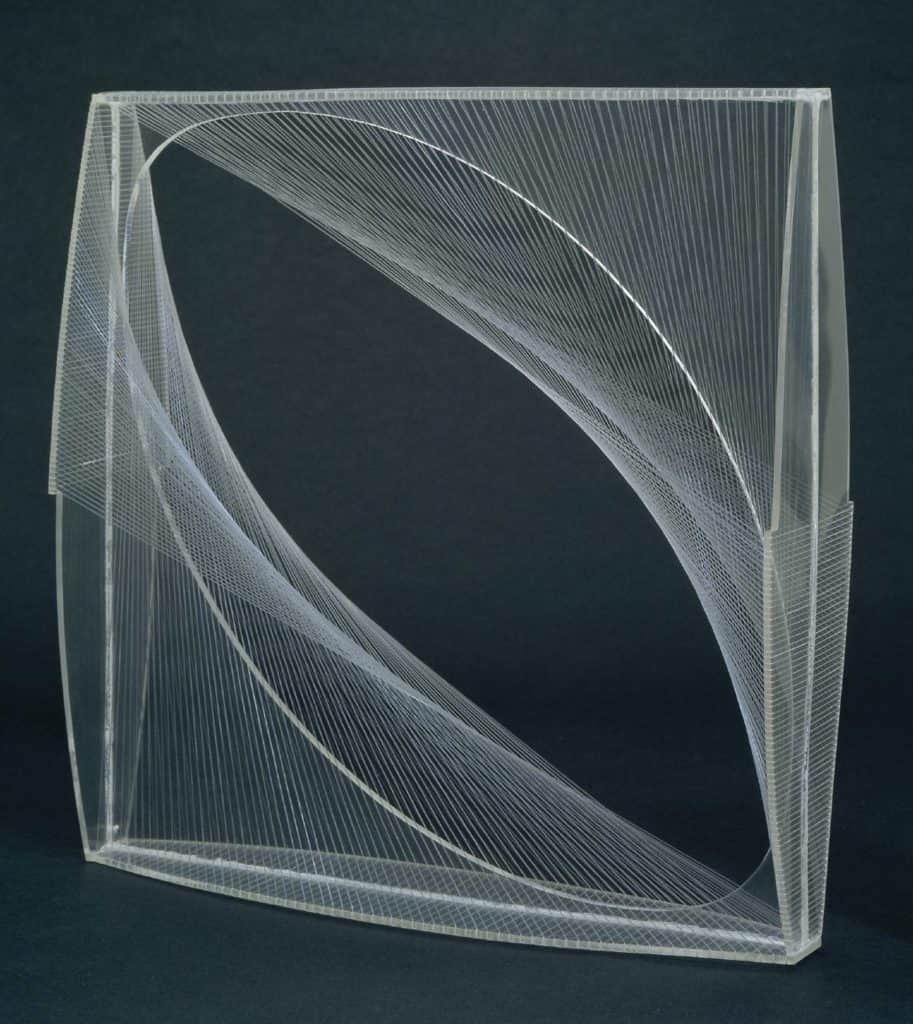

First and foremost, the Russian Naum Gabo sailed the uncharted waters of synthetic materials with the experimental use of Celluloid, the commercial name for cellulose nitrate: an innovative product made from chemically treated cotton that could be easily moulded into a myriad of shapes. Inspired by its lightness and transparency, as well as ease of processing, Naum Gabo began to use Celluloid for the construction of his three-dimensional artworks, trying to explore all the possible optical effects, brightness, transparency, and permeation the new material offered. Though the first documented works date back to 1916, the artist had already created sculptures with parts in this new and extraordinary material during the previous years.

Unfortunately, celluloid – especially in the early days of its production – proved to be an unstable product, and most of Gabo’s early work has gone completely lost due to deterioration. When, a few years later, cellulose acetate was introduced to the market, Gabo immediately seized the opportunity and used this new, more stable material for his Constructions in Space, transitioning away from celluloid completely.

For Gabo, the sculptural idea itself was meaningful, more than its materiality or even the notion of being hand made by the hand of the artist: he did not place much stock in the concept of something being ‘original’. In fact, most of the works by Gabo we can admire today in museums have been reconstructed from scratch or rebuilt by the artist himself. He made twenty-six versions of Linear Construction in Space No. 2 and seventeen versions of Linear Construction in Space No. 1.

Throughout his life-long activity, Naum Gabo experimented with inexhaustible enthusiasm and creativity with the new plastic materials gradually made available by technology, always accompanied by his brother Antoine Pevsner, a proponent of constructivist principles and an internationally renowned artist himself.

In the mid-1930s, Gabo began to use what was commercially known as Perspex or Plexiglas, which he managed to obtain even before it was available on the market thanks to his acquaintance with the director of the British industry that had invented it.

Finally, in 1942, he discovered the potential of Nylon, a recently developed synthetic material in the form of fibres and filaments, which he used systematically in his body of work from that point on. Gabo fully transformed the artist into a modern technician who uses rule and compass, and accurately follows the principles of technology. He wrote: “we construct our work as the universe constructs its own, as the engineer constructs his bridges, as the mathematician his formula of the orbits”.

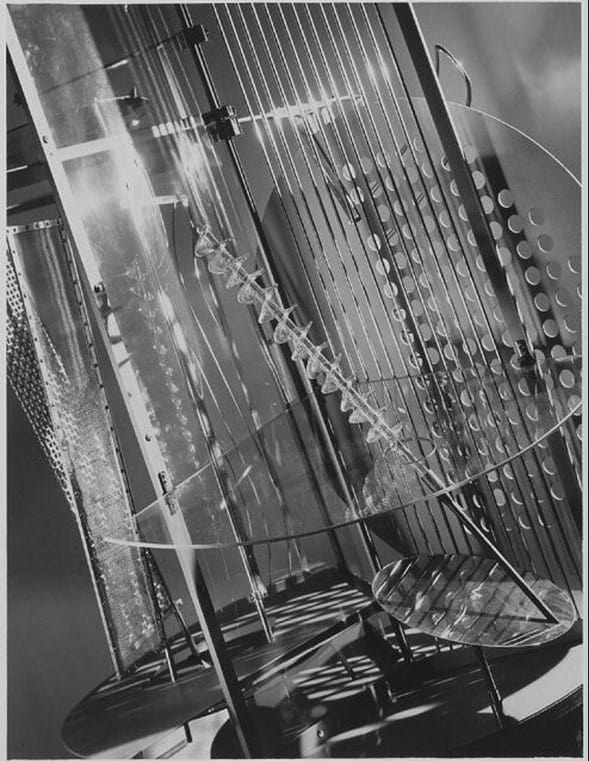

Plastics also proved to be perfectly functional for the work of László Moholy-Nagy who was extremely interested in demonstrating the relationship between art, science, and industry. Plastics’ flexibility and workability to obtain concave and convex shapes led him to use Celluloid, cellulose acetates, then Bakelite, Galalith, and finally Plexiglass for the realisation of three-dimensional pieces composed of plastic sheets, moulded, perforated, and eventually lit by lights hidden within. But Moholy-Nagy’s most ambitious achievement was perhaps Light Space Modulator: a machine driven by an electric motor creating unexpected visual effects thanks to the interplay of light, volumes, and transparency.

It is not surprising that artists open to innovation exploited the new synthetic polymer compounds since their first appearance and availability: expensive and laborious traditional techniques could easily be avoided and, at the same time, represent new perceptions of space and time through forms and volumes made up not only of material but also void and light.

With the Second World War, the pioneering phase of the use of synthetic materials came to an end and plastic slowly became part of the everyday.

From the 1950s to the present

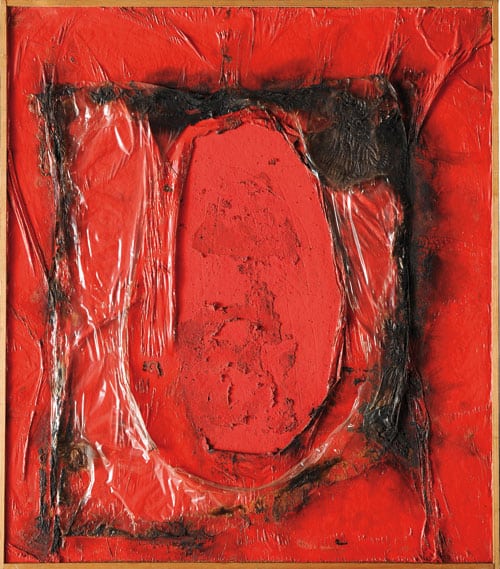

Among the first relevant experiences in the aftermath of the war, the Italian artist Alberto Burri found in the materiality of burnt plastic the way to express the trauma of violence suffered both personally and collectively. Under his hands, plastic lost its reassuring industrial smoothness and was instead used to represent the disturbing beauty of a troubled living organism, accompanied by the scarred surface of destruction and decay.

From the 1960s, the use of plastic in sculptures and installations has become increasingly common: artists of all genres have explored the expressive potential of plastic in all its forms, from acrylic and epoxy resins to polyurethane, and polyester. PVC, a 1960s entry in the world of plastic products, immediately drew the attention of Christo and Jeanne-Claude and turned out to be the perfect fit for their Packages.

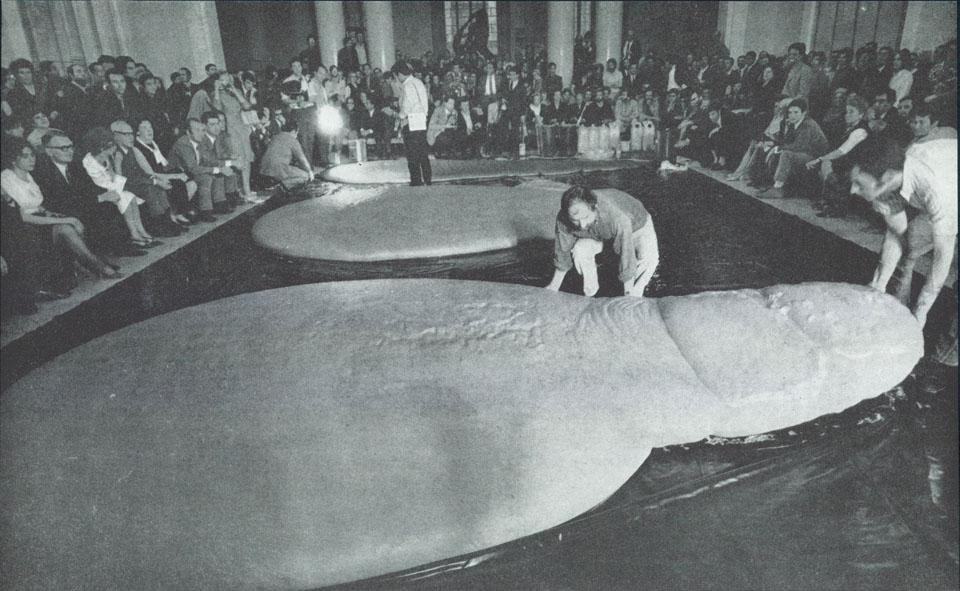

It is astonishing how every artist seems to have found the synthetic product that better conveyed the essence of his or her aesthetic and artistic research. For the work of French artist César, the best kind of plastic proved to be polyurethane foam, a kind of spume that crystallizes in contact with the air and increases its volume considerably.

The freedom associated with the immense expressive possibilities of this synthetic material became the subject of happenings that made César known all over the world: his public Expansions brought him from Paris to Lund, then Munich, Montevideo, and Rio de Janeiro, London, and Rome. He stated: “When you see my work, you realize that it is purely physical, instinctive, but there is also a man behind it, with a brain. (…) It is touch that puts all the sculptor’s mechanics in motion: is the material that guides imagination”.

The same polyurethane foam – although in a slightly different form – has also been essential for Piero Gilardi and his faithful, though soft, reproduction of natural scenarios. While Carlo Rama used the rubber of bicycle tyres as a medium.

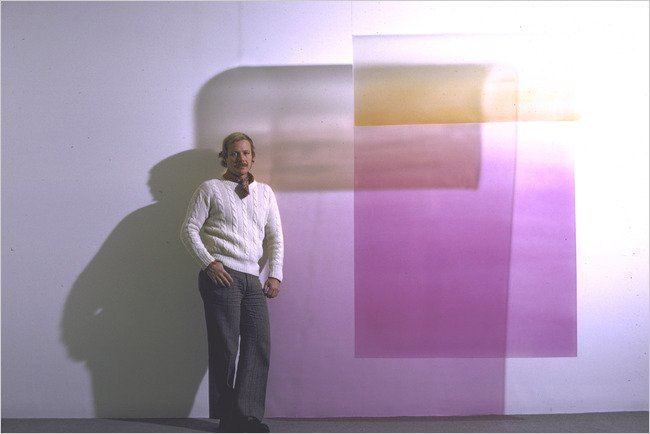

In those same years, across the Atlantic Ocean, an eclectic group of artists began incorporating into their work the latest technologies of the Southern California-based engineering and aerospace industries to create sensuous, light-filled objects revealing the light, space, and energy of postwar Southern California. This loosely affiliated movement under the name of Light and Space, but also sometimes dubbed California Minimalism or even Finish Fetish Art, made the spectator’s experience of perceptual phenomena – light, volume, and scale – the focus of its work. As counterpoints to the abstract expressionists who ruled New York, these artists reinterpreted Minimalism and Op Art aesthetic ideals, but awash with a glossy Southern California vibe.

Among the group, Craig Kauffman conducted audacious experiments in moulding industrial plastic to create ethereal wall-mounted sculptures inspired by the plastic packaging increasingly used to wrap merchandise, as well as reliefs of vacuum-formed plastic in luxuriant colours.

While Mary Corse gained early recognition for a series of white monochromes structures of neon tubing encased in narrow Plexiglas boxes before moving to her best known radiant surfaces with glass microspheres embedded in acrylic paint.

Peter Alexander chose resin as his signature medium, a well-known material to the artist since his experience as a surfer: “When I started working in resin, it was plastic. Art was not made out of plastic in those days. Art was made out of all the things that history has said art is made of. So one of the reasons why I liked plastic was that it was sort of anti-art”. Before shifting to painting and drawing because of the toxicity of his initial medium, Alexander created translucent volumes with slick surfaces, cubes, and wedges whose colour appears to fade depending on where the viewer stands in the same manner the ocean appears to when it meets the continent.

Those same polyester resins that constituted Alexander’s immaculate minimalist volumes attracted as well the attention of artists belonging to another entirely new genre, Hyperrealism. Along with fibreglass, synthetic resin is in fact the main component of the dramatically and compelling banality of Duane Hanson’s sculpted figures and the nudes by John De Andrea, until the more recent gigantic, distorted figures by Ron Mueck and the obsessive details of Marc Sijan’s work.

A completely new innovation in the use of plastic was made by Tony Cragg in his 1981 Britain seen from the North: a bright, seven-meters-long mosaic map of the mainland put together from scavenged plastic objects, some broken, some intact; to the left, a figure representing Cragg himself – who lives in Germany – observing his native land as if through the eyes of an outsider. The artist, who had visited Britain and felt the country’s social and economic difficulties, no longer considered plastic as an innovative primary material, but as waste, symbolic of a society in crisis.

Rachel Whiteread’s approach in her celebrated work EMBANKMENT, commissioned for the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in London, is partially reminiscent of minimalist spatiality but with an intimate intensity. This work of monumental scale is consistent with the artist’s representation of familiar domestic objects in a provoking and unexpected form. Inspired by an old, worn cardboard box found in her mother’s house, piles of 14,000 semi-transparent white polyethylene boxes stacked one on top of the other forming regular or disordered volumes, some towering as high as twelve metres, created an overwhelming labyrinth for the visitors to pass through.

In conclusion, one of the latest tendencies is the self-referential use of plastic to put the spotlight on ecology-related themes, such as environmental pollution and climate change.

In 2017, in front of London’s National Theatre, the sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor unveiled in collaboration with Greenpeace the public art installation Plasticide, depicting a family picnic on a beach plagued by plastic pollution. Part of the artwork was constructed with microplastics collected along the shores of Lanzarote, Canary Islands, to urge consumers, policymakers and packaging producers to cut back on the use of plastics; while the French photographer Alain Delorme meticulously arranged calligraphic shapes made up of thousands of plastic bags to digitally reproduce the poetic natural phenomenon of murmuration, which consists in flocks twisting, weaving, and undulating in the creation of a fluctuating mesh.

A Note on Conservation

Paradoxically, plastic, which is generally identified as the material with the highest risk of environmental pollution because it remains indefinitely as solid waste, in the the art world is sometimes considered non-permanent and inadequate for artistic use because it gets easily altered. The fact is that these materials have been designed for uses other than art, but the durability necessary for an artwork far exceeds those of objects with single-use domestic purposes. As time passes, plastics yellow, fade or darken, but also crack, distort, and crumble apart, deteriorating in an ever-changing and unpredictable way. Moreover, the same type of material produced at different times may show different stability to ageing since the improvement of production technologies provided the market with progressively better quality products, therefore a different origin in terms of production or age can cause very different behaviours.

Consequently, contemporary art requires an extremely high level of technical knowledge, and artists must be aware of the risks they face when using certain techniques or materials both in terms of the duration of their work and their health.

César manipulated large quantities of dangerous substances for several years until he had to stop because of the damage they were causing; while for Duane Hanson, the realisation of his sculptures in fibreglass without taking the necessary precautions led to the disease that was fatal to him.

After all, the history of synthetic materials is so recent that it is difficult to predict what the future will bring; if today’s conservators soak up previous generations’ knowledge of textiles, bronzes, paper, marble, and oil paints on canvas, preserving plastic is a completely new and different challenge, and a conscious approach is the only way to preserve the art of our century for future generations.

Relevant sources to learn more

Degradation of Naum Gabo’s Plastic Sculpture: The Catalyst for the Workshop

These Cultural Treasures Are Made of Plastic. Now They’re Falling Apart