Articles and Features

Alberto Giacometti – Art As a Means of Seeing

By Shira Wolfe

“I do not work to create beautiful paintings or sculpture. Art is only a means of seeing. No matter what I look at, it all surprises and eludes me, and I am not too sure of what I see.”

Alberto Giacometti

Who was Alberto Giacometti?

Boundary-breaking sculptors are those who in their own way pushed the medium of sculpture forwards into new, unique territories. This edition is dedicated to Alberto Giacometti, one of the most influential sculptors in contemporary art. Although he has been linked to the early-20th-century Avant-garde, he developed an unmistakably idiosyncratic style, unique unto itself. Friend of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett and Picasso, he was a tormented genius who explored the human condition and the horrors of his time through the production of his elongated solitary figures, emblems of distress and resilience.

Biography of Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti is Born into Art

Born in a remote Swiss valley in 1901, Alberto Giacometti grew up with art. His father was a successful realist painter, and Giacometti made his first sculpture of his brother Diego at the age of 14. He moved to Paris in 1922, taking his brother with him and continuing to use him as a model. He studied at the Académie de la Grande-Chaumiere where he was taught by the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle. In 1926, he started taking an interest in African art and began moving away from naturalist and academic representation, moving instead towards totemic and wild visions of the figure. The two works that really brought Giacometti to people’s attention were Spoon Woman (1927) and The Couple (1926), which he exhibited in 1927 at the Salon des Tuileries.

Discovering Surrealism

In Paris, Giacometti also discovered Surrealism. He became friends with André Breton and joined the Surrealist movement in 1931. Inspired by Surrealism, Giacometti stopped modelling from life and focused on dreamlike visions. He claimed that he only realised sculptures that presented themselves to him in a finished state, which fit perfectly with the tenets of Surrealism. However, in 1934, Giacometti was working on the powerful piece Hands Holding the Void (Imaginary Object) – his attempt to depict a complete human being of 1.5 metres high – and found himself facing a creative impasse. The piece was a turning point for Giacometti. Not satisfied with the legs, torso and breasts, the artist decided he needed to try working from nature, hiring a model – and, in doing so, he disappointed Breton, who was absolutely against this approach to creating art.

Giacometti became obsessed with attempting to render the head, which he deemed an object unknown and without dimensions, but this interest was met with contempt from Breton, who said: “Everybody knows what a head looks like!” When Giacometti accepted a commission in 1934, this was the final straw for the Surrealists, who felt he was tying himself to the bourgeoisie and expelled him from the group.

Although expelled from the movement in 1935, Surrealism continued to inform his creative work in the form of dreamlike visions, montage and assemblage, a magical treatment of the figure, and objects that held metaphorical functions.

The Head

The issue of the human head remained a lifelong central subject of research for Giacometti. Above all, the eyes as the core of human life fascinated him to no end. Following the death of his father in 1933, Giacometti made Head-Skull in 1934 and continued to work on many different variations on heads after this. In this period, Giacometti started to work more and more with the concept of scale as well. He wanted to create an exact rendering of his vision, which also included showing the subject at the distance from which he had looked at the subject. One of his first models with whom he experimented with this realistic subject distance was Isabel Delmer. She was the model for one of his earliest miniature figurines, showing her as he saw her from afar in the Quartier Latin.

World War II – Small Sculptures

During World War II, Giacometti returned to Switzerland and lived in Geneva, where he met his wife Annette Arm. In this period, his sculptures shrank in size as he continued to reflect the actual distance between him and his model: between 1938 and 1944, his sculptures had a maximum height of seven centimetres. Reflecting on this development in his art, Giacometti said: “But wanting to create from memory what I had seen, to my terror the sculptures became smaller and smaller.” In 1944-1945, Giacometti created Woman with Chariot, a sculpture from memory of his friend and model Isabel, which would become the prototype for his iconic post-war standing figures.

“Nothing was like what I imagined it to be. A head became an object completely unknown and without dimensions.”

Alberto Giacometti

Breaking Away From the Miniature

After returning to Paris in 1945, Giacometti had a vision that enabled him to break away from the miniature. One day, he was coming out of a cinema on the Boulevard Montparnasse, when he suddenly experienced a complete transformation of reality. He understood that his vision of the world had been photographic up until that moment, though reality was actually “poles apart from the supposed objectivity of a film.”

At this, Giacometti felt that he was entering the world for the first time, observing the many heads around him as though isolated from space. His most famous sculptures emerged from this period. He was now able to work on a larger scale, creating extremely tall and slender sculptures, following from his individual viewing experience. Some of his most well-known works are his Standing Woman and Walking Man sculptures. He returned to these figures again and again, endlessly reworking and repeating the same figures as he wanted to better understand his vision.

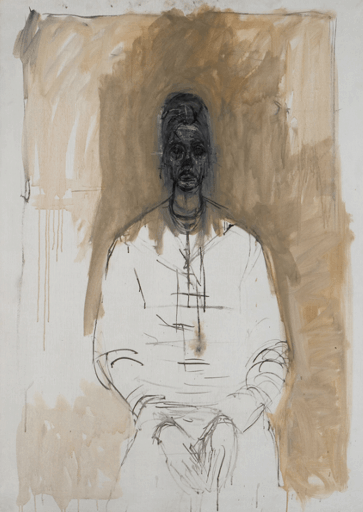

Portraits and Paintings

Although he had always used drawings to accompany the development of his thinking, in the final years of his life Giacometti focused more on painting, producing many figurative paintings alongside his sculptures. He was attempting to capture and render the vibration of the life of his models. His portraits increasingly evolved as the outcome of an ongoing dialogue between painting and sculpture. Giacometti’s favourite models were the people closest to him, such as his brother and assistant Diego, his wife Annette, or his friend Isabel. Occasionally, he painted models he didn’t know well, as long as they agreed to pose for him for hours on end, in challenging conditions. Towards the end of his life, Giacometti worked tirelessly on paintings and sculptures of his wife Annette and his model and muse Caroline, working on Annette all day and Caroline all night. Dramatic, anxious, and full of life, these portraits of the women in his life contained Giacometti’s life-long search for an understanding of the human condition and a representation of the way of seeing the world he had discovered. He died in 1966 from illnesses that were ascribed to years of fatigue, leaving behind incredible works that would immortalise his research into the human condition, suffering and resilience. Sartre once described his walking figures as being “halfway between nothingness and being.” Halfway between nothingness and being, gliding through a sort of intense state of limbo where true experience awaits.

Where to find Alberto Giacometti’s work?

The Giacometti Foundation, established in 2003 with the aim of promoting, disseminating, preserving and protecting the artist’s legacy, holds a collection of around 5,000 works by Giacometti, frequently displayed around the world through exhibitions and long-term loans.

Other works are part of several prestigious collections around the world, from the Art Institute of Chicago to the Fondation Beyeler, Basel, from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Tate Modern in London and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, among others.

Relevant sources to learn more

Giacometti Foundation

Read about Giacometti’s Standing Woman at Museum Berggruen Berlin

Explore the work of other boundary-breaking sculptors

Constantin Brancusi

Anish Kapoor

Henry Moore

Louise Nevelson