Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Guerrilla Girls

By Tori Campbell

“We undermine the idea of a mainstream narrative by revealing the understory, the subtext, the overlooked, and the downright unfair.”

Guerrilla Girls

Who are the Guerilla Girls?

Our “Female Iconoclasts” series highlights boundary-breaking contemporary artists who also happened to be women. They defied conventions in contemporary art and society advancing their industry and pushing the limits of their craft in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to the world. This week, we will focus on the anonymous feminist activist collective the Guerrilla Girls: a group that has shocked and delighted audiences in equal measure by exposing the deeply entrenched gender and racial bias in the art world.

© courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

Biography of the Guerrilla Girls

The birth of the collective

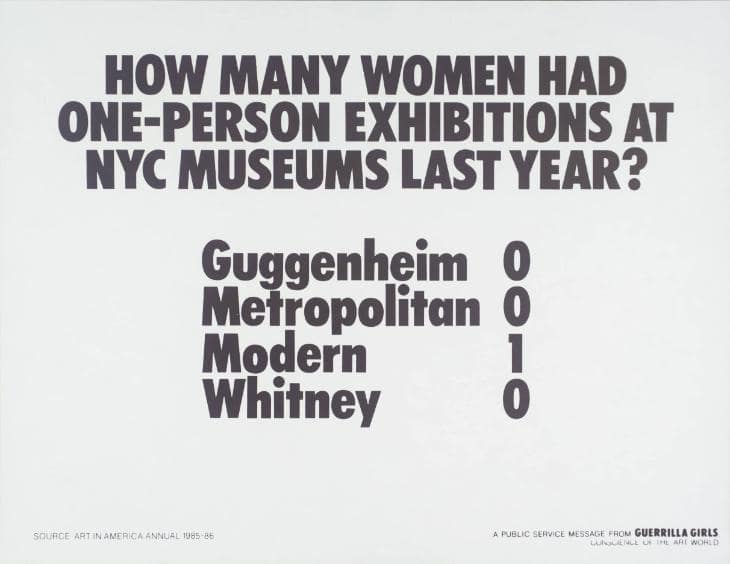

Though museums were unarguably initially founded to uphold colonial power structures by the 1960s, with the Civil Rights Movement and first-wave feminism growing, the all-white, all-male museum boards started to become more obvious and more unacceptable. For a group of female artists, this disparity reached a tipping point, when in the 1985 Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture, among 165 featured artists, only 13 were women.

In response, seven women banded together to found the Guerrilla Girls. Aiming to conceal their identities to bring focus to the issues rather than themselves, the members assume the names of dead women artists (the de facto leaders were “Frida Kahlo” and “Käthe Kollwitz”, with others including “Zora Neale Hurston”, “Alma Thomas”, and “Alice Neel”) and wear gorilla masks in public. Reportedly, the gorilla masks came to be through an initial spelling error, with a member notating them as the “Gorilla Girls” at an early meeting, prompting them to embrace the connotation and don the furry faces when exhibiting or at events.

© courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

“The posters were rude; they named names and they printed statistics (and almost always cited the source of those statistics at the bottom, making them difficult to dismiss). They embarrassed people. In other words, they worked.”

Susan Tallman

Fighting sexism and racism within the art world

The first efforts of the collective focused on the sexist MoMA exhibition of 1985 with protests outside the museum. However, their activities did not gain much traction, so they pivoted strategy to engage in culture jamming, by wheat-pasting posters throughout downtown Manhattan – a tactic that would become synonymous with their efforts.

© courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

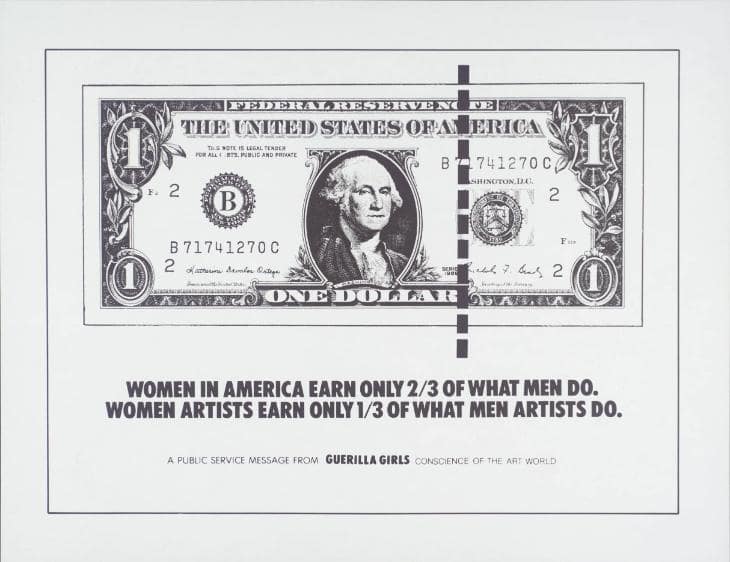

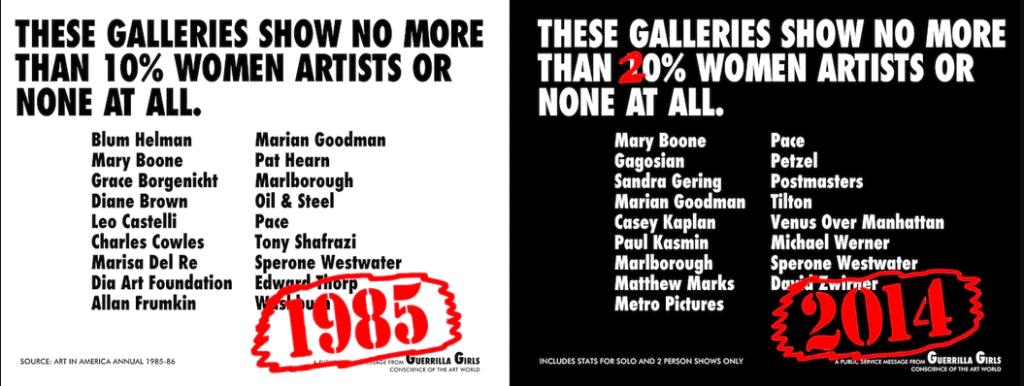

Adept at employing data and statistics to bolster their cases against the mainstream art world, their earliest work is in the form of black and white posters that use tongue-in-cheek humour to display facts about women’s place within the industry. In 1985, they illustrated the salary gap in the art world divided by gender, illustrating that women artists earn only ⅓ of male artists, and attacking the galleries that show just a fraction, or no women artists at all.

Tackling prevailing criticisms of feminism, the group used humour to expand how could feminist art take shape could be with their 1986 work Dearest Art Collector taking the form of a girlish swirling cursive script on baby-pink paper imploring – with cloying politeness riddled with sarcasm – art collectors to acknowledge how few works they collected by women artists.

© courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

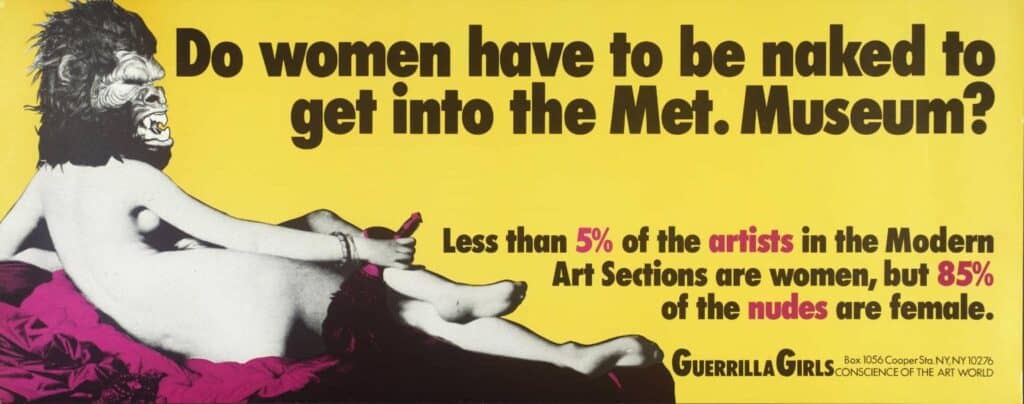

Additionally, in the early years, they conducted what they called “weenie counts”: surveys that included visits to notable institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art where members counted artworks’ male-to-female subject ratios. This data then featured in the groups arguably most famous work that asked sarcastically, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” alongside an image of Ingres’ painting La Grande Odalisque (one of the most famous female nudes of all time) with a gorilla head placed over the original face. The results of the “weenie count” proclaim on the poster that the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s public collections in 1989 showed that women artists had produced less than 5% of the works in the Modern Art Department, while 85% of the nudes were female.

© courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com

Eventually, the group expanded their focus to take on racism in the art world. They aimed to attract artists of colour in order to fight for greater visibility and respect. Their famed Guerrillas Talk Back collection (1985-1990) included works like We’ve Encouraged Our Galleries To Show More Women And Artists Of Color. Have You?, When Racism and Sexism Are No Longer Fashionable, What Will Your Art Collection Be Worth?, and Only 4 Commercial Galleries In NY Show Black Women.

Since the 1990s, the Guerrilla Girls have continued to interrupt and protest inequality and injustice within artistic institutions and politics. Most recently and notably they attended the 2016 Women’s March, carrying signs and distributing pamphlets proclaiming President Trump’s New Commemorative Months.

Additionally, they have focused more energy on the corruption within museum boards through recent controversies such as multiple museum’s ties to the Sackler family, who have actively contributed to the American opioid crisis, and the MoMA trustees’ involvement with Jeffrey Epstein.

Photo by Luna Park, courtesy of Art in Ad Places

“What’s next: More creative complaining!! More interventions!! More resistance!!”

Guerrilla Girls

Controversy and Legacy

The group, while sparking conversation and shedding light on discrimination within the art world, have not been immune to internal controversy as well. In the past, several members have taken issue with the racial makeup of the group, with predominantly white members and non-minority de facto leaders. Additionally, the group often engages with the very institutions they aim to criticize, taking on both public and private commissions while also exhibiting their work at institutions like the Tate Modern, Venice Biennale, Centre Pompidou, and MoMA. Since their debut in 1985, when they were “lauded by the very establishment they sought to undermine”, they have had to play a difficult balancing act that does not always result in their favour.

However, the group has recently taken steps to become more inclusive as they now foster “three separate and independent incorporated groups formed to bring fake fur and feminism to new frontiers: Guerrilla Girls, Guerrilla Girls on Tour, and Guerrilla Girls BroadBand”. The work of the group has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the art world and their three decades of activism have brought more women artists and artists of colour to the fore in galleries and institutions worldwide. They continue to advocate for more representation in the art world and an end to injustices everywhere.

Where to find the work of the Guerrilla Girls?

The collective’s work is currently held in prestigious collections around the world: the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tate Gallery in London, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, among others.

Relevant sources to learn more

Check out the Guerrilla Girls official website

The NYTimes celebrates the Guerrilla Girls 30th anniversary

For previous editions of our “Female Iconoclasts” series, see:

Lousie Bourgeois

Sophie Calle

Marlene Dumas

Yayoi Kusama

Niki de Saint Phalle