Interviews

Artist Interview: Jeffrey Gibson

By Shira Wolfe

“They really are meant to be generous in their communication. There’s no hidden agenda. It’s a mix of directness, beauty, and trying to allow people to be vulnerable to some degree in front of the artworks. “

Jeffrey Gibson

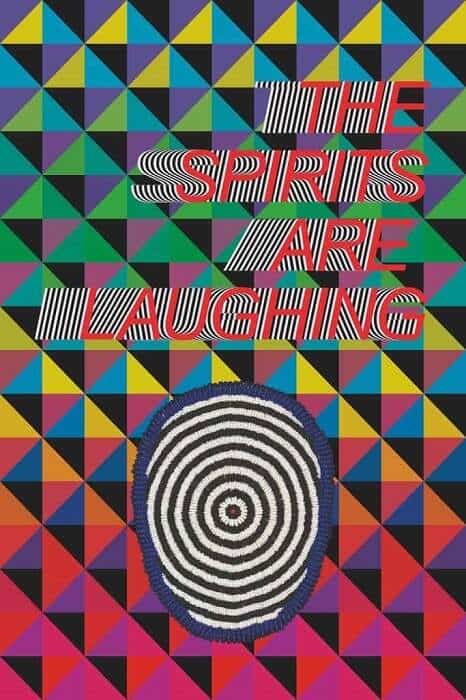

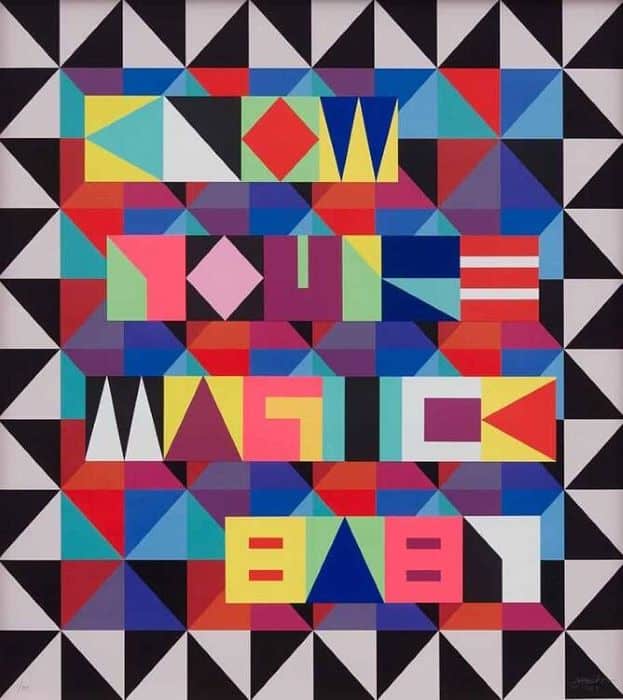

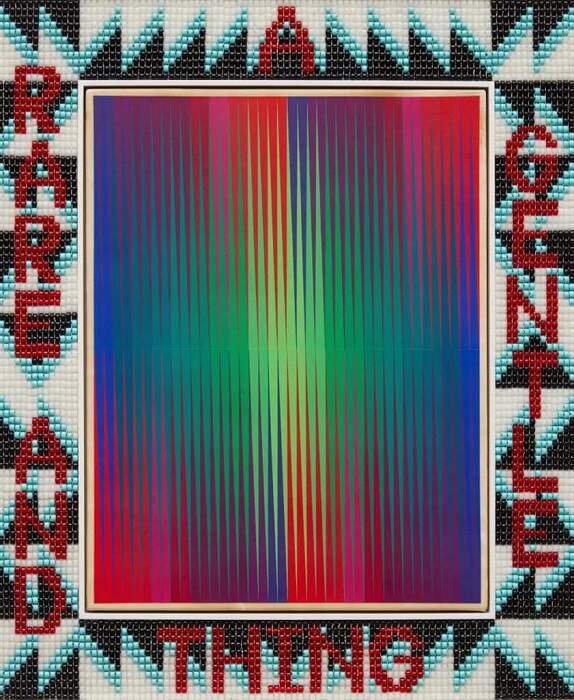

Jeffrey Gibson, a Member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and Half Cherokee, is an interdisciplinary artist based near Hudson, New York. His artworks make reference to various aesthetic and material histories rooted in Indigenous cultures of the Americas, and in modern and contemporary subcultures. Gibson often incorporates laborious beadwork and other fine handicraft in his artworks, as a way to preserve cultural traditions and to counter the eradication of these crafts. Following his recent site-specific exhibition I AM YOUR RELATIVE at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto, we spoke with Gibson about his artistic practice and ideas about the importance of art, community, connection, and healing traumas.

Shira Wolfe: Jeffrey, I’m curious to hear about your first interactions with art, and what inspired you to pursue art yourself?

Jeffrey Gibson: I was really the kid who drew all the time, and my family moved around a lot due to my father’s job. He was a civil engineer with the US government, so we lived in Europe, we lived in Korea, we lived in the US. And the ability to draw was something I was able to take with me. My father traveled a lot for work, and he would always bring me back a poster of an artwork from the museums he visited. I don’t know why he bought me a lot of Matisse posters, but I remember always having a lot of them in my room. And I didn’t realize how large his cut-outs actually were. When I was 15 or 16 I saw one of the cut-outs in person, at the National Gallery in Washington DC, and I remember feeling nauseous, it was just such a shock, going from something I thought was sort of poster-size on my wall, to seeing this entire room filled.

SW: It’s like your version of the Stendhal Syndrome.

JG: Yeah, and I felt so nauseous I had to sit down! So those posters in particular go back to when I was quite young.

SW: When it comes to your art, what are the most important elements in the interaction between the viewer and your art?

JG: I really care that it engages somebody, I do care that there is some level of communication that happens between the viewer and the artwork. And I care that somebody can walk away with some degree of understanding. For me, it’s a marker for when an artwork is complete, and it is a marker for how I determine whether it’s a strong artwork by myself. They really are meant to be generous in their communication. There’s no hidden agenda. It’s a mix of directness, beauty, and trying to allow people to be vulnerable to some degree in front of the artworks.

SW: And did you always have a sense of: “this is how I want to do it, and these are the topics that I want to engage with”?

JG: No, it’s an ongoing process. I taught for nearly 20 years, so I see it from both sides. I think so much of contemporary art thrives on a fatalistic perspective on the world. It’s almost as if students are encouraged to amplify their dysfunction, their pain, their angst. And to me, that’s totally valid, and a lot of my work even begins that way, but in terms of who we can be as humans, I’m interested in working through that and getting to another side.

I don’t like using the word evolution because it’s so loaded, but it is kind of like an evolutionary transformation of strength, of being a feeling person. Somebody who can be intellectual, understand the world in the best way they can, does their best to make sense of it, can share that information, and can move forward from it in support of a better world.

SW: It’s about reaching out to others.

JG: Yes, and you know, for many years I worked as a museum educator. And what we’re talking about a lot now in institutions is, how do we get Native Americans and Indigenous people into institutions? And you have to reflect them in their perspective. We’re still figuring out exactly what that means, but if you give something that people can relate to on a personal level, it feels good. It feels good to stand in front of a heroic image of someone who looks like you. It’s the psychology of visual information.

Acrylic on canvas, glass beads and artificial sinew inset into wood frame. Courtesy of Jeffrey Gibson Studio and Sikkema Jenkins & Co

SW: I’m curious to hear more about that as well. You’re working a lot with marginalized voices and reflecting on the histories of Indigenous cultures in the Americas.

JG: In my generation, when I was in my teens and twenties, so the ‘80s and ‘90s, it was a lot about this idea of representation, women, people of color, queer people… I think we’re past that at this point. It’s not just about representation, it’s also about the content. So it’s not just a visual cue of including people, but there are different ways in which different cultures communicate amongst themselves and with other people, different kinds of spaces where people feel safe to express themselves, feel welcome. And I’m realizing more and more it’s such a hugely radical shift. It’s so deeply embedded, the hierarchy of how different cultural perspectives are positioned.

And it is true, sometimes it’s like if we’re speaking to Black Americans, then we forget to speak to Native Americans because they’re being grouped together as people of color. And even within Indigenous communities, there are hundreds of Indigenous communities that operate independently of each other. It’s the way that we’ve talked about Africa for centuries as if it’s one place, and it’s hundreds of countries. So it’s this tremendously big shift that I think is overwhelming in an interesting way right now.

But I think about who I am speaking to, and it drives a lot of my collaborations. In the collaborations, I invite people who have another kind of knowledge base. We can come together and make something that speaks to somebody more than how I know how to speak to them. And I think I know how to speak to a lot of people. But it is also about dispelling the myth of the independent, singular artist and crediting knowledge. When I know where it’s coming from, it’s not right for me to ascribe myself to someone else’s knowledge, just because I’m the one presenting it.

SW: Could you give some examples of your collaborations?

JG: I’m doing a project right now with the Portland Art Museum in Oregon, and we’re doing a series of glass protest signs that will be projected onto a wall of images with people from the community. And we requested the participation of people who identify as a person of color, Indigenous, or queer. And the day that we shot the photographs, about 90 people showed up. Those are 90 different people, and I gave them the opportunity to present themselves the way they wanted to be presented. People showed up with masks and artworks, wore their traditional regalia; they showed up with their crews, and families… Nobody was generic, nobody was a generalized version of any of those qualifying descriptions. And people were blown away by the images.

Then there’s the performance “To Name Another”, which we did at Site Santa Fe, we’ve also done it at the New Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and at the Esker Foundation in Calgary. Each time, it’s radically different, and we’ve worked with nearly 200 people who have worn the same garments and performed the performance. So as an artwork, the garments have some degree of utility. For instance, there was a trans Dené woman at Site Santa Fe, and I let them choose their own words, and the words were: “They protect the land.” When people are at the microphone, I encourage them to improvise as much as they want. And they continued to go on: “They protect the land, she protects the land, he protects the land, trans people protect the land, queer people protect the land.” And it’s this way that things proliferate so easily, as long as you give people the space.

“There’s so much more to connect about than there is to not connect about.”

Jeffrey Gibson

SW: What drove the site-specific installation at MOCA?

JG: Right now, partially in response to the state of the world, I feel like amidst everybody expressing themselves and protesting, which is certainly important, there is a kind of divisiveness that makes me uncomfortable. I don’t want to become a separatist society. I’m not looking to only be with Indigenous people. Particularly in my family, my husband is Norwegian, and our children are from different backgrounds, so that just isn’t the reality of who we are. So I really wanted the programming that we did for MOCA and upcoming exhibitions to be about this absolute inclusivity.

SW: I think it’s very important that you say this. How can we fight together, how can we continue to connect?

JG: There’s so much more to connect about than there is to not connect about. Obviously, some people may not like me or my politics, and that’s fine, but there still needs to be a place of civility where we can co-exist. That’s what I believe in. And in the art world, it seems like it doesn’t always acknowledge the traumas of what we’re going through right now. But in order to get to that place you have to acknowledge the trauma and work through the trauma, to get to the place where you feel generous enough to give space. You’re still on this side of the trauma if you’re unable to offer space to people that you might disagree with. And the goal is to process it out of your system, to transform it into something that allows you to be the most compassionate person that you can be. Otherwise, you’re not able to grow, you’re not able to heal, it’s literally inside of you and eating away. But you have to find a way to transform it.

And what I’ve been surprised about is how much things like the performances have formed communities, people have expressed this to me. Even at Site Sante Fe, it was interesting because the Indigenous art world lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. But when I was at Site Santa Fe members of the community there kept telling me: “This is a big deal. Indigenous people don’t feel welcome at Site Sante Fe. This is like the contemporary White person’s museum, and now we are invited.” And myself and Nani Chacon took over this whole 20,000 square foot space, and that had never happened before. And that’s crazy. So it means a lot.

SW: And what other spaces do you work in, what about smaller spaces and site-specific work like at MOCA?

JG: Right now I’m involved in three projects. There’s a new ICA opening in San Francisco, and I’ll be in their inaugural exhibition this October. There’s Aspen Art Museum where I’m going at the end of this week to shoot a video, and we’ll do an installation this fall. And then the Portland Art Museum. Those are three projects with large budgets, and they have to exist in a certain way. But I started shooting video in 2015, and video has really allowed me to be able to share work in smaller spaces where the budgets are not particularly large. At MOCA, it was my first chance to work with posters and stickers. It’s a very accessible, popular medium. And it uses all the imagery and objects that have come out of the studio over the past decade and creates a very different kind of exhibition space.

SW: So you made all these artworks beforehand, and then you chose pieces and created these posters and stickers, and that all came together in this site-specific installation?

Yes, and then there are 15 stages that exist in the space, that are moveable. And I have to admit, in the beginning, I just couldn’t comprehend how it was going fill the space or how it would be activated. And that’s why the performances to me were so important because I knew I would be able to activate the space in the way that I would want. But what was surprising was that the public actually really enjoyed using the space, getting stickers that they were allowed to put up wherever they wanted. And people really used the children’s books.

SW: You made a library with children’s books, right?

JG: Exactly. You know, I’m a parent, I have a three-year-old son and a daughter who’s turning six soon. So I know parents who are into the arts. We love spaces where you can take your kids. So from the beginning, I wanted to do something that’s for kids and families. And I couldn’t have articulated it so well before, but it is a part of the audience of the art world that is excluded so often.

SW: That’s well put.

JG: And now I see it’s sort of the same thing in all these other projects I’m working on. My children, my family, my personal life are rarely thought of. It’s kind of like, “Jeff, let’s do this, let’s do that.” And I’m like, “ok, but you have to understand I come with a crew. I’m not going to choose this over my family, so we need to find a way.” And I tell the same thing when I talk to my students. Of course, nobody who doesn’t want to have children has to have children, but don’t sacrifice certain things. Choose your happiness, choose to have a personal life.

SW: So what would be your biggest needs in the coming period, for your creative and your personal life?

JG: I’m at a period right now that I’m busier than I’ve ever been, and the projects that are coming on board are really interesting to me. What I’m probably known for the best are very laborious, time-consuming objects. And that’s still so important for me because it’s counter-intuitive in terms of what’s practical. The studio team and I will spend months working on something, and it’s literally just beading something for months. And when I say it’s impractical that’s kind of a joyful thing for me to say, because the mass-produced world we all live in has eradicated fine handcraft, because it is impractical, and a lot of cultural traditions are lost or stylized for commerce. And so part of my championing craft and in particular artisanal craft is to be counter to that eradication.

The idea with my larger projects is to take concepts that are in the small, beautiful objects I exhibit and expand them to larger spaces. Video is a huge help with that, collaborations are a huge help with that, music and dance are a huge help. Even glass, which expands with light, is a good example. And then of course working with the community. It’s kind of funny, the gallery exhibitions of objects and paintings and sculptures will continue, I love that work, but there’s a back and forth between the larger projects that are not totally object-based, and the object-based work, that benefits each other right now. So what do I need? I need a ton of support, but people are coming through, it’s an interesting moment. And I think Toronto was interesting because I was really surprised and pleased at how much people engaged.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read other interviews on Artland Magazine

Land of Dreams – Interview with Shirin Neshat

Artland Interviews: Jwan Yosef

Stolen Stories: Interview with Ghanaian Artist Kojo Marfo

Other relevant sources

Learn more about Jeffrey Gibson’s upcoming multimedia installation, “the space in which to place me,” debuting at the 2024 Venice Biennale, marking a milestone for Indigenous art through his interview with W Magazine

Jeffrey Gibson, Indigenous U.S. Artist, Is Selected for Venice Biennale

Explore available works by Jeffrey Gibson on Artland

Read more about Jeffrey Gibson’s site-specific exhibition at MOCA Toronto here.

Explore the art of Jeffrey Gibson.

Explore Jeffrey Gibson’s upcoming exhibition at the Portland Art Museum.

Jeffrey Gibson at Aspen Art Museum.

Wondering where to start?