Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Tehching Hsieh

By Adam Hencz

“Life is a life sentence; life is passing time; life is freethinking.”

Tehching Hsieh

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers.

The Taiwanese-American Tehching Hsieh is a pioneer of durational performance art, with fellow performance artist Marina Abramović referring to him as the ‘master’ of the art form. Hsieh is best known for a series of one-year performances he undertook while living in New York from the 1970s onwards: ‘rule-based’ works conducted at the limits of human endurance. Striking in his commitment to these physically and mentally exhausting works, Hsieh nonetheless remained in relative obscurity for the majority of his career.

Arrival In New York

Hsieh spent his childhood in southern Taiwan and even though he avidly read Nietzsche, Kafka, and Dostoevsky, he was a disengaged student and, at age 17, dropped out of school to devote himself to art. He started painting but soon got bored of the limited potential of the practice and decided to try new ways, going on to create several performance pieces after finishing his three years of compulsory military service in Taiwan.

In 1973, as a young artist, he documented his intentional leap from the second floor of a Taipei building, which resulted in two broken ankles. He had not heard of Yves Klein and his Saut Dans Le Vide, and he didn’t know the English expression ‘performance art.’

What he wanted—he declared 20 years later—was to be “a serious artist.”

While working as a seaman, in 1974 for the sake of the continuation of his artistic practice, he jumped ship to a pier on the Delaware River, near Philadelphia, and made his way to New York City. Once there, Hsieh found himself captured by the fatiguing life of an illegal immigrant. With the downtown art scene vibrating around him, he eked out a living at Chinese restaurants and construction jobs, feeling alienated and creatively barren until realising that he could turn his isolation into art.

One Year Performances

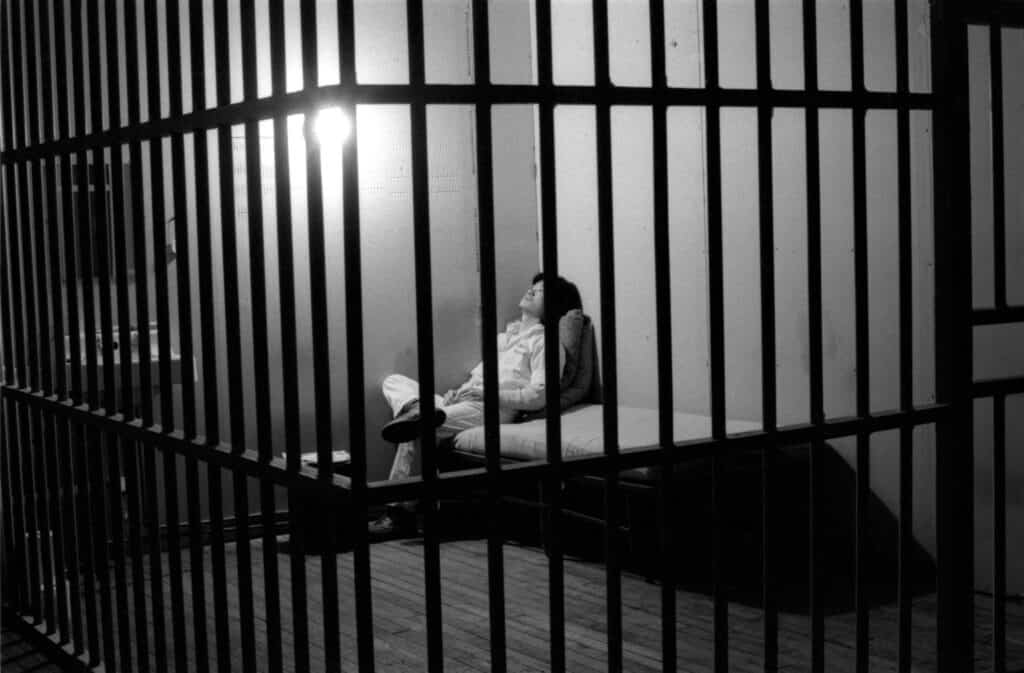

New York art scene began to notice him between 1978 and 1979 when he made the first of his five One Year Performances. “One year is the basic unit of how we count time,” explained Hsieh. “It takes the earth a year to move around the sun. Three years, four years, is something else. It is about being human, how we explain time, how we measure our existence.” Cage Piece started on September 30 of 1978, as Hsieh entered a wooden cage he had built in his loft, and stayed there until September 29 of 1979, in solitude. During that year, he did not allow himself to talk, read, write, or listen to radio and TV. A lawyer, Robert Projansky, notarized the entire process and made sure the artist never left the cage during that one year. His loftmate came daily to deliver food, remove the artist’s waste, and take a single photograph to document the project. In addition, this performance was open to being viewed once or twice a month.

Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly. Photograph: Michael Shen.

Time Clock Piece, his second one-year performance, is today the best known, and its documentation is a curatorial favourite. “While doing one piece, I would think of what to do next,” told Hsieh Marina Abramović in their conversation at Tate Modern. “When I was doing the Cage Piece, I was doing time. I thought I would continue this idea by using a time clock to record doing time. My performance works show different perspectives of thinking about life. But the perspectives are all based on the same preconditions: life is a life sentence; life is passing time; life is freethinking.” For Time Clock Piece, he punched an office timecard every hour, 24 times a day, throughout a whole year, denying himself any real sleep or significant activity. “I was thinking about wasting time. Before I had a studio but I didn’t know what to create. I was just wasting time, thinking, for years. Then I turned wasting time into art.”

From April 11 of 1980, every 60 minutes a sound signal would wake him up to remind him of the task he had self-imposed. At every hour Hsieh, wearing a worker’s uniform, went to a grey-walled room in his Manhattan loft and stamped a time card in a sign-in machine. A few seconds later, a 16mm camera captured a picture of him next to the machine. The film, projected as a motion picture, consequently condenses a whole year into a six-minute piece. In order to complete this performance, Hsieh had to undergo extreme psychophysical stress and to meticulously reorganise his own life around the passing of the hours.

Courtesy Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection, Detroit, and Sean Kelly, New York.

Then came Outdoor Piece, for which he forbade himself to enter any “building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent” from September 26, 1981, to September 26, 1982. He walked and wandered around the city as a pilgrim, on the streets of New York City with just a backpack and a sleeping bag. The only thing separating him from a typical homeless person was a sign hanging from his backpack, specifying the rules of the performance that he had embarked upon.

“I felt depressing after I finished ‘Outdoor Piece’, and I felt the same after the other pieces, because of emptiness as well as having to come back to normal life and dealing with the reality.”

Tehching Hsieh

© Tehching Hsieh and Linda Montano. Courtesy the artists and Sean Kelly, New York.

Outdoor Piece was followed by Rope Piece (1983–84), in which Hsieh and artist Linda Montano spent a full year tied together by the waist with opposite ends of an eight-foot rope. The two artists lived together for a year, but were not allowed to touch one other for the duration of the performance period. “That piece came with a job, and a challenge to deal with society,” said Hsieh. “The job just pays one person and we share half half. She had to take train at 5 o’clock in the morning and teach there and I went too and we shared half [the money].” Then, Hsieh spent a year without having anything to do with art. He denied himself any contact with and refused to talk about art. “I just go in life,” read the artist’s statement. The so-called No Art Piece was then followed by a project spanning thirteen years. For this final, documented piece lasting from 1986 to 1999 (from his 36th to 49th birthdays), Hsieh promised to make art that would never be shown publicly. After 31 December 1999 he pledged never to make art again.

“But I’m not dead yet. I’m still alive. I’m still a witness.”

Tehching Hsieh

Rediscovery

Recognition has come relatively late for Hsieh, who in 2016, at 66 years old described himself as “semi-retired”. Thirty years after his first year-long performance piece, his work was exhibited in 2009 in the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art. His subsequent shift from producing art to publicising and disseminating it also resulted in for example in an exhibition of his work at MoMA in 2009 and in Tate’s acquisition of the Time Clock Piece in 2013. The following year he held an exhibition at Carriageworks in Sydney. In his most extensive retrospective yet, in 2017 at the 57th Venice Biennale, he represented his home country Taiwan in a pavilion that recorded some of his most fascinating and thought-provoking works via an archive of documents, contracts, photographs and maps. “My impression of the Venice Biennale is that it is the Olympic Games of the arts. I’m in the category of marathon,” he told the Guardian in a 2017 interview.

For the Biennale, photographer Hugo Glendinning along with writer and curator Adrian Heathfield filmed a short documentary called Outside Again on Hsieh’s performances, shot in both Taipei and New York. Returning to the original sites of his performances many decades later, Hsieh momentarily relives their sense. Some locations have transformed beyond recognition, some have remained relatively unchanged, and others have fallen into dereliction. The occasion of these returns prompts Hsieh to articulate his thoughts on art and its outsides, long durations, and the testing of human limits. “Since 2000, I have said I wouldn’t create more artworks,” he noted. “But I’m not dead yet. I’m still alive. And I show my work, so that makes me a sub-artist, in my own words. In Taiwan, we often say, ‘I’m just trying to make both ends meet.’ […] But I’m still alive, I’m still a witness, so I can give you all sorts of clues related to this crime scene.”

Relevant sources to learn more

Interview Tehching Hsieh and Marina Abramović in conversation

Iconic Artworks: The Marina Abramovic Performance ‘The House With The Ocean View’

For previous Lost (and Found) Artist editions, see:

Sonia Gomes

Huguette Caland

Ron Gorchov

Samia Halaby