Articles and Features

Pointillism: The Power of Pure Color

By Sara Marín

“Take a few steps back, the technique… vanishes; the eye is no longer attracted by anything but that which is essentially painting.”

Félix Fénéon

Often defined as an art movement, Pointillism is a groundbreaking painting technique that expanded the multiple color explorations introduced by the Impressionists. Initially coined to mockingly refer to George Seurat’s works made of tiny color dots, the term ‘Pointillism’ soon became broadly associated with the work of the Neo-Impressionists and other Post-Impressionism artists.

Science, optics in particular, is at the core of pointillist paintings, which were meticulously planned and executed based on the most recent and innovative color theories at the time – although a few artists would later tend towards a more spontaneous approach, paving the way for the development of Fauvism.

Key dates: mid-1880s – 1890s

Key regions: France

Keywords: painting technique, color palette, dot, science, optics, dot,

Key artists: George Seurat, Paul Signac, Camille Pissarro, Henri Edmond-Cross, Lucien Pissarro, Charles Angrand, Vincent van Gogh, Giovanni Segantini, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo

Pointillism: Definition and Technique

In the mid-1880s, Neo-impressionists started deviating from some of Impressionism’s principles. Although they depicted similar subjects and shared the same goal of Impressionists to render optical phenomena through painting, the group of artists led by George Seurat moved towards a meticulous scientific technique, replacing the fluid and poetic impressionist brushstrokes with small yet distinct dots or patches of pure, unmixed paint.

Pointillism was grounded in the study of optics and relied on the latest theories about color. It is known, in fact, that George Seurat and Paul Signac were familiar with the work of French chemist Michel Chevreul, who presented his research in the book The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours, and Their Applications to the Arts (1855), where he claimed that juxtaposing colors would achieve the maximum luminosity possible. Neo-Impressionist artists translated his ideas into a radical dot-by-dot technique: rather than physically mix different pigments on a color palette – they made them interact optically by means of countless tiny dots on a canvas, creating distinctive homogenous forms if viewed from a distance.

It was the French art critic, editor, and dealer Félix Fénéon who coined both the terms ‘Neo-Impressionism’ and ‘Pointillism,’ describing Seurat’s work as peinture au point.

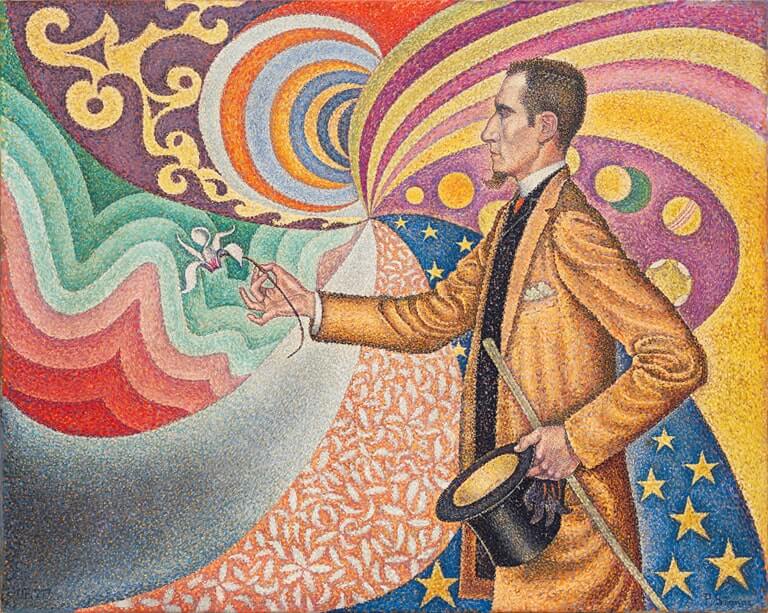

Although Seurat preferred the label ‘Divisionism’ or ‘Chronoluminarism’, it was Fénéon’s designation that stuck. Portraited by Paul Signac in 1890, Fénéon became one of the greatest champions and advocates of Neo-Impressionist artists and their distinctive dotted technique, and without his tireless efforts, we might not know them and their work as we do today.

The Artists of Pointillism and Their Paintings

While George Seurat and Paul Signac were the two main driving forces of Pointillism, many artists embraced the dotted technique to different extents, from the Impressionist Camille Pissarro and his son Lucien to Vincent van Gogh, who embraced Pointillism during his Paris period between 1886 and 1888, but also, years later, artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, and Pablo Picasso at an early stage in their careers.

Around the end of the 1880s, a group of artists in Northern Italy that would come to be known as the Italian Divisionists also started to employ a panting technique similarly rooted in optics and color theories. Among them, Giovanni Segantini, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo and Angelo Morbelli created some of the group’s most notable works, imbued with philosophical and political ideas, as well as mystical arcadian aspirations.

Below is an introduction to the artists who shaped this technique and some of their most recognizable works.

George Seurat

One of the leading artists of Neo-Impressionism and the father of the pointillist technique, French painter George-Pierre Seurat (1859-1891) was born to a wealthy family and was trained in various traditional art schools. Seurat’s first experiences close to Pointillism were in the realm of drawing, especially using conté crayon, until he dived into his well-known large canvases. As for the themes, he predominantly depicted 19th-century France city life and natural landscapes with a predilection for coastal scenes.

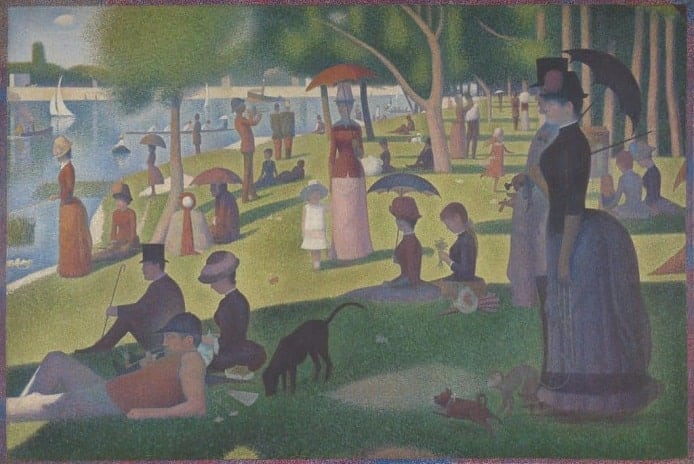

In his brief career, George Seurat created some of the most iconic images of the 19th century, such as Bathers at Asnières (1884) and A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (c. 1884/86). Both paintings moved away from the art canon dictated by the Academy; the former was exhibited at the first show of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1884 – founded that same year by Seurat and Paul Signac, among others – while the latter was included in the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886.

Circus Sideshow (c. 1887/88)

Circus Sideshow (Parade de Cirque) represents a great example of Seurat’s ability to depict moments of leisure. The painting portrays a nocturnal outdoor scene in artificial light: the sideshow of the Circus Corvi at the 1887 Gingerbread Fair in Paris, where free parades and sideshows were performed outside the circus tent to draw passersby in.

Today on view at The Met in New York, the artwork was first exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1888 along with Models, an indoor, daylight scene, which allowed the artist to show the versatility and refinement of his painting technique.

Although not one of Seraut’s most known works, Circus Sideshow has been praised by art historians as one of his most important paintings as it combines formal compositional qualities with the mysterious atmosphere peculiar to the artist’s major canvases.

Paul Signac

Paris-based painter Paul Signac (1863-1935) is, alongside George Seurat, one of the most important artists of Neo-Impressionism. He entered the art world by gathering at Le Chat-Noir cabaret in Montmartre, where he frequented the avant-garde literary circles. Signac had started out as an Impressionist but then moved to the pointillist style ever since he met Seurat – greatly contributing to the technique’s development. After Seurat’s death, Signac played a crucial role in spreading his master’s technique through the theoretical book From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism (1899), which he wrote.

Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde (La Bonne-Mère), Marseilles (1905/6)

Paul Signac was passionate about painting landscapes more than hectic city life. He used a less meticulous style compared to his fellow Divisionist George Seurat, as we can see in Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde, in which rectangular daubs compose a vibrant image comparable to the early examples of Fauvism. The painting shows the artist’s connections with Henri-Edmond Cross and Matisse (who had recently exhibited his ‘proto-Fauve’ painting Luxe, Calme et Volupté). In fact, Signac would become a great champion of Fauvism, especially supporting the work of Matisse. Later in his career, he started sailing around Europe and capturing its landscapes through a bolder color palette, as illustrated by his late watercolors, which he would later translate into large studio canvases painted with vibrant colors and large brushstrokes.

Henri-Edmond Cross

French painter Henri-Edmond Delacroix (1856-1910), who later would change his surname into ‘Cross’ to distinguish himself from the famous painter Eugène Delacroix, moved to Paris from Lille in 1881 and held his first show at the Salon. He was one of the founders of the Société des Artistes Indépendants and became friends with many artists associated with the Neo-Impressionism movement, including Seurat and Signac. However, his transition from the dark tones of Realism to the bright hues of his dotted Neo-impressionist work happened gradually. It was in fact in 1891 – the year of Seurat’s death – that Cross definitively settled in Saint-Clair and began to create his first Pointillist paintings, occasionally traveling to Paris to exhibit his new works at the Salon des Indépendants.

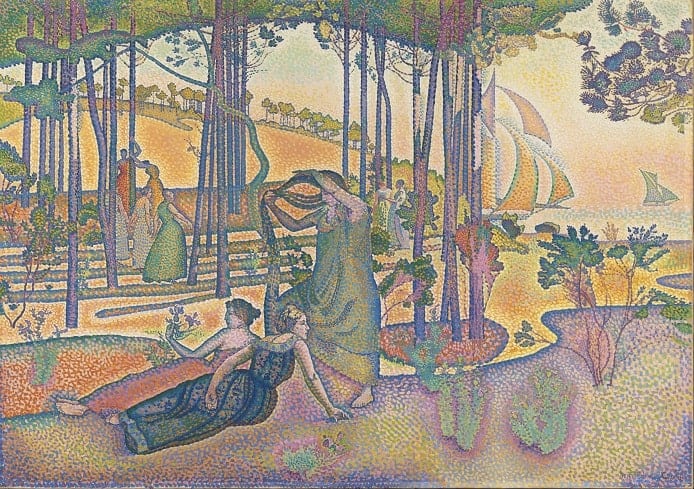

The Evening Air (1893)

After two years in the South of France, Cross had already painted various seascapes – just as Paul Signac was doing – but of all his coastal views, the painting The Evening Air holds a special meaning. The idea for the artwork was conceived at the suggestion of Signac as a decorative celebration of the airy and suspended atmospheres of the French Riviera: Cross decided to paint a group of figures laying in the soft light of the setting sun, arranged in a classical composition. The painting also shows Cross’s transition from using tiny dots of color to larger rectangular brushstrokes that resemble mosaic work and that greatly influenced the Fauves. In fact, Cross gave the painting to Signac, who hung it at his house in Saint-Tropez, where Henri Matisse saw it and used it as an inspiration for his work Luxury, Calm and Voluptuousness.

Camille Pissarro

An advocate of Impressionism for most of his career, Danish-born and Paris-based painter Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) had a short Neo-Impressionist phase. He met young George Seurat at Impressionist events in 1885 and, also encouraged by his son Lucien, he rapidly adopted the Pointillist technique in his own particular way. However, after around one year of experimenting with Pointillism, Pissarro abandoned the technique due to its lack of spontaneity, though some Pointillist aspects, such as the juxtaposition of complementary colors, remained in his later work.

Paysannes ramassant des herbes, Eragny (1886)

Camille Pissarro was an enthusiastic painter of rural landscapes with special attention to people who lived and worked in those lands. In 1884, he moved to the village of Eragny with his family, and the exploration of their new surroundings resulted in a series of country scenes such as Paysannes ramassant des herbes, Eragny – where the influence of Jean-François Millet is evident in the subject. The pointillist technique allowed the artist to cast light and shadows on the meadows with more precision compared to the loose brushstrokes characteristic of Impressionist.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read about related art movements:

Impressionism

Post-Impressionism

Fauvism

Other relevant sources

Check out Michel Chevreul’s digitalized book about color theory