Articles & Features

Portraits of America: Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills

“I wish I could treat every day as Halloween, and get dressed up and go out into the world as some eccentric character”.

Cindy Sherman

As we move into the full swing roller-coaster of election season, with candidates of both stripes seeking to convince the everyman, up and down and across the United States, that they are the best servers and custodians of the nation’s interests, we look at some iconic Twentieth Century artworks, considered, both at the time of their making and today, to be emblematic of American-ness. What that means depends largely on the work itself, and the manner in which the artist has chosen to represent their very own understanding of this notion. Sometimes satirical, often poignant, always compelling, Portraits of America shows us the many faces of a nation that, one way or another, is at the forefront of a global consciousness.

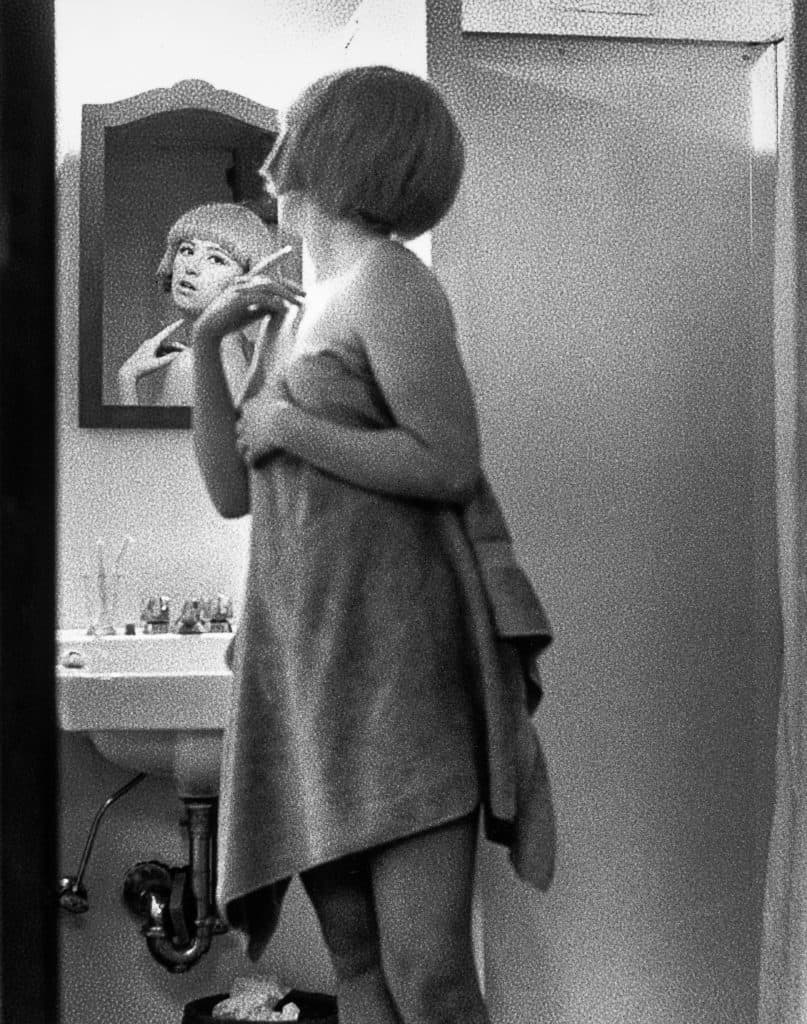

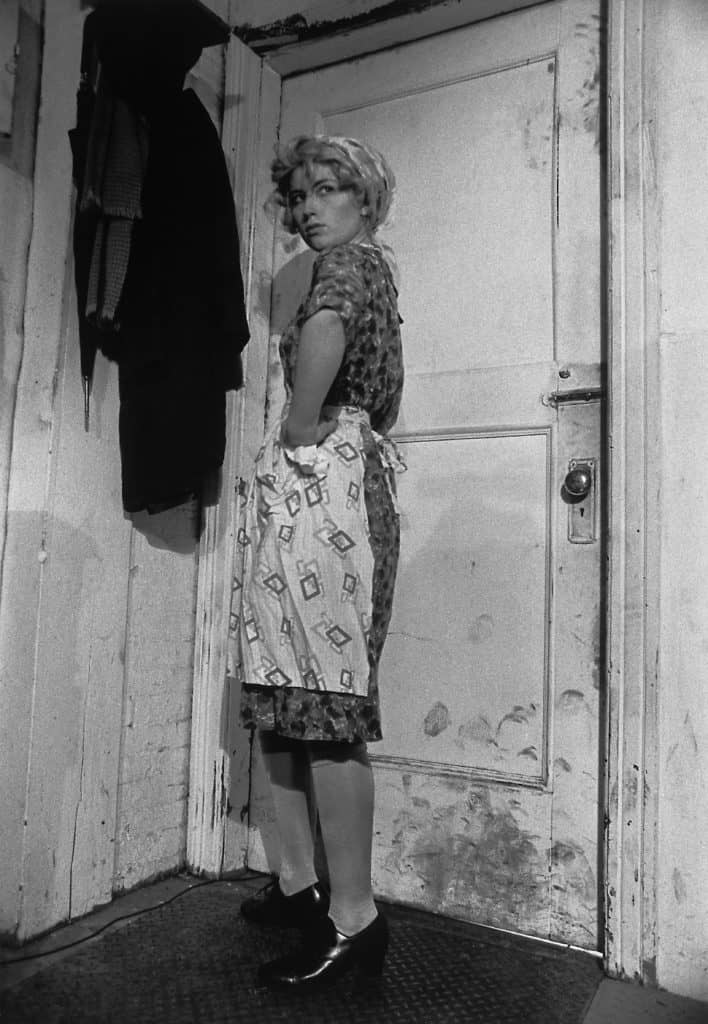

This week, we feature the seminal work of one of the most esteemed American photographers and most influential living artists, that one project that gained its author international recognition: Untitled Film Stills by Cindy Sherman. Not a single picture, in fact, but a seventy photographs suite predominantly realised between 1977 and 1980, this landmark body of work drew upon the vocabulary of popular culture in postwar America resulting in a thoroughly powerful – and still incisive – reflection on the themes of identity representation and stereotypical femininity, not only in the States but in Western culture at large.

“I am trying to make other people recognize something of themselves rather than me”.

Cindy Sherman

The artist

Born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, in 1954 and raised in Long Island, Cindy Sherman studied at the Buffalo University College in New York. She had imagined herself as a painter but soon lost interest in the medium, finding it irretrievably unoriginal. She recalled: “There was nothing more to say [through painting], I was meticulously copying other art, and then I realized I could just use a camera and put my time into an idea instead”. Indeed, that idea has proved to be a valid one. She took her camera and pointed it at herself, a gesture that would become her very signature and also represented the initial step of her quest for the notion of gender and the construction of identity. Already intrigued by costuming and makeup, Sherman began to incorporate these interests into her artistic research and, at the suggestion of Robert Longo – fellow artist as well as the artist’s partner at the time – she began documenting herself dressed up in all manner of disguises.

From that moment on, not only did Sherman pursue her career as a photographer, but, also became almost the only subject of her own pictures – that, however, can be hardly described as self-portraits. On the contrary, she told the New York Times: “None of the characters are me. They’re everything but me”.

Cindy Sherman belongs to the so-called Pictures Generation, a group of American artists raised in the golden era of mass media, the booming Fifties, and come of age in the turbulent and disillusioned early Seventies.

The group, named after a seminal exhibition held at Artists Space in New York in 1977 and titled – indeed – ‘Pictures’, shared a common imagery borrowed from television, advertising, and the movie industry. Finding expression in a wide range of styles and techniques, they were united by the same vocabulary and approach towards mass culture – partly humorous, partly critical.

Throughout her remarkable career, Sherman has transformed herself into countless different personas in an always-compelling illustration of how visual culture shapes appearances, a harsh manifestation of the fictional and grotesque character of today’s media-saturated society. Acting on the intersection between photography and performance, she addressed the themes of gender and societal archetypes as expressed in a number of visual forms, from cinema (Untitled Film Stills, 1977-80) to ageing high society members (Society Portraits, 2008), from pornography (The Centerfolds, 1981; Sex Pictures, 1992) to Old Masters’ portrait paintings (History Portraits, 1988-90), until recent experimentations with social media and the “ugly beauty” of her Instagram selfies.

Untitled Film Stills

Untitled Film Stills consists of seventy 8×10-inch black-and-white pictures: sixty-nine taken from 1977 to 1980, plus one added later to the series.

In each photograph, the artist posed as a different character inspired by female roles in films from the 1950s and 60s; film noir and B-movies, but also Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave. Wearing wigs, vintage costumes, and other props, she impersonated a cast of types or – better – stereotypes, perpetuated by mass entertainment, and especially by Hollywood: from the lonely and unhappy housewife to the ingenue lost in the big city, from the voluptuous librarian to the mid-west cowgirl.

The first six stills, staged in the New York apartment where Sherman was living with Robert Longo, depict various moments in the life of the same character – a blonde actress – while the others explore an array of fictional roles in a variety of locations: interiors, urban as well as rural settings. Therefore not only did Sherman play the double role of photographer and model – or rather director and actor – but also the one of make-up artist, stylist, and fitter.

The first, inevitable reaction to Untitled Film Stills is a sense of déjà vu. ‘I have seen this film before!’ the viewer is bound to think. However, he certainly has not. The artist, in fact, alluded to genres without referencing any recognisable film and, yet, every element – framing, costumes, facial expressions, and so forth – is so embedded in the collective memory that arouses a sense of familiarity. In this regard, acclaimed art historian Rosalind Krauss has described Untitled Film Stills as ‘copies without originals’.

Sherman’s stills are not presented as cinematic shots from a film but mimic instead in visual content, composition, and format, the staged pictures distributed to promote films. Like for classical sculpture, the characters are always immortalised in-between the action, in a moment immediately preceding or succeeding an unspecified event, leaving the viewers open interpretation to imagine possible narratives.

For the same reason, the printed images are glossy and granular, as the artist’s intention was for them to ‘seem cheap and trashy’ look. ‘I didn’t want them to look like art’, she stated. And to emphasise the series’s unambitious quality, the photos were originally sold for fifty dollars apiece. Not even twenty years later, in 1995, the Museum of Modern Art in New York would purchase a complete set for the substantial amount of $1 million, and in 2014 a group of 21 Untitled Film Stills set an auction record, being sold at Christie’s for $6.7 million.

Significance and legacy of Untitled Film Stills

Untitled Film Stills made Cindy Sherman’s name and, although some individual photographs have become more iconic than others, the series in its entirety today represents a modern classic. In its trailblazing simplicity, it shows to what extent visual culture – it was mainly television and cinema at the time, but the range is even wider today – affects our notion of identity and, particularly, femininity. Mass media modes of representation are deeply absorbed in cultural imaginary to the point that identities perceived as original are actually ready-made, and Sherman’s appropriation of visual clichés is so skilful that the viewer recognises as well-known what is, instead, invented. It is arguably in the easy legibility and immediate recognition of generic types that lies the enduring power of Untitled Film Stills.

On the other hand, the stills display a subtle ambiguity as they are explicitly contrived, revealing transparent artifice. Sherman, after all, does not play the generic women but rather actresses playing generic women in a Russian doll of fiction. Her interpretations are purposely theatrical and melodramatic as a metaphor for the artificial character of identities in contemporary culture.

As it often happens when it comes to iconic images, Untitled Film Stills has often functioned as a projection of varied interpretations. In particular, the series has been associated with feminism. Due to its careful analysis of the relationship between image and identity, the project has been interpreted as a critic against mass-media codes of representation of women and their bodies. The scholar Douglas Crimp described Sherman’s work as ‘a hybrid of photography and performance art that reveals femininity to be an effect of representation’.

Sherman, for her part, has never dissociated herself from this kind of reading, though never identifying in the feminist cause the primary reason behind her work.

Interviewed by Betsy Berne for Tate, she once said: “The work is what it is, and hopefully it’s seen as feminist work, or feminist-advised work. But I’m not going to go around espousing theoretical bullshit about feminist stuff”.

Many have also highlighted the relationship between the voyeuristic character of this legendary series and the concept of ‘male gaze’ theorised by film critic Laura Mulvey in 1975. According to Mulvey, women – from literature to visual arts – have always been depicted from a masculine perspective as sexualised objects.

Scholars have wondered if Sherman – acting both behind and in front of the camera – did in fact subvert these codes of representation or rather consolidated them. And, in this regard, she commented: “I know I was not consciously aware of this thing the ‘male gaze.’ It was the way I was shooting, the mimicry of the style of black-and-white grade-Z motion pictures that produced the self-consciousness of these characters, not my knowledge of feminist theory. I suppose, unconsciously, or semi-consciously at best, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women”.

Regardless of Sherman’s position concerning feminism, with Untitled Film Stills, she has undoubtedly created some of the most valuable photographs ever realised, a body of work still compelling and topical. More than forty years after its conception, we can still ask ourselves to what extent is our identity a social construct? What is left of our supposed authenticity when costumes and props are taken away?

Relevant sources to learn more

For previous editions of our “Portraits of America” series, see:

Grant Wood’s American Gothic

You may also like:

Five Photography Monographs Everyone Should Know

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Vivian Maier, Street Photographer

Staged Photography – Top 10