Articles and Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: Primary Structures

“No to transcendence and spiritual values, heroic scale, anguished decisions, historicizing narrative, valuable artifact, intelligent structure, interesting visual experience”.

Robert Morris

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider the history of art exhibitions themselves? Landmark shows of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices.

After a string of shows promoting innovative tendencies either on the one side of the Atlantic or the other, this week we delve into a seminal exhibition which presented the communal trend of a new generation of American and British artists, challenging the traditional notion of art in its every aspect, from the conception of it to its making and display. Held at the Jewish Museum of New York in 1966, Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors documented the rejection of both the expressive and the imitating quality of art in favour of pure, austere volumes, simplified materiality, and absolute absence of representational content.

“Simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience”.

Robert Morris

The background

In the late 1950s, a new generation of artists began to question the painterly subjectivity of Abstract Expressionism, the style dominating the post-war art scene and market with icons such as Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman under the critical guidance of Clement Greenberg.

Following the post-Sputnik era, a wave of new influences led to a renewed interest in Russian Constructivism, with its industrial materials and fabrication; the geometric abstractions of Bauhaus and De Stijl; but also the modularity of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. Artists like Frank Stella, Kenneth Nolan, and Robert Mangold not only did progressively abandon the gestural spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism but painting itself as a medium, pushing the boundaries between various media, and ultimately challenging the conventional notion of art.

Through plain colours, regular patterns, and flat surfaces, they emphasised the materiality of paintings, creating art objects devoid of any reference, symbolism, and meaning.

However, this radical idea of self-referencing art found its best expression in sculpture through the work of Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Tony Smith, and Sol LeWitt, among others.

While Stella’s groundbreaking Black Paintings – a series of concentrical black-and-white canvases – were first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959, and venues such as the Green Gallery, the Leo Castelli Gallery, and the Pace Gallery sporadically showcased the work of these artists in the early Sixties, it was Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors the first show to present a thorough overview of this new, radical tendency.

The show

Kynaston McShine, then Jewish Museum’s Curator of Painting and Sculpture, gathered the works of over forty artists – from well-established figures such as Robert Morris, Carl Andre, and Donald Judd to less known artists as Ellsworth Kelly and Anthony Caro – and presented the public with what he used to define ‘New Art’ from April 27 to June 12, 1966.

Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptures shocked both audience and critics with hard-edged volumes, plain-spoken materials, modular compositions, and monochromatic colours.

Viewers, accustomed to contemplate idiosyncratic gestures and expressive excess, found themselves dumbfounded in front of sculptures intentionally anonymous and demanding interaction. Partly influenced by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s The Phenomenology of Perception (1945), the show presented a radically new idea of artworks merely as objects occupying space and put a new emphasis on the physical environment surrounding them.

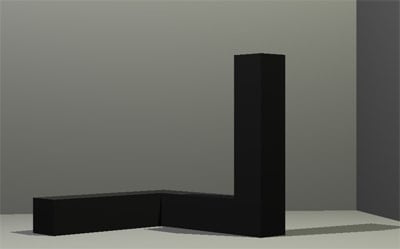

Robert Morris stated that he intended to make sculpture “a function of space, light, and the viewer’s field of vision […] for it is the viewer who changes the shape constantly by his change in position relative to the work. […] There are two distinct terms: the known constant and the experienced variable”. His idea materialised in Untitled (L-Beams), one of the most audacious entries in the show. Three L-shaped solids, identical in shape but arranged differently on the floor, prompted gallery visitors to notice – moving around the sculpture – how the perception of objects changes in relationship to someone’s perspective.

Carle Andre’s Lever, a line of 137 firebricks projecting out from the wall, acted similarly, representing an unexpected interruption on the visitors’ path and also drawing attention to the materiality of the work. “My ambition as an artist – he stated – is to be the ‘Turner of matter’. As Turner severed colour from depiction, so I attempt to sever matter from depiction”.

Minimalism: ‘What you see is what you see’

The style that Kynaston McShine had identified as ‘new art’ was later dubbed ‘ABC Art’, ‘Object Art’, ‘Cool Art’, but also ‘Reductive Art’ and ‘Literalism’; however, it was ‘Minimalism’ the term that prevailed.

Minimal artists challenged the supremacy of painting, and deprived art of any connotations, whether descriptive or symbolical, except for its physical presence in space determined by materials, form, and scale.

Carl Andre referred to his work as ‘plastic poetry’, while Donald Judd used to call his works neither paintings nor sculptures, but ‘specific objects’.

Artists associated with Minimalism used deceptively simple shapes – indeed, primary structures – repetitive motifs, non-hierarchical compositions, and materials that require no manipulation from the hand of the artist – such as fiberglass and aluminum – relying on industrial technologies instead.

As Donald Judd explained in his seminal essay, Specific Objects: ”When an artist uses a multiple modular method he usually chooses a simple and readily available form. The form itself is of very limited importance; it becomes the grammar for the total work. In fact, it is best that the basic unit be deliberately uninteresting so that it may more easily become an intrinsic part of the entire work. […] Using a simple form repeatedly narrows the field of the work and concentrates the intensity to the arrangement of the form. This arrangement becomes the end while the form becomes the means”.

Recognition and legacy

Primary Structures is credited with introducing Minimalism to the American audience but also with launching the movement on the international stage. Poet John Ashbery, in his review for ARTnews Young Masters of Understatement, described the show as making “a brilliant case for this hitherto diffuse and largely undocumented school”.

Despite some criticism, in primis by formalist critic Michael Fried, the show turned to be a success. Debates followed over the artist’s and the viewer’s role in the creation of meaning, leading to significant steps towards the development of conceptual art. By the end of the decade, numerous variations on the Minimalist approach had sprung up in both the US and Europe, from the Californian Light and Space movement to the Italian Arte Povera, also bleeding into the realm of fashion design, music, and theatre.

In 2014, the Jewish Museum re-examined the show from a global perspective with Other Primary Structures. Featuring sculptures by artists working in the 1960s in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa, the show presented a non-western alternative to the seminal 1966 exhibition, remarking – almost fifty years after its occurrence – the show’s prominent place in the post-war contemporary art scene.

Relevant sources to learn more

Agents Of Change: Plastic. Or How Plastic Became An Era-Defining Material

Dan Flavin – Pioneer of Minimalism Through Light

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

This Is Tomorrow

The Ninth Street Show

The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938