Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The Armory Show

“[The show will be] the most important public event…since the signing of the Declaration of Independence. (…). There will be a riot and a revolution and things will never be the same afterwards”.

Mabel Dodge

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider art exhibitions? It is an inescapable fact that the landmark exhibitions of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history almost as much as any other single determining factor, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices. This week we feature the International Exhibition of Modern Art, held in New York in 1913. Better known as The Armory Show, it introduced the groundbreaking European Avant-garde to an astonished American audience to the point that rarely – perhaps never – did an exhibition represent such an epoch-making event.

“To be afraid of what is different or unfamiliar, is to be afraid of life, and to be afraid of life is to be afraid of truth”.

Catalogue of the Armory Show

The background

At the turn of the twentieth century, New York was rivalling Paris as the modern city par excellence. However, the American industrial and technological advances – with the consequent revolution in transportation and communication – could not compete with the French capital’s cultural vitality and experimentation in visual arts. Even though a few pioneering exhibitions at Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 had been featuring examples of European modernism since 1902, Americans were still accustomed to the orthodox Gilded Age realism: moral values and the mimetic representation of nature were the cornerstones of artistic production.

Commercial galleries and juried exhibitions at the National Academy of Design used to promote this rather conservative style causing discontentment amongst a small coalition of innovative artists who saw their work regularly omitted.

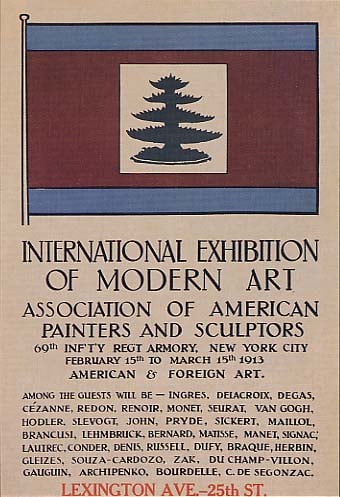

Driven by the disappointment at being constantly rejected, in December 1911 this forward-looking group founded the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (A.A.P.S.) with the express purpose of “leading the public taste in art rather than follow it” by showcasing “the works of progressive and live painters, both American and foreign; favouring such work neglected by current shows”. The Association would not last five years, ending in early 1916 among mutual accusations and power struggles. However, it could boast the production of the 1913 Armory Show; in fact, just one exhibition – yet a legendary one.

The main characters

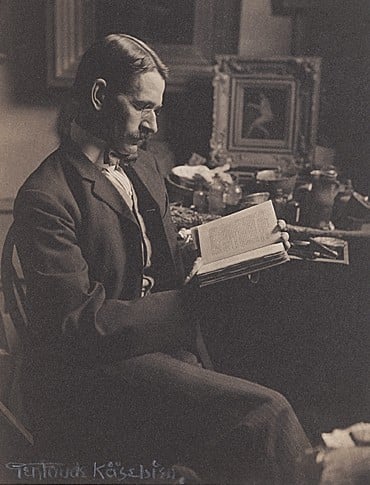

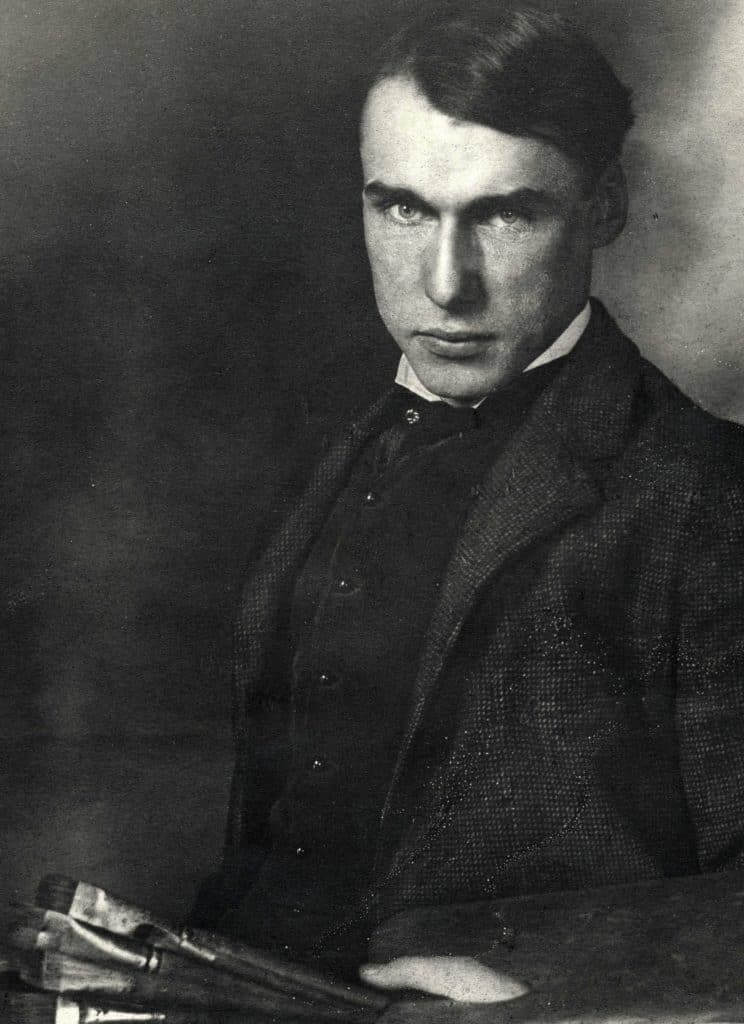

Members of the A.A.P.S. board became the key players in the Armory Show: in particular Arthur B. Davies, president of the association, and Walt Kuhn, the secretary.

Davies undoubtedly proved to be the driving force behind the exhibition, earning a number of supporters as well as detractors. Some praised his dominant leadership, while others perceived it as arrogant and manipulative. Regardless, he secured the funding essential to make the show possible thanks to his connections in the art field.

Kuhn recalled that “When money was needed, it was produced from the sleeve of Arthur B. Davies… He financed the show – he and his friends”.

As for Kuhn, he defined himself as the Armory ‘showman’; nowadays, he would be probably called ‘head of marketing’. For some time, his Story of the Armory Show, published in 1938, was the main account of the event and it is now common belief that he took perhaps too much credit for selecting works and organising the show. However, if his knowledge of modern art was not as sophisticated as he claimed, Kuhn did an excellent job with advertising and promoting. He corresponded with newspapers, designed the celebrated pine tree logo, printed campaign buttons and posters, papered the city.

Both him and Davies spent months travelling across Europe visiting galleries, collections, and studios to perform the unwieldy task of securing art for the show. They dealt with loans and shipments to New York, largely supported by American artist and critic Walter Pach who acted as a European Agent for the exhibition, being by far the most familiar of the group with avant-garde art.

Despite how deservedly – or undeservedly – they took credit for setting up the show, they cannot be accused of being self-serving and taking advantage of the event to showcase their own work. In fact, it was theirs in the first place that showed the stylistic influence of European Modernism in the immediate aftermath of the Armory Show. Their intentions were sincerely didactic, and – even though today the idea of art as an evolving progression is considered rather misrepresenting – the organisers were willing to lead the public along a path through the history of modern art rather than to shock the audience.

On the other hand, they were well aware of what they were doing and its groundbreaking extent. It was Kuhn who stated: “We will show New York something they never dreamed of”. For sure, the uproar that followed did not take them by surprise.

The show

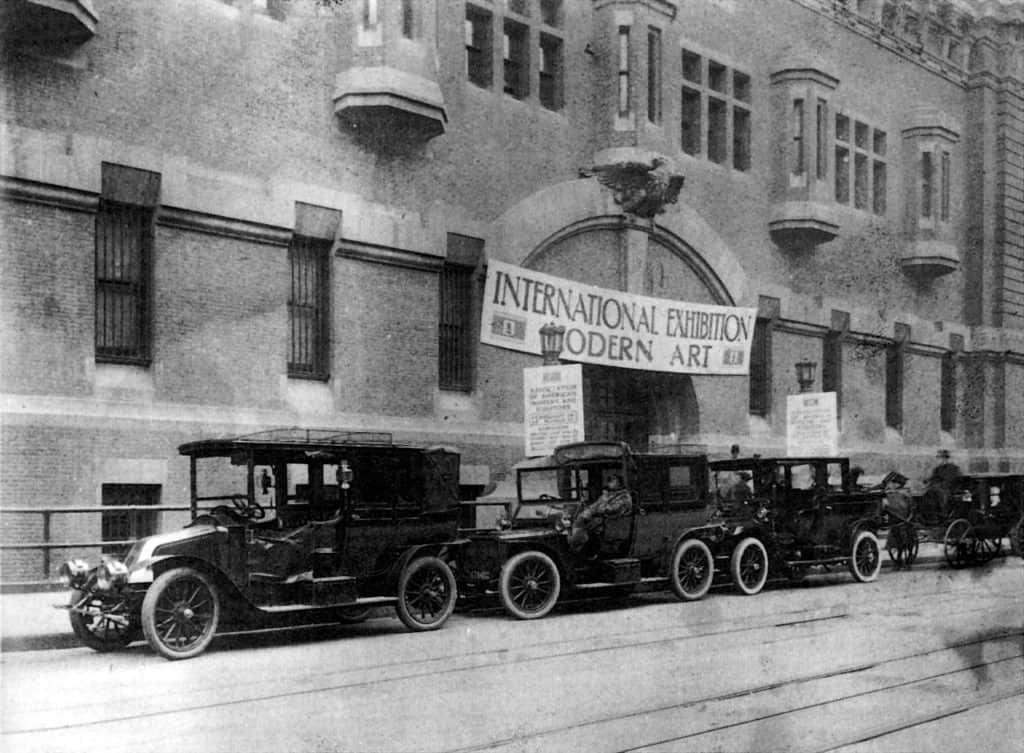

The 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, selected as the venue for the exhibition, gave the show its legendary name and, on February 17th, 1913, opened its doors to welcome the first 4000 guests of the over 85,000 that would visit the show during its month-long run. It was a show of giant proportions, the largest of its kind ever mounted in the United States, with more than 1300 works showcased, by both American and European artists. It included paintings, sculptures, and decorative art.

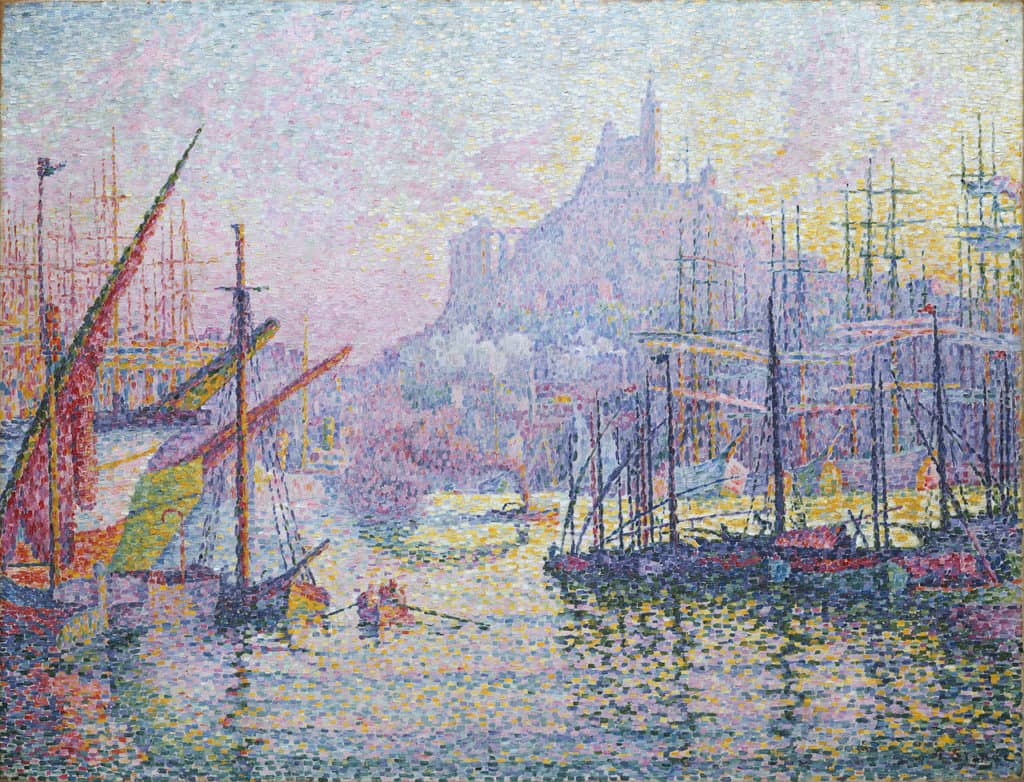

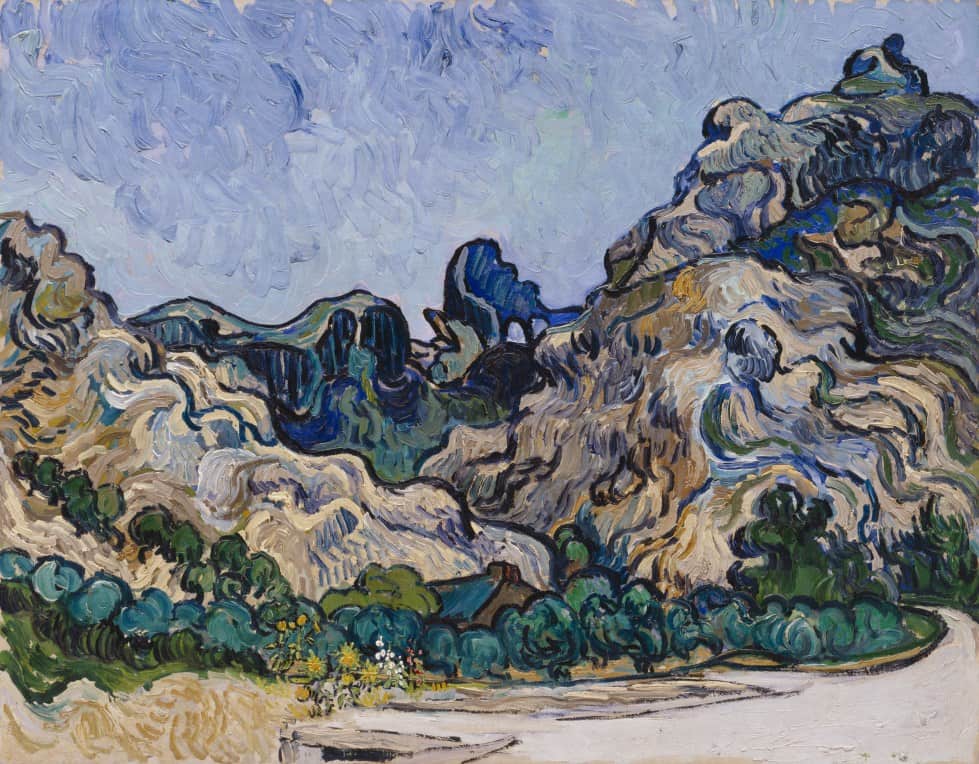

Inside, the vast space of the Armory was partitioned into eighteen octagonal galleries surrounded by burlap covered walls; garlands, and streamers hung from the ceiling. The visit was conceived to start with American sculpture and then to progress chronologically. Implying an evolutionary sequence, the central galleries (two of the four aisles leading from the front galleries to the rear) featured nineteenth-century French art masters like Delacroix, Ingres, Courbet, then proceeded with Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, ultimately culminating with the Avant-garde – in particular Cubism and the work of Matisse.

American artists – among which stood out Albert Pinkham Ryder, Robert Henri, and George Bellows – were relegated to the margins, causing a certain resentment and complaints among A.A.P.S. members who interpreted the arrangement as a sabotage.

After New York, the exhibition travelled to the Art Institute of Chicago attracting even larger crowds (almost 190,000 visitors) and then to the Copley Society of Art in Boston in a generalised lack of enthusiasm with not even 15,000 guests. Eventually, the works went back to galleries, artists, previous as well as new owners as 275 pieces were sold at all three venues.

Controversy and recognition

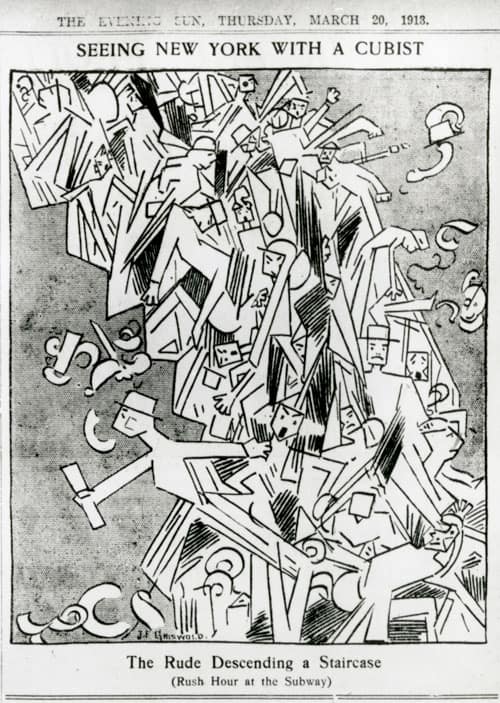

The show’s reception was varied. Some were positively shocked and considered the event as a revelation. Others condemned it, crying scandal. Former President Theodore Roosevelt concisely commented: “That’s not art!”. Some others were sincerely amused, as also showed by the number of parodies and mocking commentary appeared in the local press at the time. The Chicago Tribune reported: “The crowd hurries first to the Cubist and Futurist room, eager to know the worst. There, most of them are obliged to laugh, others are struck dumb with an open mouth stare, and a few are seized with deep despair”.

All in all, the exhibition turned out to be a resounding success: attendance was heavy; artworks were sold. All of a sudden, the entire public attention was on the art world and everyone seemed to have an opinion about the recent developments in the arts. Since then, American art history has been divided into two distinct periods: before and after the Armory Show.

Even though the initial purpose of the exhibition was to offer American artists an independent alternative to display their work, it was the radical European Avant-garde to inflame the audience. Cubists’ synthetic style and Fauves’ bright, unrealistic colours totally outshone the rest, to the point that, when the exhibition went on show in Boston, because of a lack of space all the pieces by American artists were excluded.

Among the others, two paintings caused a sensation becoming the Armory’s lightning-rod main attractions: Matisse’s Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), with its vivid, improbable colours and bold brushstrokes; and Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2. The latter, combining the Cubist depiction of space with the Futurist representation of time – which simultaneously captures multiple moments – disoriented the public and became a widespread subject of ridicule. Art critic Julian Street famously described it as “an explosion in a shingle factory”.

The Armory Show’s reputation grew steadily to occupy a legendary status. In 2013, many institutions celebrated its centennial with exhibitions and publications; the Montclair Art Museum, the New York Historical Society, and the Art Institute of Chicago among the others. Moreover, a documentary film has been realised, entitled The Great Confusion: The 1913 Armory Show.

The legacy of the Armory Show

In spite of the critiques that considered the great interest towards European art intimidating and unfair, the Armory Show caused the opposite effect, catalysing the American art world instead. A number of progressive artists like Georgia O’Keeffe, John Marin, and Edward Hopper – who made his very first sale at the Armory – felt encouraged in pursuing experimental paths, supported by new modern art galleries opening in New York, as well as by American collectors who began purchasing American avant-garde pieces. But private dealers and collectors were not the only ones with a new desire to integrate recent artistic experiences into their collections. At the show, non-other than the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Paul Cézanne’s Hill of the Poor (View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph), the first substantial entry of its major modern collection.

The rise of New York as a main centre of the art world also contributed to establishing a crucial connection between the sides of the Atlantic. Especially in the 1930s, influential artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Mark Rothko, Piet Mondrian, Marc Chagall, Louise Bourgeois, and many others fled Europe and settled in the United States setting up a two-way exchange of creative ideas that would be the basis for further groundbreaking developments.

The innovations introduced by the Armory Show not only have impacted the art market and the visual arts but public taste in its entirety. The event accelerated the development of a generalised modernist culture, with blurred partitions between the arts, setting the stage for breakthroughs also in literature, photography, and music – one just has to think of the emergence of Jazz in the 1920s. Essentially, the show presented the possibility of a new aesthetic, dispelling the idea of beauty – in the broad sense – as necessarily dependent on reality and morality.

Relevant sources to learn more

1913 Armory Show: The Story in Primary Sources. Documents, letters and pictures digitally exhibited by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

The Salon Des Refusés

The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’