Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Niki de Saint Phalle

By Shira Wolfe

“I started painting in the madhouse, where I learnt how to translate emotions, fear, violence, hope and joy into painting. It was through creation that I discovered the sombre depths of depression, and how to overcome it.”

Niki de Saint Phalle

Who was Niki de Saint Phalle?

Artland’s “Female Iconoclasts” series celebrates female artists who were among the most boundary-breaking iconoclasts of our time; women who defied conventions in contemporary art and society in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to the world. This week, we explore the monumental feminist, performative sculptural works by Niki de Saint Phalle, a French-American artist who lived a tumultuous life, found her saviour in art, and defied artistic conventions from the get-go.

Biography of Niki de Saint Phalle

Niki de Saint Phalle was born in France as Catherine-Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle on 29 October 1930. Her mother was an American, her father a Frenchman. Her wealthy family lost their business and fortune in the stock market collapse and she spent most of her childhood and adolescence in New York City, where her family moved after losing the business. She was a temperamental teenager, getting expelled from school for painting the fig leaves of the school’s classical sculptures red. Later in life, she would reveal a traumatic childhood secret, namely that her father had sexually abused her repeatedly since the age of 11. This caused her to be unstable and troubled, and she would eventually deal with this trauma through her art.

Saint Phalle married young, at the age of 18, and the couple eventually moved to Paris with their first child. She suffered a nervous breakdown at the age of 22 and was sent to a psychiatric hospital in Nice where she received electroshock treatment. While in the hospital, her doctors encouraged her to paint, and she started devoting herself to art. She said of this period: “I started painting in the madhouse, where I learnt how to translate emotions, fear, violence, hope and joy into painting. It was through creation that I discovered the sombre depths of depression, and how to overcome it.” Art saved her, helping her to process and overcome her mental trauma through painting and sculpture. The young woman was completely self-taught and was encouraged by her friend, the American-French painter Hugh Weiss, to continue painting in her genuine style.

Gaudí, Tinguely, and a Life Devoted to Art

In 1955, Saint Phalle and her family moved to Mallorca, where she discovered the work of Antonio Gaudí in Spain and was particularly moved by his Park Güell in Barcelona. From this, the idea was born to someday create her own sculpture garden, and she became inspired to use found objects and a diverse range of materials in her art. Another important moment was her meeting with the Swiss kinetic artist Jean Tinguely in Paris in 1956. In this period, she attempted her first large-scale sculpture, enlisting Tinguely’s help. In 1960, she decided she wanted to devote her life entirely to art, separated from her husband and moved in with Tinguely, who had separated from his wife. The couple collaborated closely on projects, participated in exhibitions and happenings in California, Nevada and Mexico, married in 1971, and divorced two years later. Despite their frequent disagreements, the two artists continued to collaborate until Tinguely’s death in 1991.

“In the human heart there is an urge to destroy all. To destroy is to affirm one’s existence in the face of and against everything.”

Niki de Saint Phalle

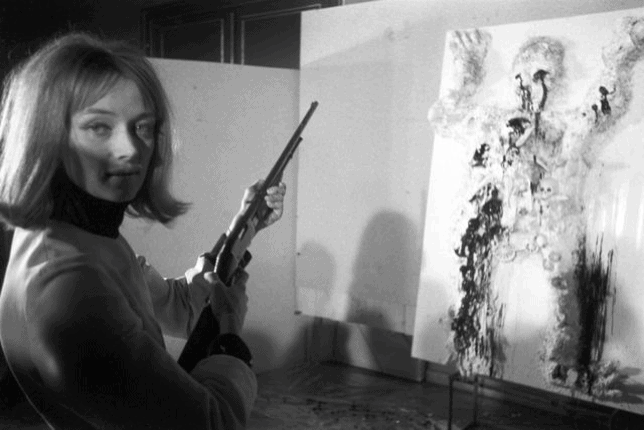

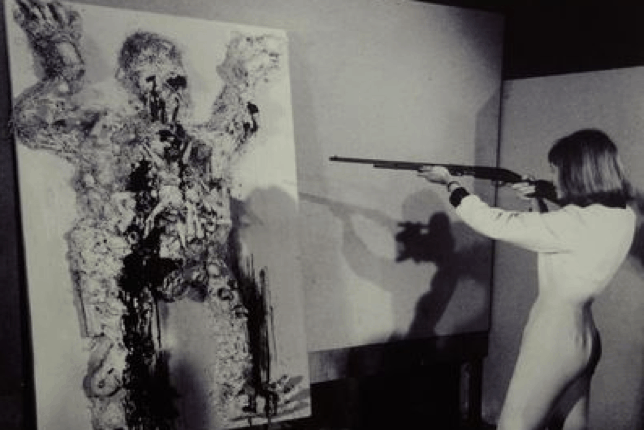

Les Tirs paintings

In the early 1960s, Saint Phalle began creating her first “shooting paintings”, Les Tirs (‘the shots’): complex assemblage-works with concealed paint containers that she would shoot at. The impact of the shots created spontaneous effects, intensely charged explosions of colour. She had her first exhibition of the Les Tirs paintings in 1961. These works made her famous and provided her with an outlet for the difficulties she had faced throughout her life. Around this time, she became a member of the Nouveau Réalisme group, which included Jean Tinguely, Christo, Arman, Yves Klein and Jacques de la Villeglé.

Niki de Saint Phalle’s Nanas

The artist created her first Nanas in 1965. “Nana” is a slightly derogative French term for a young girl. Her Nanas are large-scale, brightly-coloured archetypal female sculptures, inspired by the artist’s friend Clarice Rivers, who was pregnant at the time. The Nanas were voluptuous goddess-like creatures, triumphant, enduring symbols of femininity and maternity. Initially, she used fabric and found objects for the Nanas, and later on began introducing polyester to achieve a more plump, vibrant effect. She even designed inflatable Nanas, which were produced and distributed in the United States.

Arguably the ultimate Nana was Hon, a monumental sculpture created with Jean Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvel, which was exhibited at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1966. She filled an entire exhibition hall, and though she was destroyed at the end of the exhibition, this Nana is remembered as the ultimate empowering female figure in art history. Saint Phalle continued to create Nanas all her life and would also influence her lifelong Tarot Sculpture garden project in Italy.

Daddy

Though she was mainly engaged with sculpture, Saint Phalle also continued to paint and even made movies. Her film Daddy (1973) uses autobiographical material criticising her family and dealing with her childhood trauma. In the film, she is attacking a figure reminiscent of her father, as such providing an outlet for her anger and suffering. The film was made in collaboration with filmmaker Peter Whitehead, known for his sexually liberating and forward-thinking films.

Le Jardin des Tarots

In 1979, the artist began to realise her lifelong ambition inspired by her visit in 1955 to Park Güell. She wished to create her own magical place, a public park based on the Tarot deck, which was to be monumental in scale, filled with colours and imagination. She wanted to prove that a woman was just as capable as a man of producing such an ambitious large-scale work. When she was offered a parcel of land for her sculpture garden in Garavicchio in Tuscany by a friend, she set to work.

The monumental sculptures, inspired by Tarot cards, resulted in large ceramic, mosaic and glass figures of up to fifteen metres high. The artist even had her own residency built into The Empress, a building in the park designed in the shape of a sphinx, which she moved into in 1982. “At last,” as one of her quotes reads, “my lifelong wish to live inside a sculpture was going to be granted: a space entirely made out of undulating curves… I wanted to invent a new mother, a mother goddess, and be reborn within its form… I would sleep in one breast. In the other, I would put my kitchen.”

The artist first made models of the figures for her Tarot Garden and laid the foundations in 1978. Construction started on the first sculpture, The High Priestess, in 1980. This sculpture represented female creativity and strength. Throughout the intensive project, she received a great deal of assistance from friends and supporters from all over the world. As such, it became a great collaborative work. She explained: “The Tarot Garden is not just my garden. It is also the garden of all those who helped me make it.” The massive undertaking would take almost 20 years – the sculpture garden was opened to the public in 1998.

Life and Death from Art

In an ironic twist of events, art, the very thing that had saved Saint Phalle’s life, also ended up killing her. For years, she had worked with various materials that violated health and safety rules, which meant inhaling toxic fumes on a daily basis. As a result, she suffered from inflamed lungs, destroyed by the polyester dust from her sculptures. In 2002, at the age of 71, the artist died from respiratory failure.

All her life, the artist had campaigned against social injustices, racial segregation, women’s lack of rights, and against the stigmatization of people with AIDS. Her art was an ode to female strength, both sensual and empowering. It criticized conservative values and celebrated the full, brilliant, versatile spectrum of human beings.

Where to find Niki de Saint Phalle’s work?

The artist’s archives and artistic rights are held by the Niki Charitable Art Foundation (NCAF) in Santee, California; but many of the monumental sculptures by Saint Phalle and are exhibited in public places across the globe. The largest holdings of her works belong to The Sprengel Museum in Hanover and MAMAC in Nice, while the Swiss city of Fribourg boasts the Jean Tinguely–Niki de Saint Phalle Museum, entirely dedicated to the artist couple’ works.

Relevant sources to learn more

Niki de Saint Phalle Charitable Art Foundation

For previous editions of our “Female Iconoclasts” series

Lousie Bourgeois

Sophie Calle

Marlene Dumas

Zaha Hadid

Yayoi Kusama