Articles and Features

Alphonse Mucha: The Artist Behind the Iconic Art Nouveau Posters

“The purpose of my work was never to destroy but always to create, to construct bridges, because we must live in the hope that humankind will draw together and that the better we understand each other the easier this will become.”

Alphonse Mucha

This article explores the life and artistic development of Czech-born artist Alphonse Mucha, Art Nouveau painter, illustrator, and graphic artist. One of the most celebrated figures in turn-of-the-century Paris, Mucha became distinctive in the history of art for his stylized and decorative aesthetic and a strong portfolio of works in illustration and commercial art. His work and artistic vision shifted the concept of poster from just advertising to an art form in its own right, producing legendary images that would define an era. Furthermore, Mucha left a strong mark in Slavic art as he devoted a big portion of his paintings towards depicting the history and the importance of Slavic cultures.

Alphonse Mucha’s childhood and early years

Alphonse Mucha was born on July 24, 1860, in the small town of Ivancice in southern Moravia – then a province of the Austrian Empire, nowadays part of the Czech Republic. Mucha grew up in a modest family, the oldest of 6 kids. Due to the family’s difficult financial situation, his parents couldn’t afford to support Mucha’s education after elementary school. However, the young Mucha was showing an early interest and talent in visual expression, and especially in music, which allowed him to pursue his education in a gymnasium in Breno, where he was sent to sing in a church choir. There, he was educated in a very religious and nationalist environment, which would reflect in his later artistic work. In Breno, Mucha started designing flyers and posters for patriotic rallies. After finishing high school, he tried to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague with no success and therefore decided to move to Vienna. In the capital, he managed to get an apprenticeship as a scenery painter for theatre and joined the city’s vibrant art scene, mainly earning money from occasional portraits commissions.

While he was working as a painter around Austria, Mucha met with Count Eduard Khuen Belasi, the nobleman who would become his main patron. Impressed with Mucha’s talent, Belasi encouraged him to move to Munich and enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts. Even though there are no recordings of Mucha actually studying at the Academy in Munich, he managed to get to know a number of successful Slavic artists there and build a strong community around himself. Although he enjoyed his time in Munich, he soon had to move out of the country, because of the tight political situation in Bavaria. In 1887, at the suggestion of his trusted friend and patron Belasi, Mucha moved to Paris.

Recognition in Paris

In Paris, Mucha took two years of additional art education, befriended other artists, and started to get noticed. When Belasi stopped supporting him financially, Mucha had already become an established figure amongst Parisian creative and artistic circles: getting job opportunities was not a challenge anymore.

Mucha’s iconic Art Nouveau posters

He started making illustrations for the weekly magazine La Vie Populaire, as well as a couple of other magazines and occasional book covers. Soon after, he got a chance to make illustrations for the biggest Art Nouveau publication – Art et Decoration; an experience that would strongly influence the direction of his own artistic expression.

The year 1894 was the breaking point for Mucha’s artistic career. He started working with famous Parisian theatre actress Sarah Bernhardt, who commissioned Mucha to illustrate the poster for her theatrical play Gismonda. Mucha’s work was the second version of the poster for the theatre play, realized to promote the extension of the play after the Christmas break. The poster depicted Bernhardt in the costume of a Byzantine noblewoman, dressed in an orchid headdress and floral stole holding a palm branch. The picture of the woman was human size, making the poster almost 2 meters high. A distinctive element of the poster was the lettering in the shape of an arch framing Sarah’s head. This style of lettering embodied the Art Nouveau elements and became a distinctive feature of Mucha’s style in posters and advertisements. The poster for Gismonda was presented on the streets of Paris on January 1, 1894, to the enjoyment of the public. Sarah Bernhardt commissioned Mucha to make posters for her plays for the six following years and Mucha started to gain big fame and recognition.

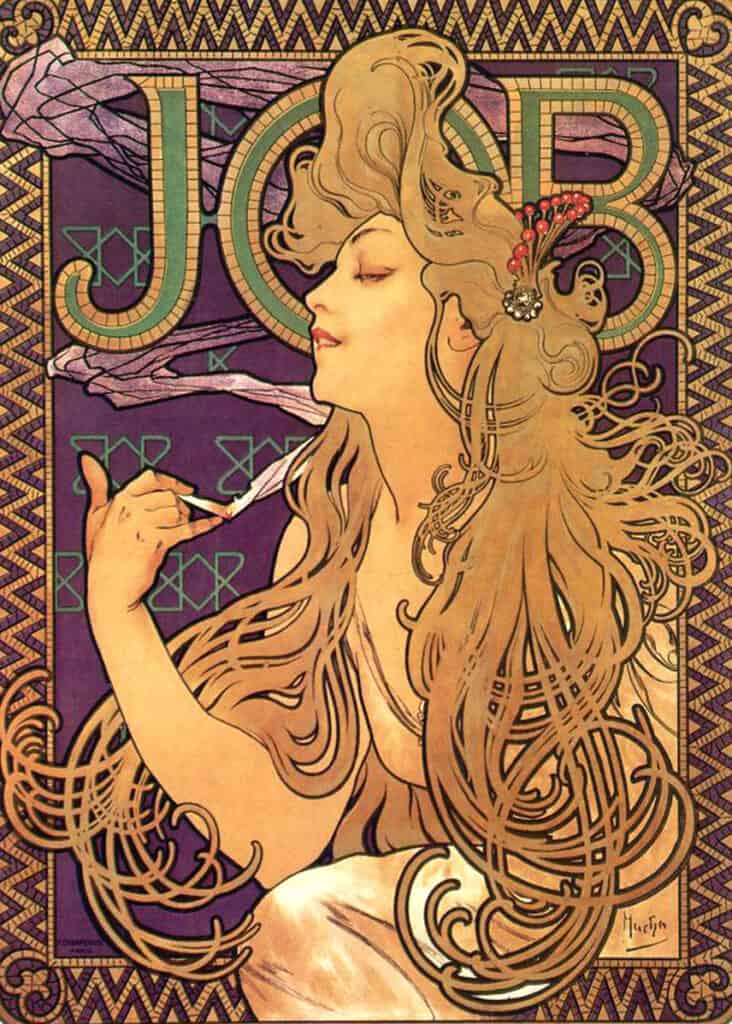

After his breakthrough in 1894, things got busy for Mucha. He started designing posters and advertising campaigns for big brands such as JOB cigarette papers, Ruinart Champagne, Nestlé, Idéal Chocolate, the Beers of the Meuse, Moët-Chandon champagne. He also created designs for posters with no commercial purposes that were sold individually for a modest price. His iconic posters mostly depicted images of women in floral settings, in the sinuous Art Nouveau style. Among his decorative poster designs, stand out The Seasons, The Times of Day, The Moon and the Stars, and his famous calendar depicting a woman’s head surrounded by the twelve zodiac signs.

Alphonse Mucha at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition

By the time of the infamous Paris Universal Exposition of 1900, Mucha was already a well-established artist all across Europe and got the opportunity to engage with large-scale paintings, taking a break from commercial drawings: the Austrian government commissioned him to create a series of historical murals to decorate the Pavilion of Bosnia and Herzegovina at the exposition. For this project, Alphonse Mucha received official recognition from both the French and the Austrian governments.

America and the beginning of The Slav Epic

Along with Sarah Bernhardt’s plays, Muchas’s posters toured the US, to the point that, when Mucha moved to New York in 1904, he was already a recognized artist. His purpose was to search for funding for a new, big project entitled ‘The Slav Epic‘, which Mucha had initiated during the 1900 Exposition. In New York, the artist rented a studio close to Central Park where he painted portraits and gave painting lessons.

Very soon after his arrival in the US, he connected to the Pan-Slavic organization and attended some of their events. There, he met Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy businessman and passionate Slavophile. Crane commissioned Mucha to make a portrait of his daughter in his recognizable artistic style and later Mucha used that portrait to create Slavia, the female character displayed on the bill for the 100 Czechoslovak Kroner. Crane became one of Mucha’s important patrons and the one who financed what would become the biggest project in Mucha’s career, The Slav Epic. After his American venture, Mucha decided to come back to Europe and focus his attention on depicting the history of the Slavic people. His first project was to decorate the Lord Mayor’s Hall in Prague’s Municipal House. As he aimed to depict the importance of Slav’s contribution to European history, the illustrations were reflecting power, national pride, and patriotism, resulting in an artistic style significantly different from his commercial work in Paris and New York.

The Slav Epic of Alphonse Mucha

Following the completion of the Lord Mayor’s Hall decoration, Mucha could finally focus on The Slav Epic, a monumental cycle celebrating the culture and history of Czechs and other Slavic peoples. He painted the cycle from 1912 till 1926 and the big reveal happened in 1928, on the 10th anniversary of the independence of the Czechoslovakian people. In preparation for this project, Mucha traveled to all the Slavic countries, making sketches and taking photographs of the people, aesthetics, behaviors, traditions, environment, and everything else needed to create the most accurate representation of the Slavic culture. The series consisted of twenty paintings: ten of them devoted to the history of the Czech people, and the rest to all the other Slavic nations. Canvases were six meters tall and eight meters wide.

Latest years

After finishing The Slav Epic, Mucha started working on The Three Ages, a triptych including The Age of Reason, The Age of Wisdom, and The Age of Love. He worked on the project for a couple of years, but he never completed it. In 1939, when German military forces entered countries of former Czechoslovakia, Mucha became one of the prime targets because of his strong Slavic patriotism. He got arrested, interrogated, and then finally released. Already in his late seventies, Mucha’s health was quite fragile, and soon after these events, he contracted pneumonia, dying on July 14, 1939, just a few weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Relevant sources to learn more

For other Art Nouveau artists, see:

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Aubrey Beardsley

Louis Comfort Tiffany

Gustav Klimt

Antoni Gaudí