Interviews

Land of Dreams – Interview with Shirin Neshat

Courtesy the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, Cape Town and London

By Shira Wolfe

“My work has always been very personal, but for some reason making work that touches on surrealism, magic realism and dreams is interesting, because on the one hand, the work is very specific to our culture, but on the other hand, because they do not use the logic of reality, the ideas can transcend specificities of a culture and time.”

Shirin Neshat

Shirin Neshat hovers between worlds with the presence and strength that belongs to those who have several homes and do not fully belong anywhere, therefore belonging everywhere. Since the 1990s, Neshat has created powerful works of art dealing with the political and societal changes in Iran, the position of women there, and her experience as an Iranian woman living in exile in the United States. When she first returned to Iran after 12 years living abroad, the visit sparked a strong impulse to return to creating art. In her early works Unveiling (1993) and Women of Allah (1993-1997), she presented self-portraits and portraits of other women, combining several contrasting symbols: the chador, the gun, the Farsi text, and the strong gaze of the subject. Written on the exposed skin of her subjects (their hands, feet, and faces) are poems in Farsi.

Neshat’s most recent body of work, Land of Dreams (2019-2021), turns for the first time to the people of the United States, her home country since she left Iran at the age of 17. The body of work comprises a series of portrait photographs, a two-channel video installation, and a feature film. In the videos and film, we follow Simin, Neshat’s alter ego, as she photographs Americans in their homes and asks them to share their last dream with her. As the plot develops, we learn that Simin is working for a government agency where they interpret people’s dreams to better understand and control the population. In the video installation, Simin works for an Iranian agency, while in the feature film she works for the Americans. In making these choices, Neshat deliberately plays with the long-time political animosity between Iran and the United States.

In concurrence with her current exhibition Shirin Neshat: Land of Dreams at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto (March 10 – July 31, 2022), we spoke with Shirin Neshat about her body of work Land of Dreams, about the transition from creating works mainly about Iran to creating works that are about the United States, and about the excitement of embarking on new projects.

Shira Wolfe: I wanted to ask you about Land of Dreams and your approach to working with dreams. Dreams are so intimate, you’re going into someone’s subconscious. Was there an element of the history of dream interpretation present as inspiration for this project?

Shirin Neshat: My idea for doing this project wasn’t really rooted in the history of interpretation of dreams, the Jungian or Freudian or anything like that. It was more philosophical in terms of what my dreams meant to me and what they signified when I repeatedly saw things that bothered me during the day, things I tried to avoid, which sometimes visited me at night. As opposed to people who are really working in dream analysis and spending their lives talking about the meaning of dreams, my project is far more conceptual.

I made three videos before called Dreamers (2013-2016), and they were essentially three videos about my dreams. And I thought it would be very interesting now to make a new project that was not about my dreams but about collective dreams of other people. But I was also playing with the idea of a more politically charged work, America being “the land of dreams”, and if dreams are meant to be a projection of people’s dreams and anxieties, what are Americans dreaming about? A lot of the dreams in the video were scripted, inspired by dreams that we had heard. So I wasn’t literally collecting people’s dreams, but created a project that put a focus on people’s subconscious. What are people dreaming about, especially at this point in the history of America?

Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York, and Brussels

SW – And how did you develop your own dreams into the Dreamers videos? Was it very different compared to working with other people’s dreams?

SN – Yes, you know, I dream a lot, and I always write down the dreams that are interesting and I began to see certain patterns in my dreams. For example, in my most important dreams, my mother always appeared, who lives in Iran and I live in the US. And she always appeared as this savior, this person who is this unconditional love in the worst moments of crisis. And then I realized when I made those dreams into videos, that she represented more than just a mother, but also the motherland. The nostalgia for home, for the motherland. And the fact that my mother was aging and she might die could mean that I might lose my connection to the motherland. So a lot of it was my own interpretation, but I felt that clearly that was my anxiety: that the loss of my mother would mean the loss of my connection to Iran, since I live in exile.

SW – It’s beautiful that you are placing these dreams almost as characters in your work. Many people don’t take this part of ourselves, the subconscious, seriously. And as you said, this is a place where personal experiences and truths emerge, you cannot avoid them, and you’re piecing things together in another way. I appreciate that very much about your work, that you are using the subconscious as a tool to help us understand.

SN – My work has always been very personal, but for some reason making work that touches on surrealism, magic realism and dreams is interesting, because on the one hand, the work is very specific to our culture, but on the other hand, because they do not use the logic of reality, the ideas can transcend specificities of a culture and time. And people cannot reduce it to simply being about Iran, but it transcends all that and becomes more about the subconscious.

As someone who started with making works like Women of Allah that are very politically charged and more direct, I slowly drifted towards works that are much more evocative, even though they are political. They really try to appeal to the audience on a more emotional, and I would say subliminal level.

Copyright Shirin Neshat. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York, and Brussels

SW – With Women of Allah and Unveiling, you included poetry with the photography, so in that sense you had that symbolic layer there as well.

SN – Yes. The work was still very conceptual, but for example Women of Allah with the weapons, it talked about martyrdom and revolution and the whole fanaticism of the government, and these were real issues, so the poetry or the artistic nature of the work was undermined. And I think what people ended up doing both in the West and in the East was to rush towards a judgment, like that this is telling you revolutions are good, or that these women are submissive, or the government is bad… There were all these conflicting interpretations and I didn’t think they were right, but because it was so directly political, most people couldn’t pay attention to the symbolism and the poetry, and just got involved with the image.

SW – And the poets that you were quoting in these pieces were Forough Forrokzhad and Tahereh Saffarzadeh?

SN – Yes, Forough Forrokzhad is included in the ones without the gun, because she died before the revolution. Her poetry is really timeless and worked very well with the images. But Tahereh Saffarzadeh is different because she wrote with a very strong conviction to the revolution. So those are very revolutionary poems, and in fact they were very provocative. The things that she said maybe made people think even more that I am calling for violence. Because she was writing to the men: “I want to also hold arms and join you, and help you with the revolution.” And that’s pretty strong stuff. But I thought it was really relevant to the images of the women holding arms.

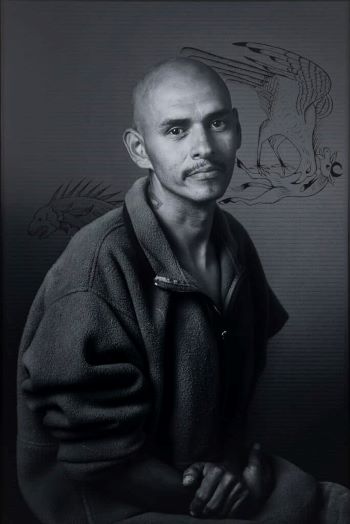

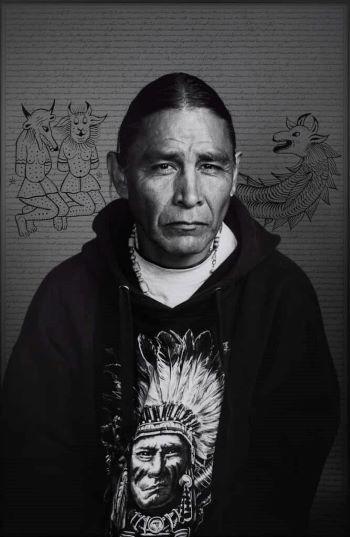

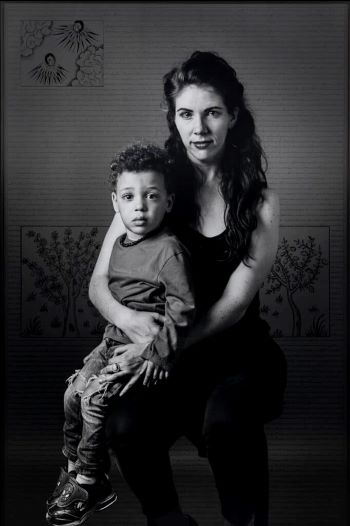

Left: Shirin Neshat, Alfonso Garundo, from Land of Dreams series, 2019, Digital C-Print with ink and acrylic paint

Right: Shirin Neshat, Raven Brewer-Beltz from Land of Dreams series, 2019, Digital c-print with ink and acrylic paint

Copyright Shirin Neshat. Courtesy the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, Cape Town and London

SW – And in Land of Dreams you used writing as well, but this time it’s the dreams, and there is no writing on the faces but the writing is behind the subjects.

SN – This was the first time we had Western subjects, and I’ve only ever applied Persian calligraphy on the faces of Iranian and Middle Eastern people. It was a really interesting challenge to incorporate this Persian Farsi text into the background of Native Americans, African Americans, Whites, Mexicans. It was a really good breakthrough.

The writings in the background are from a very ancient book from the 11th century called Creatures of Wonders. It’s never been translated, but we photographed the original copy at the library in Iran. That book more or less describes dreams, and the illustrations are of creatures that are not worldly, like half fish-half cow… Only things that exist in dreams. The writing also talks about different categories of dreams. So I was taking these contemporary Americans’ portraits and applying this very ancient Iranian book to them. To me, that was more of an interest than anything else.

SW – It’s very interesting that this is the first time that you do a project in this sense in the States, where you lived for so long. Your works before were mostly related to Iran or inspired by Iran, and now you are working with people who are from the States. Do you think this is something you will continue with for future projects, now that you have kind of broken into this in-between place?

SN – Exactly. I mean, there were times when people were asking me if I would consider making a film about America. And that was hard for me to imagine, going from engaging with an Iranian or Middle Eastern subject to an American culture completely. But what has happened now is that the new work is still from my point of view as an Iranian, and the main character is an Iranian, but it is not about Iran, it is about America. And this may stay like this for a while before I can transition completely where I can take the Iranian out. Because I am as American as Iranian, I know this country really well, and I have many stories to tell that are from this end. I feel like it was also time to close that chapter of pure nostalgia, memory, and questioning about a country that I can never visit… And now I feel like a new door has opened where I can explore topics that could be about other cultures, but always from the point of view of an Iranian, which is me.

SW – Exactly. For example, you wrote that your work Passage was inspired by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on one level. On another level, it was also of course you, and coming from Iran, and this background. And that was very powerful for me when I saw those images, knowing Palestine and Israel well, and to see that your work is always coming from your experiences but it also connects to those other topics and places.

SN – Thank you for saying that. It’s always a challenge for me because the tendency of the audience is to reduce you to a certain thing and then you yourself get very accustomed to making that kind of work or that kind of theme. But to break out of your own mold and to break out of the boundary you have created for yourself takes a lot of courage. And to be honest, I was very nervous about making a work about America. It could have been very problematic. But now that I’ve done it, I feel like I gained confidence and will find my way in balancing things. I’m just following my intuition.

“I’ve always done a lot of work about women in a state of madness, where ultimately they find a kind of freedom in this state of madness.”

Shirin Neshat

Courtesy the artist, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, and Galerie Jérôme de Noirmont, Paris

SW – And in terms of the medium, you continue with photography and film, mostly? I’m very curious if you work with some other mediums as well, but perhaps use them more for your personal practice and don’t show this to the public?

SN – I’m still doing photography, video, and dreaming about a new movie. The thing is, nothing I do is very spontaneous. When we do photography we plan for it, we make mood books, we prepare months if not a year in advance. Then we set up the studio and we photograph people, and we have to figure out the writing. But I am directing an opera, Aïda, which is kind of new for me. I did one in 2017, and a revised version of it comes in August.

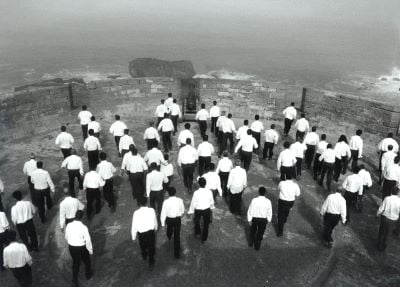

I’ve also been studying African dance ever since I know myself, so that’s something that I keep very private, but I have a love-affair with choreography and dance. Choreography in terms of the body as your instrument. So there’s a lot of choreography in many of my films and video’s. For the opera, I am working very closely with the choreographer to decide on the style of the dance, making it much more ritualistic as opposed to like modern dance.

SW – Connecting to this, I’m curious how the process of collaboration is for you. You’re working a lot with other people when you’re doing your movies and photography, yet as I feel from your work it is very specific what you need to say and how you need to do things, and collaboration can be a lot of giving and taking, silence and action…

SN – Right this moment we are working on a new video, so the team is back together, I deliver them ideas, and of course everybody comes with their own suggestions and input. I find the greatest challenge for me is to listen to them and take the best ideas, and then reject the ones that I don’t like and be very strict, and not just nice about it. It’s a real process, but I’m very blessed because I’m working with the same people I’ve been working with for a long time, and they’re my closest advisors because they know me really well, they know my strengths and weaknesses. But my greatest challenge, again, is to be that leader in terms of making sure I don’t compromise and change the idea just to be nice.

SW – And do you also need to retreat sometimes?

SN – Oh yes. The idea that I’m working on now, I didn’t talk about that with anyone for the first four months. I think it was after five months, I said only a few words to my husband, who is my closest collaborator, just to test out if I was absolutely nuts. And when I got his positive reaction, I mentioned it to the cinematographer who is the next closest consultant. Sometimes it’s like having a child. You need to not tell everybody yet, until you feel like it’s grown up enough that it’s pretty safe. I think one bad reaction could end your enthusiasm.

SW – Could you share anything more about this project?

SN – It actually came from the previous video, Land of Dreams, which is about an Iranian woman living in America. In this case she is someone with a very traumatic past, and even though she is free in America and can do whatever she wants, mentally she is still trapped in some terrible things that happened to her in the past; it’s political, it has to do with sexual assault… But what really helps her is dance and music. And she intensely, obsessively dances and listens to music in her room, but then anytime she goes outside, it’s like she’s walking on the moon, like she can’t relate to America, to the people, and it’s just a strange world because she lives in her own head.

So it’s a little bit about mental illness and madness. I’ve always done a lot of work about women in a state of madness, where ultimately they find a kind of freedom in this state of madness. For example in Possessed, or Women Without Men… I’m very interested in people who live on that edge of sanity and insanity. Like artists!

SW – I read somewhere that you were talking about repetition, and how repetition becomes this methodology for you to deal with daily pressures. That was inspiring for me, and I was wondering what kind of repetition and what kinds of routines you are incorporating in your daily life?

SN – Thank you for asking, because I was just away for three weeks, and I was away from my repetitions and patterns and felt so disoriented. And the last few days I’ve started again. Every day, first thing, I walk with my dog for a good hour, and call my mom or listen to music or run. And four nights a week I take dance classes, and they really charge my batteries. Because I have the tendency to be like a machine, and I only really stop when I’m dancing or walking my dog and listening to something, then I’m not thinking. The less I think the more I’m able to decompress, and then I’m really happy. My repetition of patterns really helps me, because my days are very challenging. I mean, it’s just art, it’s not like science, and I always have to tell myself: “Enjoy what you’re doing, because in the end, what does it matter?”

SW – Absolutely, but then if you don’t do it, no one is going to do it.

SN – Oh yes, and I do it because it makes me happy. But the minute you get stressed and angry, it’s like, what is this about? Then you have to just enjoy the process and remember why you’re doing it. And then you feel better.

SW – So what are your creative needs at the moment?

SN – I always feel like beginning something new. I like new beginnings. I don’t like it when I feel like I’m sitting here, going back to promoting my old work. At this moment I’m very excited because we’re making something new, I’m excited about the opera. So I think what really keeps me going is when my imagination is active.

Copyright Shirin Neshat. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York, and Brussels

SW – How was it for you to set up this exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto? Because you chose very clearly which pieces you wanted to show, and it was very much centered around Land of Dreams.

SN – Yes, I worked very well with the really wonderful artistic director and curator November Paynter. And there is a large Iranian community in Toronto that I care a lot about, and a wonderful art community. So Toronto as a city is very important to me and I didn’t take it lightly. We worked together to choose an exhibition that is not overwhelming and is very focused on some of the latest work and some of the earliest work.

SW – Shirin, it was really lovely to meet you, thank you for taking the time to talk.

SN – It was lovely talking to you! Have a wonderful evening.

Shirin Neshat: Land of Dreams is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto through July 31, 2022.

Relevant sources to learn more

Discover works by Shirin Neshat for sale on Artland

Read more on Shirin Neshat

National Museum of Women in the Arts

Pinakothek der Moderne

Read other artist interviews in the Artland magazine

Jwan Yosef

Inma Femenia

Kojo Marfo

Wondering where to start?