Articles and Features

Artists In Residence:

The Studios Of Modern Sculptors

Courtesy Bowness. Barbara Hepworth © Bowness.

By Adam Hencz

Our Artists In Residence series is dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists’ workspaces, in the company of their creatively striking residents. We offer a glimpse of the innermost environments some of the greatest modern and contemporary artists lived and created in. The series unveils everything from the intimacy of urban ateliers, through the pleasant creative mess of remote spaces, and hints at the personal lives of the individuals beyond their well-known artistic production. The first edition of our series explored the studios of Abstract Expressionist painters of the ‘50s and ‘60s in New York City and its vicinity. This week, we sojourn at the creative spaces of two pioneering modernist sculptors; at the secluded St Ives studios of Barbara Hepworth and the eccentric Paris atelier of Alberto Giacometti.

Barbara Hepworth

A leading figure of modern British art in the mid-20th century, Barbara Hepworth established innovative techniques and pushed the boundaries of traditional sculpture. She developed a unique avant-garde method to form sculptures, working directly into the chosen material. In the 1920s at the Royal College of Art in London, Hepworth and fellow student Henry Moore went against the more traditional process of making preparatory models and maquettes and carved directly into stone. Her works were well received and were among the earliest abstract sculptures produced in England. By traveling across the continent and visiting the studios of some of Europe’s most influential artists, she met Picasso and Brancusi and herself became a key figure of an international network of abstract artists.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Hepworth and her husband, painter Ben Nicholson moved to St Ives in Cornwall with their family. Hepworth began experimenting with ways to open up sculptural forms, developing a new language with hollowed out forms from small logs of wood, using color and strings to emphasize the negative space. Her sculptures reflect her fascination by our relationship to the natural world, her experience of nature and the landscape around St Ives. Her art brings the nuances and richness of materials, primarily wood, stone and bronze. She stayed and worked in St Ives for the rest of her life. Living in cramped conditions and having little time to work, Hepworth was unable to make major works during her first years in St Ives. However, by the end of the 1940s her practice evolved into having major commissions and creating a body of work to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1950.

Hepworth was in need for a larger, airy and serene studio space. Upon the recommendation of a close friend, she purchased a twin summerhouse up on the hill in Trewyn in 1949. With its outhouses and gardens, the Trewyn home gave her the freedom, the space and the light she needed to develop larger-scale works. The building and its surroundings had a huge impact on Hepworth’s works, providing various environments to the artist to formulate her pieces. The courtyard, “the garden protected by tall trees”, the first-floor studio, the stone-carving workshop, and the plaster workshop all had their mark on the conceptions of scale and of space.

Courtesy Bowness. Barbara Hepworth © Bowness.

In the late 1950s she began working with bronze that allowed her to create more robust pieces to the public commissions she was receiving. In 1961, she acquired the Palais de Danse studio across the road from Trewyn, where many of her larger plasters such as Single Form were made. In accordance with the artist’s wishes, the Trewyn studio and garden was turned into a museum after her death. The museum now contains the largest permanent survey of Hepworth’s works, and has been owned and run by Tate since 1980.

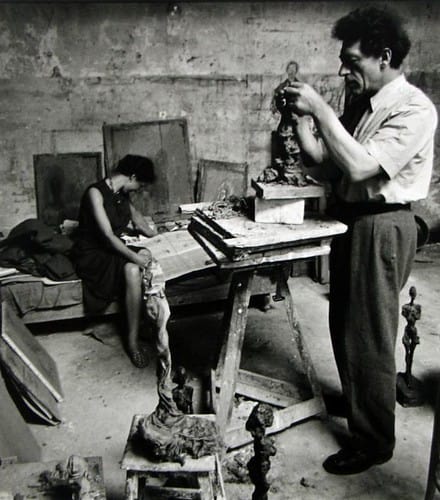

Alberto and Anette Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti’s studio is inseparable from the artist’s legend and is necessary for an understanding of his work. The atelier has become the symbol of post-war artistic life of Paris’ Montparnasse neighborhood, immortalized by photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, René Burri or Ernst Scheidegger. In the winter of 1926, the Swiss sculptor and painter moved to his studio at Rue Hippolyte-Maindron. He would spend the next forty years within the confines of this space and creating spindly sculptures and haunted portraits. With an area of only twenty-three square meters, a high ceiling, dim lighting and no running water, the Parisian studio was extremely simple and bare. Even after his economic success, Giacometti would not transform or leave the space that over the years, came into an almost mythical status. It offered the right environment for Giacometti to pursue the cycles of creation and destruction, a central phenomenon to his existence as he would carefully examine and tirelessly question his work. These ideas of decay and impermanence were manifested in the crumbling flesh of his bronze figures.

Giacometti is widely acknowledged for having made some of the most important contributions to Surrealist sculpture in the 1930s, sculpting on the human head, focusing on the sitter’s gaze. During the Second World War, Giacometti searched for refuge in Switzerland where he met Annette Arm, a secretary for the Red Cross. The two married in 1949 and for the rest of Giacometti’s life, Annette remained his main female model. After the war, the sculptor returned to his studio, and his small-scale pieces grew larger in size but became thinner as he started creating his haunting figurative sculptures. He stayed hugely influential in the art scene and until the very end of his artistic career was riding a wave of international popularity. When Giacometti died in 1966 without a will, his widow Annette salvaged the entire contents of the studio. In 2018 the Giacometti Institute in Paris finished the recreation of the Swiss sculptor’s intimate studio and is home to a faithful reimagining of the artist’s chaotic atelier.

Relevant sources to learn more

Barbara Hepworth Estate

The Giacometti Foundation

More from the Artists In Residence series

Artists In Residence: The Studios of The Abstract Expressionists

Incredible Artist Homes series

Incredible Artist Homes: Part I. The Nineteenth Century Grandees

Incredible Artist Homes: Part II. The Modern Pioneers