Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Magdalena Abakanowicz

By Shira Wolfe

“I am interested in every tangle of thread and rope and every possibility of transformation. I am interested in the path of a single thread. I am not interested in the practical usefulness of my work.”

Magdalena Abakanowicz

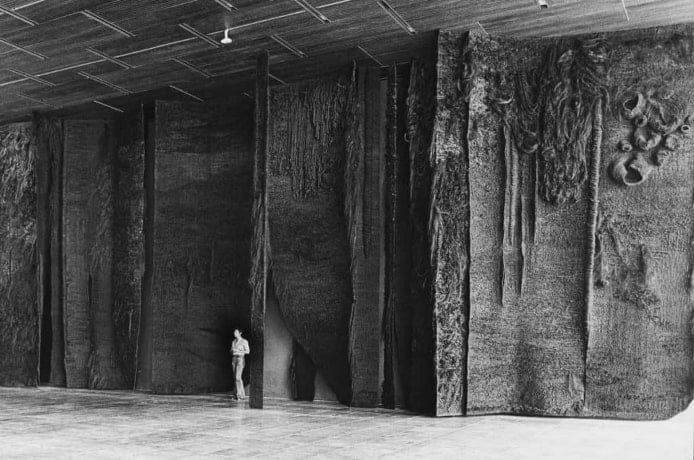

In this edition of “Female Iconoclasts”, we celebrate the art of Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), Polish pioneer of woven art and leader of the New Tapestry movement in late 1960s Europe. She became known in the 1960s and 1970s for her large woven sculptures, named Abakans after her surname. Moving from two-dimensional to three-dimensional fiber art, these Abakans challenged the very notion of what people thought of as sculpture and opened up new forms of art installation. Later in her career, Abakanowicz developed awe-inspiring sculptural works in the public sphere, often interacting with nature. A current retrospective at Tate Modern allows for a fascinating, richly sensory experience of Abakanowicz’s majestic woven works.

Jana Kosmowskiego, Warsaw

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Beginnings

Magdalena Abakanowicz was born in 1930 into an aristocratic family – her father was of Russian and Tatar descent, and her mother came from Polish nobility. She grew up in Falenty, near Warsaw, but after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939, the family moved to their estate in the forest, 140 km from Warsaw. After the war, Abakanowicz studied at the secondary school for plastic arts in Gdynia between 1948-49, and she came into contact with weaving during her time at the fine arts school in Sopot between 1949-50. When this program was canceled, she continued at the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw, where she graduated in 1954 having specialized in weaving. In order to support herself so she could create her art, Abakanowicz worked in industry and also took part in design exhibitions organized by the state. Her first solo exhibition was held at the Ministry of Art and Culture’s Galeria Kordegarda in Warsaw in 1960. However, before it opened to the general public, the show was closed by authorities since they found the exhibition too formalistic and not engaged enough with socialism. The strict rules that had loosened up a bit after Stalin’s death were returning with strong consequences.

“The Abakans were a kind of bridge between me and the outside world. I could surround myself with them; I could create an atmosphere in which I somehow felt safe because they were my world; they were something between figurative and natural, like animals, like figures, while abstract, like geometric forms, but never to be definitively described.“

Magdalena Abakanowicz

Defining Her Artistic Language – The Abakans

During the 1960s and 1970s, Abakanowicz came more and more into her own, forming her very own distinct artistic language. Defying categories like tapestry, textile, decorative art or fine art, she began creating large three-dimensional woven works, which became known as the Abakans. She described them as a bridge between herself and the outside world, an atmosphere in which she could feel safe, both figurative and natural. Abakanowicz always thought out of the box – in her earliest weavings, she was already improvising without following any design and was working towards sculptural woven artworks. In 1967, she created her first totally three-dimensional sculptural forms. She would place these Abakans together in installation compositions, which she would call “situations”.

In 1970, she collaborated with film directors Jaroslaw Brzozowski and Kazimierz Mucha to make the film Abakany, a surreal film featuring her Abakans, set on the sand dunes of Słowiński National Park along Poland’s Baltic coast. In the movie, Abakanowicz and others move among her large, mysterious sculptural tapestries.

Magdalena Abakanowicz’s Situations and Travels

Over time, Abakanowicz increasingly developed the idea that her artworks were environments in space. She began working on large-scale Situations often using rope to connect her different works. The year 1970 marked her first major public commission in the Netherlands, which she named Bois le Duc, inspired by the area in which she was working around the city Den Bosch (The Forest). For the commission, she created a large tapestry work for the provincial government building. It emerges like a dark, earthy, primeval forest. Throughout the 1970s, Abakanowicz traveled a great deal, participating in 21 solo exhibitions and 75 group exhibitions. This traveling was extremely important to her, as she felt compelled to communicate from Poland to the rest of the world, manifesting her country’s contributions to the art scene.

Reflecting on the Violence of Humans

From the 1980s onwards, Abakanowicz became deeply engaged with nature and humans’ potential for violence towards each other and the natural world. Between 1987 and 1995, she found felled trees in the Masurian Lake District in Poland, and created 21 large forms from the old trees, attaching cloth and other materials to them. She then placed these on metal bases, creating a suggestion of weapons, artillery vehicles, and bodies. In 1993, Abakanowicz created a permanent monument to the victims of the nuclear bombing in Hiroshima, in the shape of 40 seated bronze human backs, named Space of Becalmed Beings, an artwork that held great personal significance to the artist. These figures were installed permanently on the terrace of the Contemporary Art Museum of the City of Hiroshima, situated on a mount overlooking the city, where it is said that people would seek shelter in the aftermath of the atomic bomb, and many died there. The sound of the air through the figures seems to reverberate the cries of those who died there, and sometimes it can be heard repeatedly when the museum elevators stall between floors for no apparent reason.

Other Notable Public Works

Abakanowicz’s other notable public works include Katarsis, 33 standing bronze figures for the Spazi d’Arte sculpture park in Italy; Negev, heavy limestone wheels responding to the desert environment in the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden in Jerusalem; and Agora, her largest and last public project consisting of 106 tall headless figures cast in iron, standing in Chicago’s Grant Park. The work symbolizes the shared need for mutual support and comfort, especially in this particular historical moment. In fact, all of Abakanowicz’s works, particularly the Abakans, resonate with this theme. They are forms that speak back to the viewer, to admire in awe and get very close to in a deeply intimate manner.

Magdalena Abakanowicz – Every Tangle of Thread and Rope, runs through 21 May 2023 at Tate Modern in London.

Relevant sources to learn more

Controversial Public Art. Debate, Fury, Vandalism and Loss

Installation Art: Top 10 Artists Who Pushed the Genre to its Limit

The Fibers and Fabrics of Textile Art. How Classic Craft Found Its Way Into Fine Art Practices

For previous editions of our Female Iconoclasts series, see:

Marina Abramović

Niki de Saint Phalle

Georgia O’Keeffe

Graciela Iturbide

Louise Bourgeois