Articles and Features

The Aesthetic Of The Banal In Contemporary Art

“There is an aesthetic of familiarity, a sedative of ordinariness which dulls the senses and hides the wonder of existence”.

Richard Dawkins

It is not uncommon, while visiting contemporary art museums, to hear someone whispering: “Is this art? I could do that!” – we might even have said it ourselves!

Much has been said by experts and art historians in this regard, and why this statement generally proves to be false: we would not actually be able to do said art – and even if we would, still we did not think of doing it. To explore the reality behind this long-standing discussion would necessitate a much longer investigation, but yet we may ask ourselves why, inevitably, do we tend to perceive some of the finest examples of contemporary art as something so close to our experience of the world that we might have thought of creating ourselves.

This tendency derives partly from the abandon of traditional artistic techniques, partly from the intentional introduction of the mundane – images as well as objects of commonplace existence – in the art practice.

Looking back on the origins of contemporary art, it was arguably Marcel Duchamp the artist who first caused a similar reaction when, in 1917 in New York, he submitted a standard urinal for an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. Fountain would become one of his most notorious works as well as one of the first steps towards conceptual art. In a 1964 interview with Otto Hahn, Duchamp suggested he purposefully selected a urinal because it was disagreeable. The choice of a urinal, according to the artist, “sprang from the idea of making an experiment concerned with taste: choose the object which has the least chance of being liked. A urinal—very few people think there is anything wonderful about a urinal”.

Duchamp’s groundbreaking act would open the floodgates to the aesthetic of the banal in art, revealing to the world that beauty and meaning can exist in the strangest of places and objects.

“It is neither Art for Art, nor Art against Art. I am for Art, but for Art that has nothing to do with Art. Art has everything to do with life, but it has nothing to do with Art”.

Robert Rauschenberg

Banality as a Creative Strategy: Pop Art

Around forty years later, in the vibrant context of New York’s intellectual life, a couple of artists bucked the dominant trend, Abstract Expressionism, and the idea – typical of the movement – that artworks are the individual expressions of an artist’s genius by reintroducing fragments of reality into art through images and combinations of everyday objects. They were Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

With his Combines, artistic creations in the intersection between painting and sculpture, Rauschenberg explored the blurry boundaries between art and the everyday world literally incorporating commonplace objects into painted canvas surfaces.

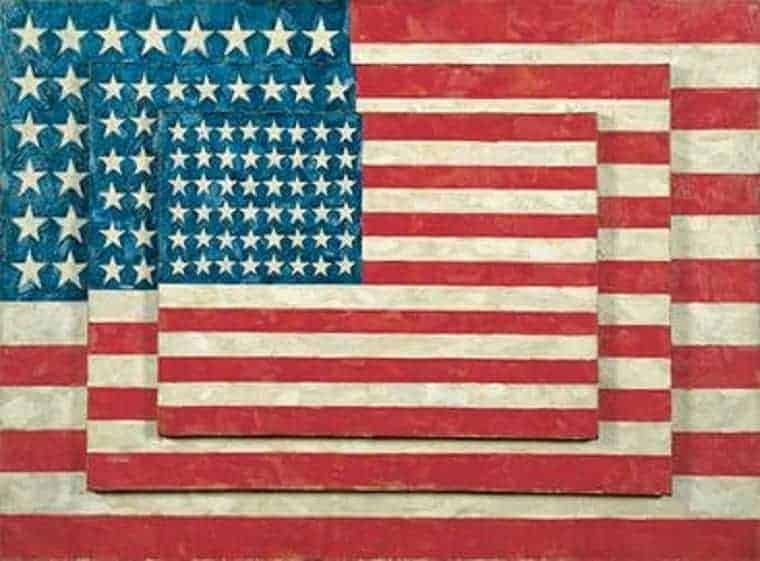

Johns, for his part, working in a variety of media, represented what he defined as “things the mind already knows”, a selection of recurring concepts and imagery: targets, maps, letters, but also numerals and flags – a plethora of signs and symbols that he turned into abstractions.

He wanted to shift the visual emphasis of familiar symbols from their meaning to their aesthetic qualities. In relation to his famous depictions of the American flag, he once explained: “To me, the flag turned out to be something I had never observed before. I knew it was a flag and had used the word flag; yet I had never consciously seen it. I became interested in contemplating objects I had never before taken a really good look at. In my mind that is the significance of these objects”.

But the artist who really captured the power of the ordinary and made of the aesthetic of the banal his signature style was undoubtedly Andy Warhol.

Heavily influenced by his commercial art practice, Warhol decided to create something that was immediately recognisable. In the America of mass consumption, what could be more popular than products inundating the shelves of departmental stores and iconic celebrities?

The screen-printing technique allowed him to produce striking, boldly coloured images as repeated patterns, finding in flatness and multiplicity a reflection of the mass-production culture, while simultaneously subverting the idea of painting as a medium of invention and originality.

“I was involved with banal images. I realised that people respond to banal things; they don’t accept their own history; not participating in acceptance within their own being”.

Jeff Koons

The Aesthetic of the Banal: Recent Developments

More recently, different artists have declined the theme of banality in its various aspects.

Some have highlighted the kitsch and grotesque side of the familiar, some others – Duane Hanson stands out among the others – have employed the compelling aesthetic of the banal as an ironic commentary on today’s consumer society.

To the first group belongs instead American artist Jeff Koons, whose best-known work is titled, in fact, Banality.

The series, from 1988, is a celebration of popular culture and includes a selection of ornaments one might find in a gift shop, from a sculpture of Michael Jackson with his pet chimpanzee to one of Saint John the Baptist. Their shapes and materials – ceramics, porcelain and painted wood – are carefully designed to appeal to middle-class tastes and their size is enlarged out of all proportion. Monumentality represents to Koons what repetition meant to Warhol: a creative strategy to de-familiarise everyday objects.

Intended to be accessible, Koons’ art is purposely meaningless, there is no right or wrong interpretation.

One hundred years after Duchamp’s Fountain, whether celebrated or questioned, banality and the aesthetic of the familiar still play a significant role in the contemporary artistic practice and encourage the audience to reconsider the power of the ordinary both in everyday life and in art.

Relevant sources to learn more

The Guardian – Interview with Jeff Koons

Portraits of America: Jasper Johns’ Three Flags