Articles and Features

Bill Brandt: The Beautiful and the Sinister

By Shira Wolfe

“I think a good portrait ought to tell something about a subject’s past and suggest something about their future.”

Bill Brandt

A recent exhibition at the FOAM in Amsterdam featured the sinister and Surrealist photographs of British photographer Bill Brandt (1904-1983). Brandt actually grew up in Germany, the son of a German-born father and a British mother. In 1927 he moved to Vienna, then to Paris, and finally, London, leaving behind his German roots and often concealing this information due to the rising anti-German sentiments in the 1930s, a result of the rise of nazism. Since his early photographs and throughout his later work, Brandt showed a fascination with the “unheimlich”, or the sinister, earning him the status as one of Britain’s most acclaimed photographers.

Want to learn more about Surrealism? Check out our overview of the movement.

Bill Brandt’s Sinister Surrealism

If it were not for the fact that he contracted tuberculosis at the age of 16, Bill Brandt may not have come to his fascination with the subconscious and Surrealism. After years of treatment in Germany, Brandt was sent to Vienna to complete his treatment for TB in 1927, and part of the treatment included consultations with a psychoanalyst. During these treatments, he became aware of the importance of the subconscious, while his life in Vienna simultaneously led him to meet the poet Ezra Pound, who, in turn, introduced Brandt to the photographer Man Ray in Paris. In 1929, Brandt moved to Paris and started his career as a photographer. Working in Man Ray’s studio for several months, he found himself at the epicenter of Surrealist art and photography. He learned various technical processes from Man Ray, such as the use of extreme grain and cropping for graphic effects, but also the heavy editing process in the darkroom that Brandt would come to use and the idea that the photographer should have the freedom to use any means to achieve his desired result were all creative approaches indebted to Man Ray.

Documentary Photography

Brandt was attracted to poetic approaches and the documentary, “moment of truth” approaches in photography that he discovered during his time in Paris. After Paris, he traveled to Hungary and Spain, and in 1931 he settled in London. There, he focused on documentary photography for the next 10 years. Yet in his documentary photography, Brandt always explored the sinister, the uncanny, and the hidden layers of our subconscious worlds.

The English at Home

Brandt’s first major book of photography, The English at Home, was published in 1936. Brandt intended to explore the deeply embedded social contrasts in Britain, even more drastic due to the economic crisis following the stock market crash of 1929. He was fascinated by secrets, facades, and the masks people wear. He would explore these contrasts in photographs of children sleeping, dreaming, or reading, while the adults are occupied in everyday life affairs. The concept of this publication was to make use of double-page spreads to juxtapose two images showing the opposing social classes, for example by depicting a maid preparing a bath while in the other photograph a young lady is shown, all dressed up for her evening out, stepping into a car.

A Night in London

In his second book, A Night in London (1938), Brandt was inspired by Brassaï’s Paris de Nuit from 1936. These photographs were all about capturing the melancholy and the sexual, as he was fascinated with ideas and stories of lovers, dreamers, and solitary characters. Unfazed by notions of strict authenticity, Brandt often used his friends and family to act as these characters, therefore allowing himself the creative freedom to show those London scenes that he had certainly witnessed, though perhaps not at the time of taking the photograph. His brother Rolf was one of his favorite models.

Institutional Commissions

When the Second World War broke out, Brandt started working for the British Ministry of Information. He was instructed to photograph Londoners sleeping in the underground stations, which they used as bomb shelters. Above ground, he photographed buildings in London in order to keep their images for posterity, in case they were wiped out by German air raids. These became haunting nocturnal images of a moonlit, abandoned, blacked-out London.

Portraits

After the war, Brandt stopped doing documentary photography, having lost his interest due to the increasing number of photographers working with this approach. In 1943, he started to devote his attention to portraiture, something he had started trying out at the beginning of the war, interested in capturing a suspended moment, not just appearances.

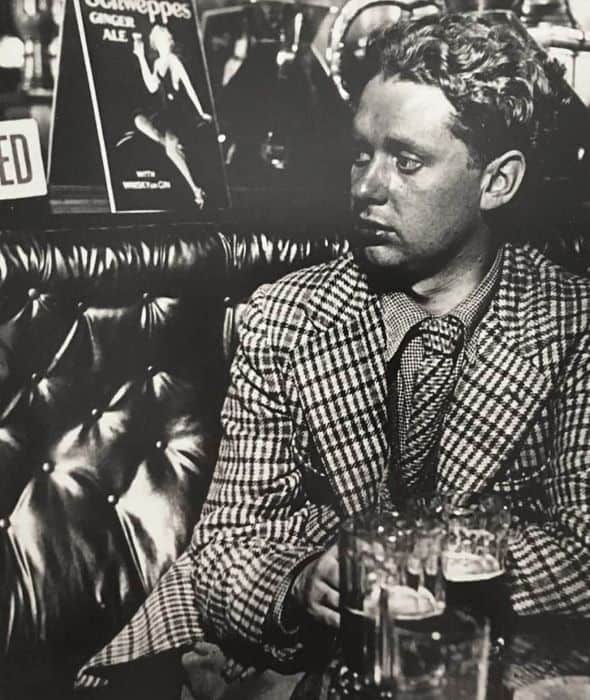

Young Poets of Democracy

Using a wide-angle lens for his portraits, he created a sense of distorted space. Many of his sitters were artistic types. His first portraiture series was called Young Poets of Democracy (published in Lilliput magazine in 1941) and included portraits of some of the leading poets of the Auden generation. Brandt was known to take his time setting up his portrait scenes until his sitters became either indifferent or impatient. As a result, he often created at the first sight impersonal portraits, in which an expression of personality was denied. The well-known artists sitting for Brandt would end up with secretive portraits, revealing a hidden mystery and depth that became his trademark.

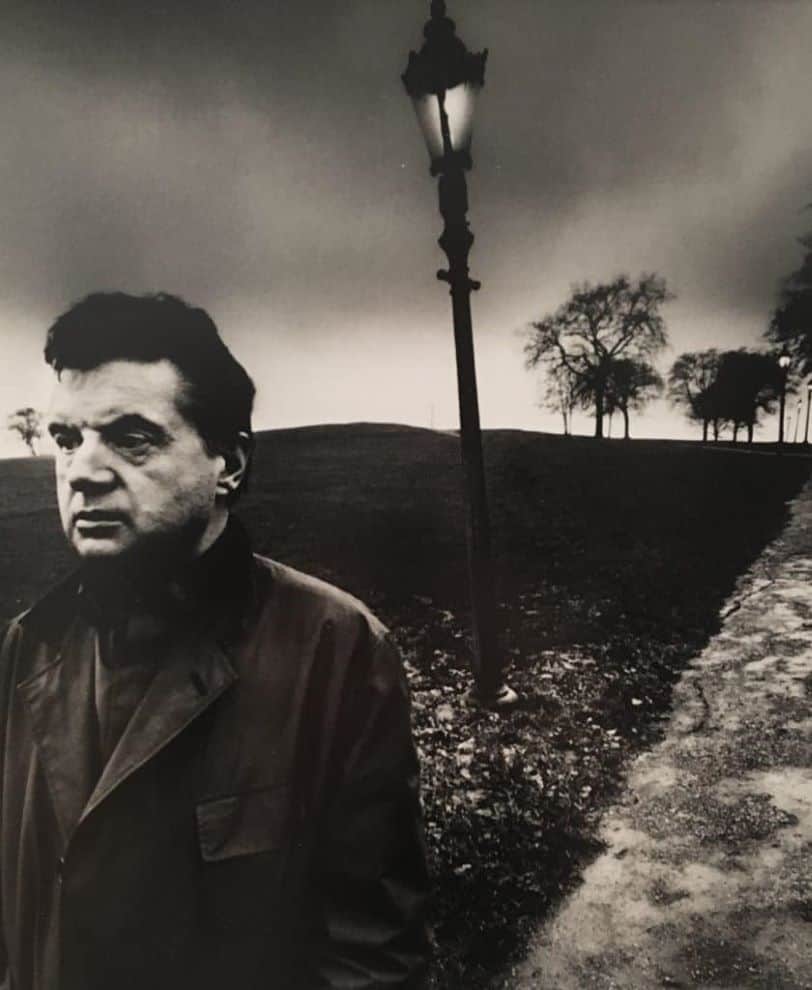

Francis Bacon apparently severely disliked the portrait Brandt took of him, Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London (1963), and yet it became one of his most famous portraits. The photograph captures Bacon with a pensive, tortured expression in a moody, sinister park framed by lit-up lantern posts. Brandt had specifically staged this photograph, planned the location, and considered the exact time of day to take the photograph so that the lanterns would be on, but the sky would not yet be too dark. Brandt had a talent for making such staged photographs seem absolutely spontaneous, as though he had just happened upon Bacon and quickly shot the photograph.

The Artist’s Eye

Another fascinating portrait series is one from the early 1960s, when Brandt photographed only the right or left eye of famous artists, shot up close. He wanted to show the eyes of the artists that were changing the way we look at the world. Among them were Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore, Jean Arp, Georges Braque, Antoni Tàpies, Max Ernst, Jean Dubuffet and Victor Vasarely. Seeing these photographs hanging together, it’s a fascinating experience trying to figure out which eye could belong to which artist. We are shown the artists’ gaze, and can therefore catch a glimpse of how they look at the world and represented reality in their art, or produced a type of reality that did not refer to anything familiar.

Landscapes

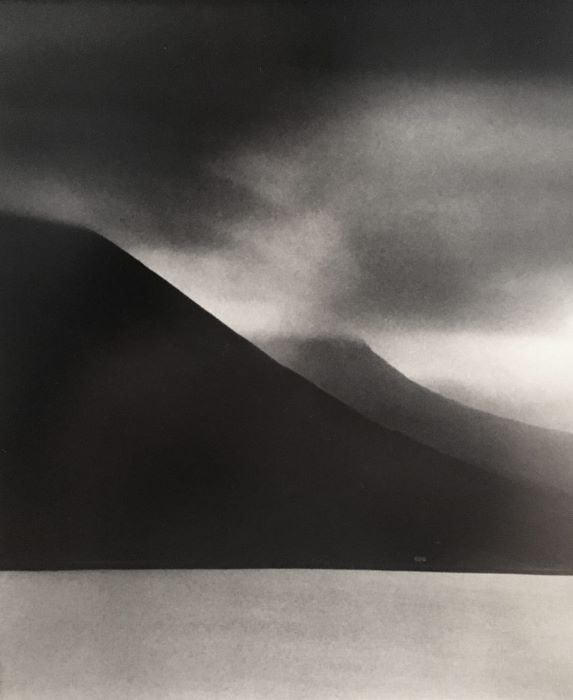

In his landscape photography, Brandt aimed at capturing the very essence of a place in a single image. Painting and literature were important elements in his concept of the landscape. For example, in 1945, he repeatedly photographed Top Withens in West Riding, Yorkshire, the farm that is said to have inspired Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. In another photo-essay, he published a series of eight photographs on Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, associating the locations with one of Hardy’s tragic heroines, Tess of the D’Urbevilles.

In his urban landscapes, Brandt often depicted asymmetrical architecture and streets, steep pavements, sharp ramps, and dark and melancholic scenes. In his nature landscapes, themes such as fate and death shone through, always with a great sense of drama and surrender to the inevitable force of nature and time.

Nudes

Some of Brandt’s most creative work can be found in his nudes, which he started exploring in the 1940s. It is here that the photographer truly found a special touch composing the images, progressively creating photographs of nudes that became so abstract, fragmented, and formally ambiguous that they hardly seemed like human figures anymore and blend in or contrast with the environment in the most surprising ways. Brandt worked with professional figure models, fashion models, and friends or family to produce his nude photographs. He started photographing indoor nudes in 1944, envisaging them as women of the shadows in the vein of Hitchcock movies and film noirs. These nudes are as reserved and difficult to read as Brandt’s portraits of well-known artists. Again, there is a whole hidden layer beneath the surface.

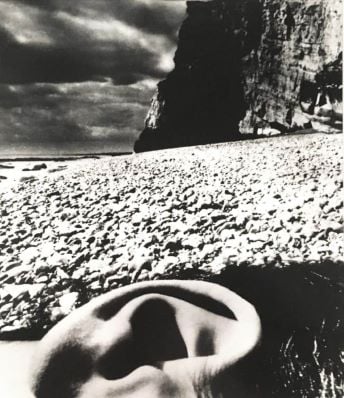

Perspective of Nudes

In the 1950s, Brandt began working on a large series of nudes that constitutes Perspective of Nudes, photographed at coastal sites in Normandy and Sussex. These were fragmented nudes, as he started photographing stones on the beaches and parts of the female body up close, creating an interplay of round shapes and at times even begging the question of which is which. These images make reference to the biomorphic sculptures of Henry Moore, whose portrait Brandt had taken several times. In these nude photographs, Brandt was innovative in his use of camera technology and his focus on form over the sexualization of his female models.

Brandt’s nudes of the 1970s are again vastly different from those of the 1940s and 1950s. The alienation and anger of the artist shine through here, as he started feeling more and more removed from the world in which he lived.

“I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants.”

Bill Brandt

Everything is Permitted in the Darkroom

Brandt had mastered a wide range of darkroom techniques such as blow-up, enlarging, and the use of brushes, scrapers, and other tools. To him, working in the darkroom was essential to make sure he controlled the final image. In 1948, he wrote: “I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants.”

Brandt felt that everything was permitted in the darkroom. He loved working on his prints, and combined negatives to create his perfectly desired image, or would retouch or rework certain images to add something to the image to create a better composition, balance, or more dramatic experience. For example, the dramatic photograph mentioned earlier of Top Withens (1944/45), the farmhouse that inspired Wuthering Heights, was created by combining the dark storm clouds from a negative of a photograph he took in February 1945 after a hail storm with the negative of a photograph he took in November 1944 at the same location. When the painter David Hockney discovered that his favorite Bill Brandt photograph had been composed like this, he was deeply disappointed. Many others also disapproved of Brandt’s darkroom approaches, which were completely opposed to the working ethics and practice of his famous contemporary Henri Cartier-Bresson, who believed that the photographer should not be allowed to manipulate reality with his pictures. But Brandt was a true artist, who was determined that each photograph would end up just as he had imagined the image. In his famous portrait of Francis Bacon, Brandt even added one lonely lantern post at the top of the hill, in order to create the perfect composition in the image. That lantern post was not present on the negative, and Brandt added it on all the prints he made.

For Brandt, his art always stemmed from a place of intuition, dreaming, sensation, and imagination. In working from these points of departure, he may have captured the reality of the human experience in a more truthful way than had he relied solely on photographing the exact moment, without preparing his scenes or allowing himself the creative freedom to rework the images afterward.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more on Artland Magazine

Learn more about Surrealism

Artland Spotlight On: Black and White Street Photography

Cursed Images: A Short History of The Uncanny

Other relevant sources:

Have a look at FOAM, the Amsterdam Photography Museum, for more on Bill Brandt

Explore a selection of works for sale by Bill Brandt

Wondering where to start?