Articles and Features

From Millais to Dalì: Celebrated Artists Who Found Inspiration in Poetry and Literature

By Shira Wolfe

“There, on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds, clamb’ring to hang, an envious sliver broke. When down her weedy trophies and herself fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide, and mermaid-like awhile, they bore her up. Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes, as one incapable of her own distress, or like a creature native and endued unto that element. But long it could not be till that her garments, heavy with their drink, pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay to muddy death.”

Gertrude’s description of Ophelia’s death, Hamlet, Act 4, Scene 7, Lines 147-158a

Artists, writers and poets have inspired each other for centuries. Some of the most famous works of art exist thanks to works of literature and poetry, and each artist approaches topics taken from literature in a completely different and unique way. Here are 5 artworks that would not have existed had it not been for the great writers and poets throughout history.

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851-52

The Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais’s Ophelia is arguably the most famous depiction of a scene from a Shakespeare play. Millais portrayed Ophelia, the tragic heroine in Hamlet, floating in the river right before she drowns to death. Ophelia’s death is considered one of the most poetically written death scenes in literature and has inspired many artists to paint her, but Millais’s version is particularly beloved due to its attention to detail and the beauty of Ophelia and her natural surroundings. The model for Ophelia was the 19-year-old Elizabeth Siddal, who was also an artist and frequently modelled for the artists in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Millais requested her to lie fully clothed in a bathtub in his London studio in order to get the image of Ophelia in the water just right.

Pablo Picasso, Don Quixote, 1955

Marking the 350th anniversary of the first part of the Miguel de Cervantes novel Don Quixote, published in 1605, Pablo Picasso created a sketch of literature’s greatest hero, a hidalgo from La Mancha who decides to become a knight-errant under the name of Don Quixote, and his sidekick Sancho Panza, in 1955. The sketch was featured on the cover of the August 18-24 issue of the French journal Les Lettres Françaises. Remarkably, the sketch differs strongly from Picasso’s iconic style in his Blue, Rose and Cubist periods. Instead, he here favoured a simple approach of bold black lines full of movement, set against a white background. The drawing shows Don Quixote on his horse and his sidekick on his donkey, with a simple sun, some windmills, and a grassy knoll as the only other elements in the sketch.

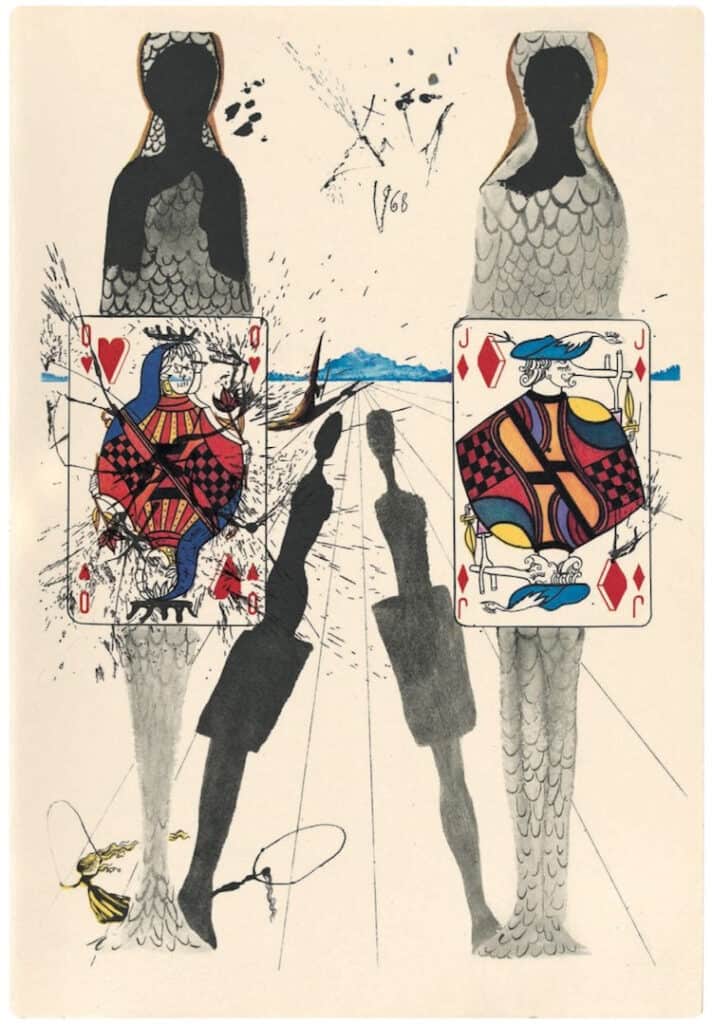

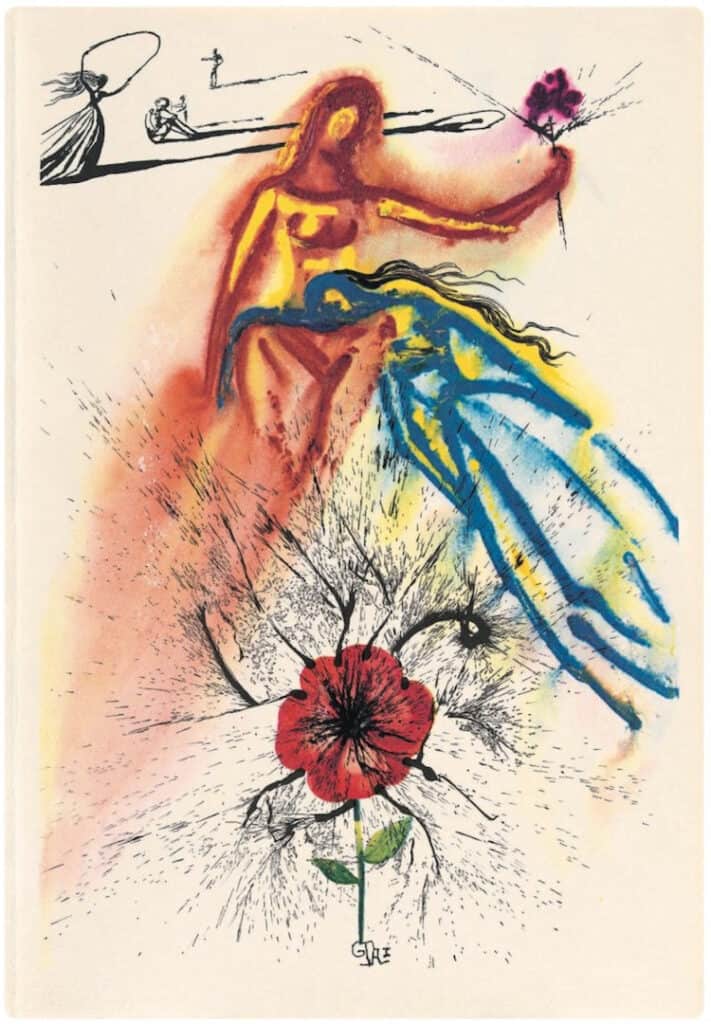

Salvador Dalí’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland, 1969

In 1969, Salvador Dalí was commissioned to illustrate a limited edition of Lewis Carroll’s literature masterpiece Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A match made in heaven, Dalí created 12 beautifully colourful heliogravures for each chapter of the surreal story of Alice in Wonderland, as well as a four-colour etching for the cover. 2700 copies were printed and each original etching was signed by Dalí. These etchings appear softer and freer in their expression compared to Dalí’s usual, meticulously executed, hyperrealist surreal paintings. Still, the artworks are unmistakably Dalí, with his psychedelic imagination and some of his most beloved imagery, like the melting clock, finding a place in the etchings.

“Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold…”

William Carlos Williams, The Great Figure

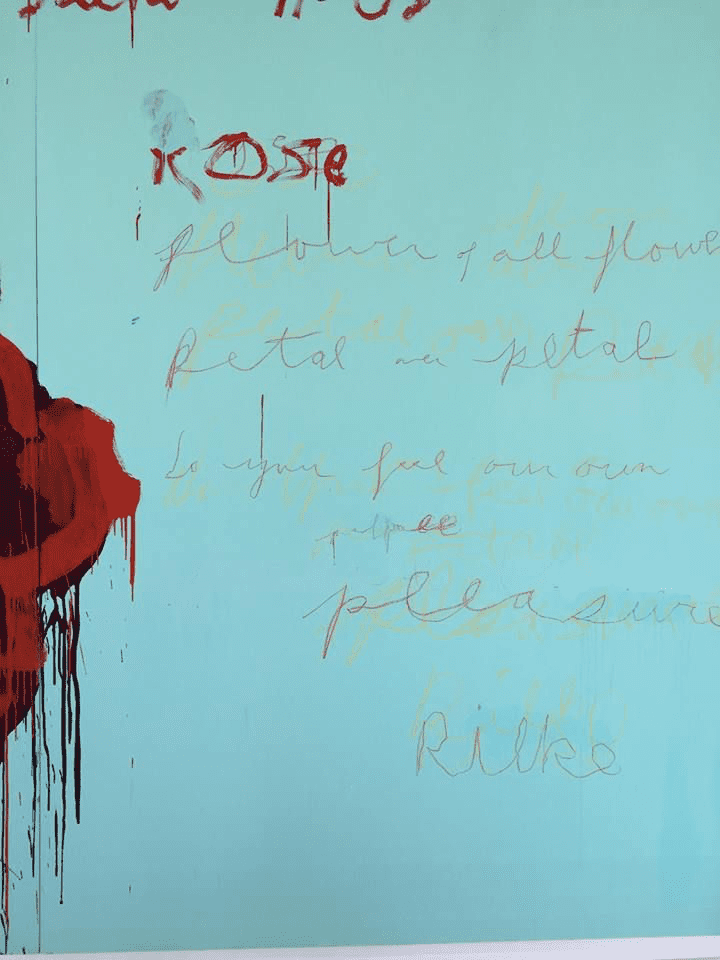

Cy Twombly’s poetry in painting

Cy Twombly had a remarkable way of infusing his paintings with his favourite poetry and literary influences. He left New York and settled in Italy in 1957, where he created artworks inspired by ancient mythology, poetry and philosophy. At times, Twombly would create pieces that consisted of the scribbled names of poets, writers and philosophers whose writing he admired. Take, for example, his works Five Greek Poets and a Philosopher (1978), a set of lithographs with the names Homer, Sappho, Pindar, Callimachus, Theocritus and Plato inscribed on each piece of paper. Then there is the Virgil series (1963), where Twombly explores the name of the great Roman poet. In other artworks, such as Untitled (To Sappho) (1976) and Analysis of the Rose as Sentimental Despair (1985), he actually quotes lines from poems by poets including Rainer Maria Rilke, Sappho, Charles Baudelaire, Giacomo Leopardi and Rumi.

Charles Demuth, I saw the figure 5 in gold, 1928

Charles Demuth, an artist associated with Precisionism and Art Deco, made eight abstract portraits between 1924 and 1929, all tributes to modern American artists, writers and performers. In 1928, he made a portrait of his friend, the poet William Carlos Williams, and used imagery from Williams’s poem The Great Figure. The poem goes as follows: “Among the rain / and lights / I saw the figure 5 / in gold / on a red / firetruck / moving / tense / unheeded / to gong clangs / siren howls / and wheels rumbling / through the dark city”

Williams evokes the sights and sounds of a fire truck driving through the streets, and Demuth’s abstracted, colourful images inspired by the poem together create a vibrant, bold energy and a fantastic portrait of a poet through the images of his own poem.

Relevant sources to learn more

The Paris Review: Reading Cy Twombly

Read more about Cy Twombly’s poetry and painting here.

Read about Precisionism, the art movement Charles Demuth aligned himself with.

Discover Dalī’s foray into cinema.

See all 12 of Dalí’s etchings for Alice in Wonderland here.