Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938

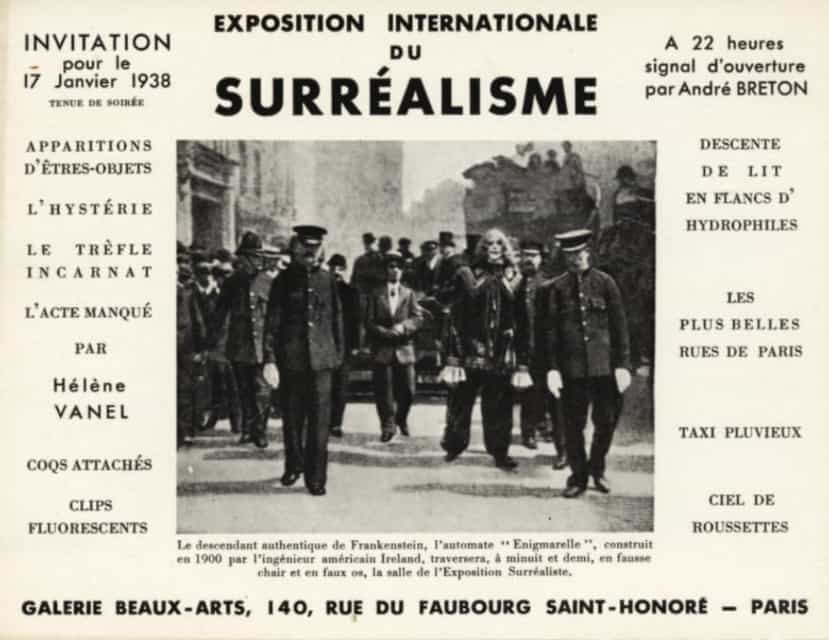

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider the history of art exhibitions themselves? Landmark shows of the modern and contemporary period have impacted and shaped the course of art history, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices. This week, we delve into the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme. Many Surrealist group exhibitions had preceded it, many would follow all over the world – from Tokyo to Mexico City; however, the one that took place at Galérie Beaux-Arts in Paris that year, was without a doubt the key exposition of the genre. Not only did it represent the ultimate manifestation of the surrealist movement in the seminal interwar period, but also it anticipated the innovative concept of art show as an immersive experience by almost three decades.

The background

Few other artistic movements were as cross-sectorial and inclusive as Surrealism. Not defined by any specific medium or style, it spanned all those disciplines capable of manifesting the uncanny side of reality, ranging from Visual Arts to Music, Theatre, and Cinema. It entailed a philosophical approach instead, as – in artist Joyce Mansour’s words – “It is not the technique of painting that is surrealist, it’s the painter and the painter’s vision of life”. Nonetheless, when early forms of Surrealism originated in the late 1910s, it was essentially a literary movement. Surrealist poets were hesitant about engaging in art production as, in their view, the mechanical act of creating art – whether it was drawing, painting, or sculpting – impeded the spontaneous expression of the unconscious. It was not until the mid-1920s that the prime theorist of Surrealism André Breton, in his seminal Surrealism and Painting, reconsidered the potential of visual arts as a means to unlock the power of the psyche and create absurd imagery, partly humorous and partly ominous, a manifestation of contradictions in everyday life.

Based on his renewed convictions, Breton opened a designated gallery in Paris, the Galerie Surréaliste, and also decided to set up a series of collective exhibitions starting with the first one at Pierre Loeb’s gallery in 1925. It featured pieces by both Surrealist members and other, somewhat related, artists such as Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, and Marcel Duchamp, considered to be kindred to surrealist artistic aspirations because of the imaginative and provocative qualities of their work.

Other shows followed as Surrealism’s fame and influence grew internationally. Another group exhibition took place in Paris in 1928, titled Surréalisme, existe-t-il? (‘Does Surrealism exist?’); three years later, the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, hosted the first American edition, while, in 1936, it was the turn of the New Burlington Galleries in London.

As provocative and eclectic as these shows were in terms of content, they adopted rather traditional modes of display. But the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938 would soon upset the conventional categories of exhibition with an unprecedented and groundbreaking surrealist environment.

The main characters

To organise the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938, Breton, along with the poet Paul Éluard surrounded themselves with the leading figures of the movement, a dream team of artists and intellectuals of various geographical origins but all active in Paris at the time.

They enlisted Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst as technical advisers, while Man Ray was in charge of lighting, and Wolfgang Paalen was responsible for exhibition design as well as for “water and foliage” – a detail that suggests the whimsical and audacious quality of the show.

The duo also recruited Marcel Duchamp, whose contribution proved to be fundamental. Though the artist did not officially belong to the movement because of his general resistance to group affiliations, he joined the team in the role that, today, would probably belong to an art director. He also acted as an important mediator, forming a crucial buffer between Breton and Éluard who often held contrasting positions.

The show

The 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition took place at Galérie Beaux-Arts, from January 17 to February 24. If you envision visitors walking peacefully, absorbed in admiring artworks hanging plainly on white walls, you are not on the right track.

On the contrary, they were encouraged to follow a dreamlike path – at times amusing, at times disturbing – in an incessantly stimulating environment.

A typical visit began in the forecourt where Dalí’s Taxi Pluvieux (‘Rain Cab’) was installed: an old vehicle covered in ivy with a system of pipes creating a continuous downpour in the interior. Two mannequins, a man with a shark-head and a woman dressed in an evening gown, sat inside surrounded by lettuce and chicory as well as live snails crawling around.

Leading from the lobby was the Plus belles rues de Paris (‘The most beautiful streets of Paris’), the first of two main sections. It was a dark, long corridor marked by street signs, referring both to actual Parisian streets and surrealistic symbols and obsessions such as Rue de la Transfusion-du-Sang (‘Blood Transfusion Street’) and Rue Cerise (‘Cherry Street’).

The hallway was also lined by sixteen mannequins rented from a French manufacturer, each provocatively costumed by a different artist. The one designed by Paalen was covered in moss and fungi and had a bat on her head. Man Ray set a figure with big glass tears and pitch pipes on the head; while the one that drew the greatest attention was Masson’s Girl in a black gag with a pansy mouth; its head in a wicker birdcage, and its mouth covered with a velvet fabric decorated with a pansy.

The corridor led to the main hall, a central space that resembled a grotto. The floor was covered in a carpet of sand and leaves, whereas 1200 coal bags hung from the ceiling – they were stuffed with newspapers but designed to leak coal dust on the visitors underneath. Four beds positioned in the corners explicitly invited to abandon reality and symbolically enter the space of dreams, while in the middle stood a lit iron brazier for visitors to huddle up around it like tunnellers of the unconscious. An actual pond, complete with water-lilies and reeds, was located a little further on.

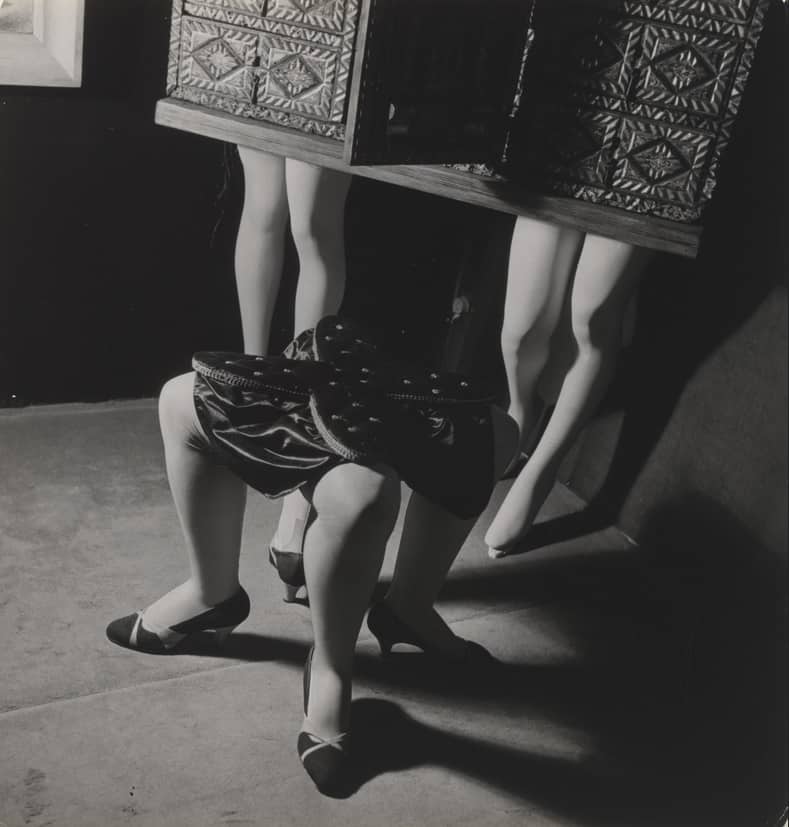

Paintings, collages, and photographs were hanging on walls and revolving doors, but also quirky Surrealist objects – such as Seligmann’s Ultra-furniture (a stool made of four female legs) and Breakfast in Fur by Meret Oppenheim – were displayed. Altogether, the show featured 229 works by 60 artists. Besides the organisers and their exceptional team, works by Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, and René Magritte were also showcased, as well as by Joan Miró and Yves Tanguy.

As the exhibition was almost entirely plunged in darkness, the public was provided with flashlights; an expedient that enhanced the sense of disorientation and surprise. To further increase the immersive character of the environment, coffee was roasted to emanate “perfumes of Brazil”, and a soundtrack of cries and laughter was played through a loudspeaker along with a German military march.

If the elaborate set-up was exaggerated enough, its vernissage was even more dramatic.

The opening was scheduled at 10 pm, and a crowd in mandatory evening dress turned up to attend the supposed show of a sky full of flying dogs and Enigmarelle, a fake humanoid automaton, as the invitation card announced. As an alternative, they witnessed a dance performance by Hélène Vanel titled ‘The Unconsummated Act’; the artist tore her own clothes, dived into the pond, and simulated a hysterical attack in one of the beds.

Recognition and legacy

The International Surrealist Exhibition proved to be a success, attracting thousands of visitors – 3000 only at the vernissage. However, the show did not fully achieve its aim to shock and amuse at the same time. The audience had become accustomed to Surrealist eccentricity and provocative attitude such that, after the initial excitement, they found the works somewhat ridiculed rather than amusing, and forcefully excessive rather than shocking.

Two other aspects seemed to draw the most attention instead. On the one hand, the frivolous character of the exhibition stood out, as it mainly attracted the Parisian cultural elite and international high society. Visitors reported that “the flashlights were pointed at the faces of the people rather than at the artworks themselves. As at every overcrowded vernissage, everyone wanted to know who else was around”.

On the other hand, critics pointed out how the show reflected the anxiety surrounding another World War lurking on the horizon, as if an immersive omen was pervading the atmosphere. In the newspaper La Lumière, Marie-Louise Fermet reported a “feeling of unease, of claustrophobia and the premonition of a terrible calamity”.

Surprisingly, the aspects of the 1938 Surrealist exhibition today considered as the most innovative, namely its conception as a total, immersive experience rather than simply a showcase for artworks as well as the transformation of the space of the exhibition into a creative production in its own right, seemed to go rather unnoticed at the time. However, the abandonment of the traditional display format in favour of multi-sensory installations would exert an enormous impact on the following experimentations, especially in the advent of early conceptual, Fluxus and performance happenings in the1960s.

Though other Surrealist exhibitions took place in the years before 1967, the Surrealist movement in Europe as an organised body dissolved with the onset of World War II. The 1938 Surrealist exhibition represented its final, grandiose manifestation, an apogee of ideas, commitment and contribution by almost all of the seminal protagonists. Since many Surrealist members flee Europe to escape Nazi persecution, the movement’s radical ideas found renewal across the ocean, influencing numerous important later developments, ranging from Abstract Expressionism to Neo-Dada and Fluxus.

Relevant sources to learn more

Documentation of the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition by Roger Schall – MoMA

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

The Salon Des Refusés

The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’

The Armory Show

Nazi Censorship And The ‘Degenerate Art’ Exhibition of 1937