Articles and Features

A Mellowing Dictator.

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jonathan Meese

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Volume 14

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in a recent standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

50-year-old German painter Jonathan Meese just closed his second show at David Nolan Gallery in New York. The show is making noise and generating chatter; images of it have been wafting around as pollen of the internet. The reviews, and the comment sections, are largely sympathetic. It is a mellow, warm feeling, and it is new for this artist. I wondered if it was because art viewing and gallery hopping has come back for good, with starved people beyond thankful to see new art in real life for the first time in 13 months. I wondered if it was because Nolan’s new townhouse space, a swanky uptown mood one block away from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a jewel, and that art glitters inside it. Whatever it is, people are presently positive about Meese, savouring the new work like wine.

Courtesy of David Nolan Gallery and the artist.

The positivity is a shock to the system since, for more than 20 years, Meese has been a paragon of aggressive animus, as divisive and provocative as any artist on the global scene. In paintings, sculpture, installations and performance, Meese has long employed the iconography and methodology of fascism. He has long been a wild zealot for ‘The Dictatorship of Art’, a personal philosophy and all-encompassing worldview asserting art’s total supremacy above all things, including taste. If you’re lucky, you might show up to a Jonathan Meese lecture-performance and see the artist transform the procedural banality of the artist’s talk into a blaring, rhythmic rant about abandoning history and propriety in service of art, with lots of Hitler. At one such talk, in the booming Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern in 2006, he was heckled from the crowd by the eminent artist Mark Wallinger. This moment, remembered only by the people who were there, is as unusual as it gets in British art society. Meese gets under people’s skin.

Meese has an ideology that damns ideology. Art first, above all, with zero compromise. Concessions are not made to the viewer. His paintings and collages, frenzied and filled with text, are scratchy, hard and fast. They owe an aesthetic debt to German Neo-Expressionism of the 1980s, to the mania of Art Brut, to Action Painting. Their titles, in capital letters, are word salad. They can feel like a voice shouting at you, then other voices shouting over the top, a cacophony. Every aspect of the work is intense, and this intensity extends to Meese’s self-presentation: the artist showcases looks that touch upon football hooligan, Aleister Crowley chaos cult leader, dark-hippie LSD guy or sadistic military doctor, a little edgy every time. It is all part of the package. His work and his persona might reasonably be called unpleasant. There is a consensus view that his work and persona is, at times, distasteful.

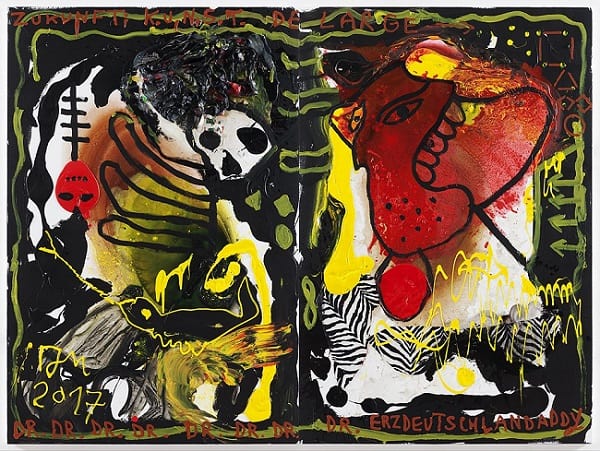

Something’s changed. The Nolan show is mostly modest in scale, with framed small works on paper, tabletop sculptures and a few trophy canvases. The largest painting in the show, KUNST: DER WELTRAUMFAHRERZ DE MEESI!, is a two-metre tall self-portrait, recognisable as such by the long black hair that swoops over the figure’s forehead. The man has devil horns, a proboscis from the side of his head that reads as a periscope or snail’s tentacled eye, a button nose with whiskers, like a cat, and a large, impasto iron cross inscribed in red modelling paste by his heart. The cross — an ancient and problematic German symbol of dominion spanning the medieval Teutonic era through the Third Reich — is red meat for Meese, the sort of autopilot jump-scare that the artist cannot help but create, but the image is otherwise measured and spacious. The composition isn’t choked. It flows around the canvas, the fragments of text in black, red and white framing the central figure elegantly. It is messy but unviolent, crude but hard-won. It looks like he has considered, rather than attacked the canvas. It breathes, approaching an improbable harmony. The proof is in the cross, which does not trigger or provoke. It settles into the work as a formal element, uninflected by the trauma of history. This man is not someone to fear.

Several of the smaller portraits on paper depict Meese as characters of uplifting power. He is HORUSMEESE in one, a version of the Egyptian god of the heavens, radiant in wet yellow and red acrylic paint mushing together. He is made of the sun. SAMURAIMEESE is a windswept warrior, perched and regal. The idols of power Meese inhabits in these portraits are human, fallible, strong but imperfect. Horus has a scar on his cheek. The samurai’s hand is a circle with lines flying out of it — a warrior whose tool appears to be depicted by a child.

Considered as a whole, Meese’s totalitarianism appears to have sublimated beyond aggression. It is worth noting that all the work in this exhibition was made over the past 12 months, when global society closed down. Left with himself, the intolerance Meese preached in the name of freedom may have worn out its usefulness. Breaking away from the shadows of fascism that had haunted his practice for 20 years, Meese now seems to be searching for new forms of power. Radicalism without an audience is impotent, and Meese’s softening surely represents a need for a more durable form of strength through which the artist may live his life.

We may return to the initial question of why Meese appears so palatable at this moment, after decades as an acquired taste or anathema, depending on who you ask. I believe it’s bigger than the novelty of being back on the gallery circuit, the rush of visiting contemporary spaces with the aura of churches. I believe, ultimately, that this exhibition transcends by providing a lesson of art’s ability — for makers and viewers alike — to move us forward. In this work we can feel evolution as it happens, through an adaptation to life’s challenges and a revision of ideals. The radical inches a little way toward the centre in order to live a happier existence and give more to the world. May we all start the mysterious next chapter of our lives with a tweak to our habits, a check-in on our behaviour and beliefs. Meese seems in better touch with himself than ever before. It is a pleasure to feel that someone is healthy.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.8 : Palace Intrigue

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.9 : Accepting Alchemy through Bruce Nauman and the global pandemic

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.10 : Working Through A Daze With Dana Schutz

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.11 : Halfway To The Future. Saatchi Yates’ Proposal For Tomorrow’s Art Gallery

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.12 : The Body Won’t Quit. Finding a Way Through 2021

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.13 :Thomas Hirschhorn and Our Life in Ruins