Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: The World Through the Lens of Diane Arbus

By Adam Hencz

“For me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture. And more complicated.”

Diane Arbus

Our Female Iconoclasts series highlights some of the most boundary-breaking works of our time, crafted by women who defied conventions in contemporary art and society in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to the world.

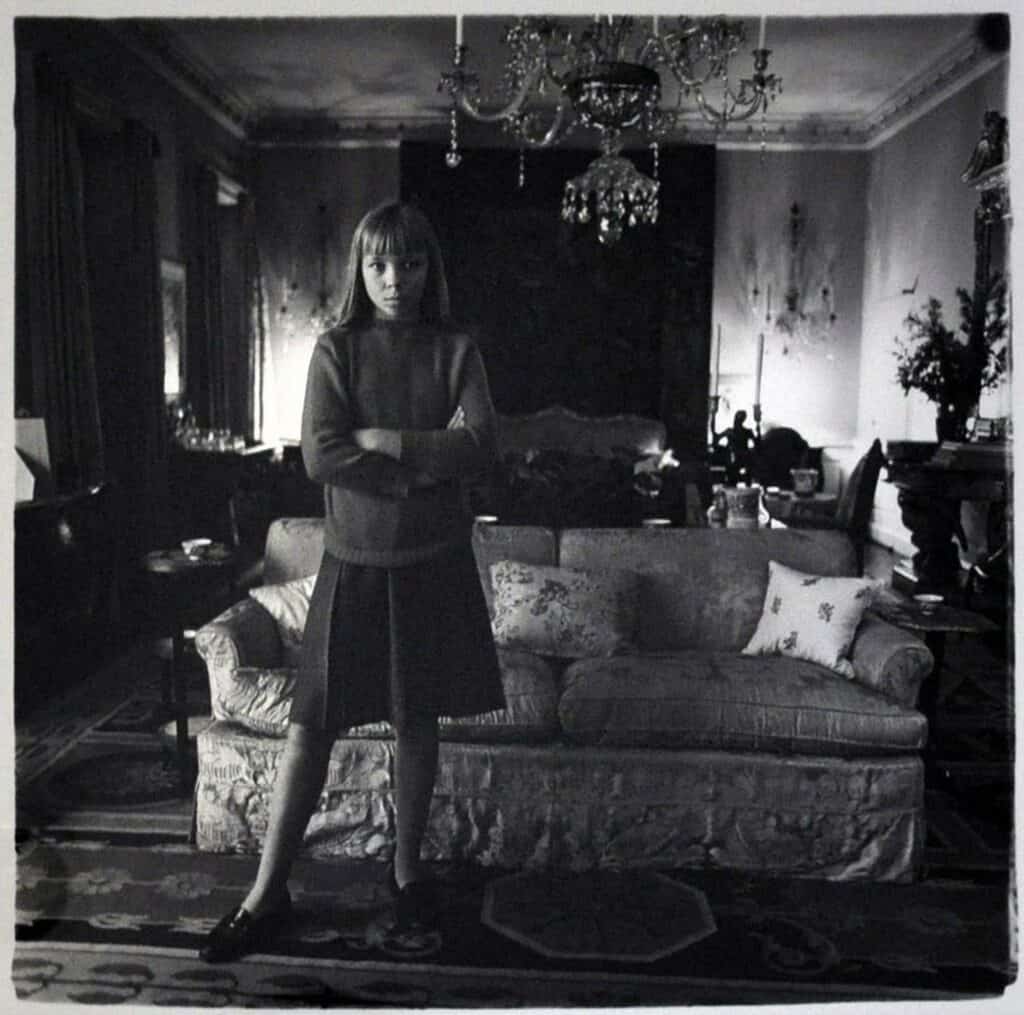

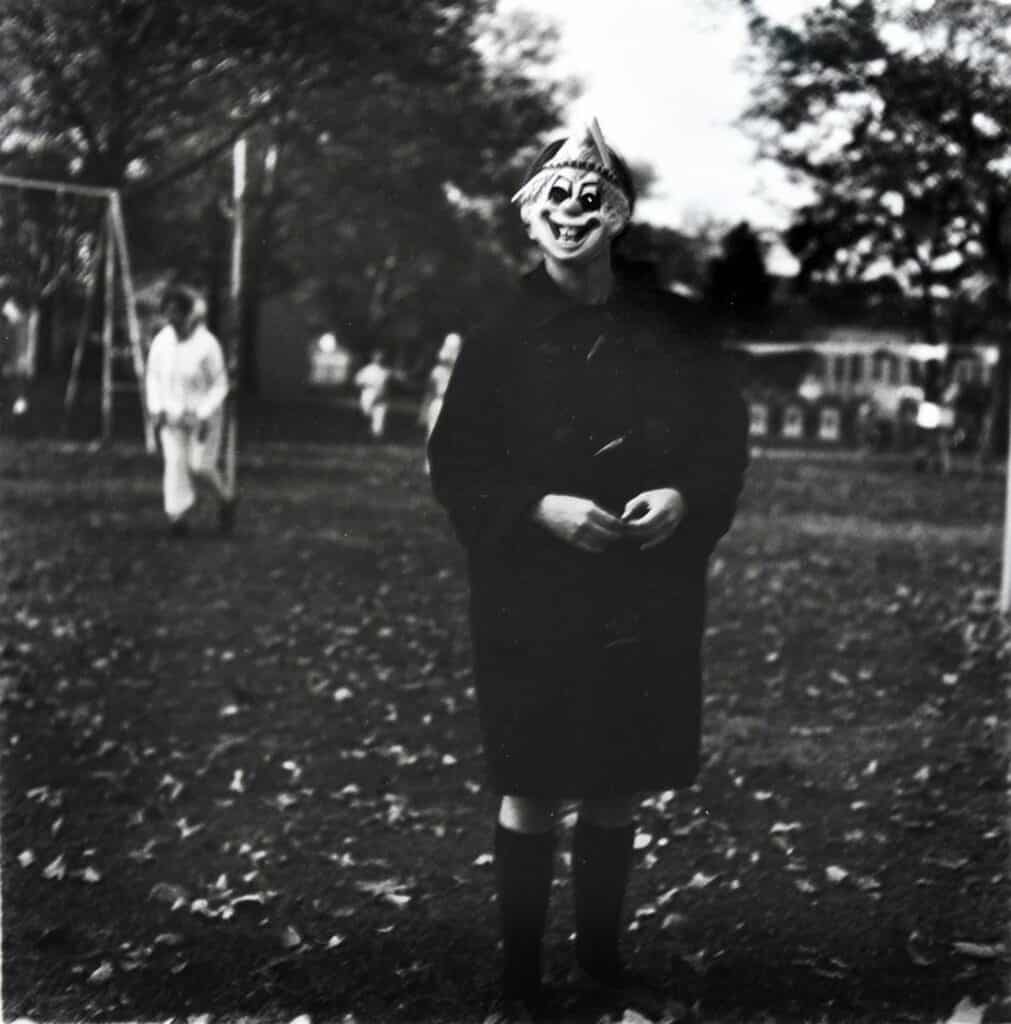

In this edition, we focus on Diane Arbus, one of the most original and influential American photographers of the twentieth century, who became renowned for her eerie black and white images, creating a profoundly personal style of portrait photography. Arbus’s career kicked off as a fashion and advertising photographer, eventually earning assignments from Vogue. Her artistic career has been marked by constant questioning on identity, gender, bodies, and ageing. Her intimate, at times unsettling, but pure photographs of marginalized groups such as little people, transvestites, and giants, along with her unique representation of a wide range of subjects including strippers, carnival performers, nudists, elderly couples, and middle-class families brought her recognition already in her lifetime. Her pioneering photographs were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art for the New Documents show in 1967 alongside young photographers Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand.

Diane Arbus, Radical Photographer

Arbus was born Diane Nemerov in 1923, in New York City into a wealthy, entrepreneurial and talented family, who owned a successful fur company named Russeks, in a high-end Fifth Avenue department store. Her father encouraged her to become a painter, and she studied art in high school. At the age of 14, she fell in love with Allan Arbus, the 19-year-old nephew of one of her father’s business partners, whom she married after graduation. Her complicated relationship with Allan Arbus would interweave her whole life. From early on, the Diane and Allan were both fascinated by photography. The couple transformed the bathroom of their Manhattan apartment into a darkroom, while Diane’s father started giving them fashion photography assignemnts for the company’s advertisements. After the Second World War, the couple began working together professionally on fashion and advertising. Diane took the role of the creative director, while Allan shot the images. The couple’s hard work and collaboration soon paid off, as they were commissioned to shoot for high-fashion magazines such as Seventeen, Glamour, and Vogue.

Feeling frustrated by the limitations and stresses of fashion work, in 1956 Diane quit the couple’s business in order to make photographs on her own and began numbering her negatives. She started shooting with a 35mm Nikon later switching to medium format, wandering the streets of New York City and meeting her subjects largely, though not always, by chance. Fascinated by risk-taking, Diane had embraced the city’s life-on-the-edge attitudes about money, social status, and sexual freedom. Her excited appreciation of whoever struck her as extraordinary allowed her to gain entry to a female impersonator’s boudoir, a dwarf’s hotel room, and countless other places that would have been closed to a less persistent, less determined photographer. Once she obtained permission to take pictures, she might spend hours, even days shooting the unique milieux a very few had experienced before.

In 1959, the couple separated, but their lives remained closely intertwined. Despite receiving notable grants such as the Guggenheim Foundation’s fellowship and achieving some fine-art world recognition. Arbus struggled to support herself through her work and the lack of money was a persistent concern. Even after her major breakthrough in 1967, when 32 of her photographs were chosen by MOMA for its New Documents exhibition, Arbus had to rely on other sources of income beyond photography and journalism to sustain herself.

Around this time, another, more personal stress was eating at Diane: a betrayal by Marvin Israel, with whom she had been seriously involved for about ten years. Diane had always been attracted to men who could not devote themselves entirely to her, justifying the attachment as something that fed her creative life. However, at that stage, came a fatal breaking point. Disillusioned and struggling with depression, Diane Arbus committed suicide on July 26, 1971, at the age of 48.

“They are the proof that something was there and no longer is. Like a stain. And the stillness of them is boggling. You can turn away but when you come back they’ll still be there looking at you.”

Diane Arbus, 1971

Where to find Diane Arbus’ works?

Arbus’s photographs can be found in the collections of numerous institutions around the world and have been exhibited and examined extensively. A year after her death, her work was selected for inclusion in the Venice Biennale, the first time any photographer had been so honoured. In 2007, The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired the artist’s complete archive from the Estate of Diane Arbus. The collection includes hundreds of early and unique photographs by Arbus. Most recently, in 2016, The Met Breuer hosted in the beginning, a landmark exhibition of Arbus’s work focusing on never-before-seen early photographs from the first seven years of her career, from 1956 to 1962. The exhibition traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Malba, Buenos Aires; and Hayward Gallery, London. The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were part of the Museum’s Diane Arbus Archive from the artist’s daughters, Doon Arbus and Amy Arbus. In 2018, the Smithsonian American Art Museum presented Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs, an exhibition exclusively featuring a series of photographs from the only one portfolio completed and sold by Arbus that is publicly held.

For previous editions of our Female Iconoclasts series, see:

Frida Kahlo

Marina Abramović

Lousie Bourgeois

Sophie Calle

Marlene Dumas

Yayoi Kusama

Niki de Saint Phalle

Wondering where to start?