Articles and Features

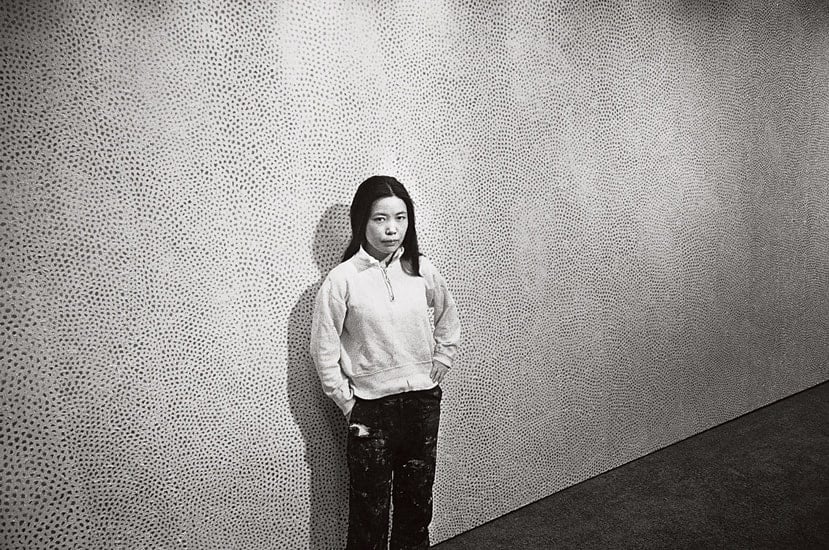

Female Iconoclasts: Yayoi Kusama

By Shira Wolfe

“Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the cosmos. Polka dots are a way to infinity. When we obliterate nature and our bodies with polka dots, we become part of the unity of our environment.”

Yayoi Kusama

Who is Yayoi Kusama?

In our article series “Female Iconoclasts,” we celebrate women artists who are among the most innovative creators of our time; women who sometimes defied prevailing social conventions in order to pursue their passion in order to contribute their unique vision to society. Here we look at Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, also known as the ‘Princess of Polka Dots’ and the creator of the magnificent Infinity Rooms.

Today, she is one of the most popular contemporary artists whose bright red wig, vibrant polka dot works and interactive mirrored infinity rooms are like candy to the world of Instagram art lovers. Her importance as a figure in both Minimalism and Pop Art contexts is finally recognised unanimously around the world, and she is no longer hidden in the shadows of her male peers.

Biography of Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi Kusama’s First Moves in Art

Yayoi Kusama was born in Matsumato, Japan in 1929, and grew up in an unhappy family with a philandering father and a mother who would take out all her rage on her young daughter. Kusama started making art from an early age, but this was strongly discouraged by her family and her mother even went as far as to destroy her paintings and drawings. One day, while she was drawing among a field of flowers, she suffered the first of a series of hallucinations that would come to haunt her all her life. The flowers started to crowd in on her and speak to her, and she was so terrified she couldn’t stop shaking. For Kusama, drawing became her way of making sense of these hallucinations. She explains: “Whenever things like this happened I would hurry back home and draw what I had seen in my sketchbook… recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes.” For years, she produced large amounts of artworks every day, and when she encountered the work of Georgia O’Keeffe in a local bookshop, she started writing to the artist in New Mexico asking for her advice about coming to the United States and making one’s way as an artist in New York. She desperately sought to break free from the constraints of her society, longing for what she perceived as the artistic freedom of New York.

Yayoi Kusama Moves to New York

Kusama arrived in New York in 1958. She was 27 years old and only brought with her a few hundred dollars, 60 silk kimonos and some drawings – the idea was that she would survive by selling her drawings, or the kimonos, or both. It was no easy task trying to assimilate into the New York art world, and anecdotes from this time include her dragging a canvas larger than herself 40 blocks across town to submit it to the Whitney Annual, to no avail. Yet Kusama found her way. At some point, she lived in the same apartment block as Donald Judd and the two artists became friends. She sold Judd and Frank Stella the first of her iconic Infinity Net paintings in 1962 for just $75 apiece. Today, these go for over $7 million apiece. The Infinity Net paintings were Kusama’s breakthrough paintings, in which finely formed nets or loops made from a repetitive singular gesture stretch across the surface of her paintings referencing the connectivity of the cosmos, or on a micro level, cells, or atoms.

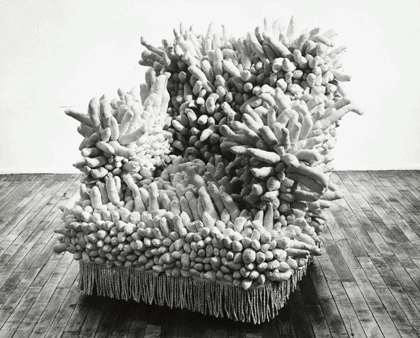

In 1962, Kusama began to make various objects and cover them in white phallic forms made from stuffed fabric. Working with this symbolism was Kusama’s personal approach to therapy, meant to heal feelings of disgust towards sex that she had carried with her since childhood. She shared these feelings about sex with Joseph Cornell, the famously reclusive collage artist known for his intricate collage and assemblage boxes. The two became close friends and lovers, albeit without the sexual element, and their partnership was an important source of inspiration for both artists.

In and Out of Focus

During the ‘60s, there were moments when Kusama was almost as notorious as artists like Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. For one performance piece, she strutted through rough New York City neighbourhoods dressed in full traditional Japanese costume – making sure she was both understood as an outsider and also as an unforgettable and iconic character. In 1965, a major breakthrough came when she produced Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. She used mirrors to transform the repetition of her earlier works into a live, perpetual experience. Kusama then took part in the 33rd Venice Biennale (1966), creating a lake of 1500 reflective balls multiplying the viewers’ faces, which she called Narcissus Garden. She proceeded to sell the balls for $2 apiece, promoting it as “your narcissism for sale” until the Biennale forced her to stop the performance. By the end of the ‘60s, Kusama was engaged in all kinds of happenings and performances around New York in which she would paint naked people with polka dots.

Yet despite these successes, her name and work somehow became eclipsed in the early ‘70s, in part perhaps due to the backlash against the wild ‘60s excesses, and in part due to the fact that many of Kusama’s ideas were appropriated by male artists around her. People like Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol used ideas and concepts developed by Kusama (in Oldenburg’s case the “soft sculpture,” in Warhol’s case the repetitive wallpaper prints) and achieved fame far more readily. This deeply affected Kusama, who started to become overlooked in New York, and after the death of Joseph Cornell in 1972, she returned to Japan. Her hallucinations and panic attacks started to return again, and in 1977, Kusama admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo.

“I am very lonely being an artist, and in my own life. It is almost unbearable, especially when I hear the sound of the tree leaves trembling in a wind storm. When I go up to the rooftop of a high-rise building, I feel an urge to die by jumping from it. My passion for art is what has prevented me from doing that.”

Yayoi Kusama

Life in a Psychiatric Hospital, and Fame

The psychiatric hospital actually provided great relief for Kusama, who found a way to deal with her hallucinations and traumas and work with them more productively in her creative output. She took art therapy courses at the hospital, a healing and nurturing time which she regards as her lifesaver. In an interview, she explains: “I am very lonely being an artist, and in my own life. It is almost unbearable, especially when I hear the sound of the tree leaves trembling in a wind storm. When I go up to the rooftop of a high-rise building, I feel an urge to die by jumping from it. My passion for art is what has prevented me from doing that.”

Kusama never really left the hospital – instead, she used it to create a fascinating life situation that works well for her. Her studio space is across the street from the hospital, so every day she works in the studio, and at night she sleeps in the hospital. She still has her art therapy classes and leads a simple life. All this is even more fascinating when we consider the fact that Kusama has been on a steady rise to fame for the past few decades. In 1993, Kusama was granted the entire Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which she transformed into an impressive mirrored room filled with small pumpkin sculptures. The pumpkin motif, populating Kusama’s hallucinations and visual imagery since her childhood, would come to represent a kind of alter-ego or self-portrait for the artist. In 1998, London’s Victoria Miro Gallery showed one of her Infinity Mirror Rooms, and there were hardly any visitors. By now, the Infinity Mirror Rooms are so popular that museums and galleries often have to enforce time limitations per visitor so that each has a chance to experience the work.

The power of Kusama’s work is that it holds such universal appeal, allowing for crossovers with fashion and design, and connecting to people young and old. But underneath the seemingly simple and fun dotted artworks that have become Kusama’s signature style, there remains a deep well of psychological development and the artist’s search for unity between people and their environment.

Where to find Yayoi Kusama’s work?

The work of Yayoi Kusama is part of prestigious collections across the globe, from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. In 2021, the Gropius Bau in Berlin has devoted the first comprehensive retrospective in Germany to Kusama’s work: A Bouquet of Love I Saw in the Universe, while the New York Botanical Garden is currently housing KUSAMA: Cosmic Nature, a major exhibition inspired by the artist’s lifelong fascination with the natural world.

Relevant sources to learn more

Explore the work of other contemporary artists whose ideas and practices have greatly influenced the times we live in:

Joseph Beuys

Louise Bourgeois

Sophie Calle

Dan Flavin

Guerrilla Girls

Damien Hirst

Jenny Holzer